“Great TV is about cool people doing cool shit.

…

I don’t feel that the mysteries are why people watch TV. Because my bottom-line rule of TV is that it’s cool people doing cool shit every week. That’s it.

Let’s break down that sentence. Cool people doing — doing — cool stuff every week. Not learning cool stuff every week. They need to be active.”

—Glen Mazzara

Sid Meier, Sid Meier’s Memoir:

“Soon after that, Bruce’s feedback took an unexpected turn. It was unfair, he noted, that his bridges kept washing out in floods. I countered that SimCity had included a robust variety of natural disasters, including tornadoes, earthquakes, and non-copyrighted Godzilla-ish monsters who stomped through buildings with abandon. Compared to all that destruction, the occasional bridge washout didn’t seem so ruthless. Besides, flooding was a legitimate concern for rail companies, certainly more so than sea monsters were for city planners.

But Bruce reminded me of one of my own axioms of game design: make sure the player is the one having the fun. “When my bridge is knocked down for no reason,” he said with a placid shrug, “I’m not having fun.”

He was right, of course. It seems like players ought to appreciate the hardships we throw at them — that the whole reason they play is to prove their worth. But it’s not. People play games to feel good about themselves, and random destruction only leads to paranoia and helplessness. Thwarting an enemy’s attack feels worthy, but recovering from an ambush is a relief at best. Unfortunately, the flip side of that imbalance is that the designer feels powerful and clever, which is what makes these unexpected setbacks so tempting to implement. As major plot points, they’re practically universal: your trusted partner steals the treasure; the damsel who begged for help is a double agent; the noble scientist has a secret weapon to wipe out mankind; the princess is in another castle. Or in other words, the player did everything the designer asked of them, and then the rules changed for no reason. A sudden reversal of fortune is only exciting or dramatic when it happens to someone else. When it happens to you, it’s just a bummer. The player may soldier on out of defiance, or irritation, or just a basic acceptance that this is how games are supposed to be, but their experience has been diminished nonetheless. I had recognized these pitfalls when they were part of a linear storyline, but Bruce’s comment helped me see that the same principle applied to even the tiniest plot points in open-world games. All random obstacles are, on some level, crafted with an “imagine the look on their faces when” mentality, which can also be loosely translated as, “Hey! Hey! I designed this! Look at the big brain on me!” The game isn’t supposed to be about us. The player must be the star, and the designer as close to invisible as possible.

The key difference between a gameplay challenge and a betrayal, I realized, was whether the player had a fighting chance to avoid it. So rather than eliminate the flooding, I introduced different kinds of bridges.A wooden bridge was cheap, and would get the railway up and running right away. A fancy stone bridge was more expensive, and took longer to build, but would be impervious to flooding. By giving the player control over how much risk they would tolerate, the floods not only stopped feeling unfair, they became a source of genuine reward. To imagine their bridge emerging whole from the receding water line felt better than if it had never flooded at all.”

—Sid Meier, Sid Meier’s Memoir:

Paul Graham, The Power of the Marginal:

“There are real disadvantages to being an insider, and in some kinds of work they can outweigh the advantages.

Imagine, for example, what would happen if the government decided to commission someone to write an official Great American Novel. First there'd be a huge ideological squabble over who to choose. Most of the best writers would be excluded for having offended one side or the other. Of the remainder, the smart ones would refuse such a job, leaving only a few with the wrong sort of ambition. The committee would choose one at the height of his career — that is, someone whose best work was behind him — and hand over the project with copious free advice about how the book should show in positive terms the strength and diversity of the American people, etc, etc.

The unfortunate writer would then sit down to work with a huge weight of expectation on his shoulders. Not wanting to blow such a public commission, he'd play it safe. This book had better command respect, and the way to ensure that would be to make it a tragedy. Audiences have to be enticed to laugh, but if you kill people they feel obliged to take you seriously. As everyone knows, America plus tragedy equals the Civil War, so that's what it would have to be about. When finally completed twelve years later, the book would be a 900-page pastiche of existing popular novels — roughly Gone with the Wind plus Roots. But its bulk and celebrity would make it a bestseller for a few months, until blown out of the water by a talk-show host's autobiography. The book would be made into a movie and thereupon forgotten, except by the more waspish sort of reviewers, among whom it would be a byword for bogusness like Milli Vanilli or Battlefield Earth.

Maybe I got a little carried away with this example. And yet is this not at each point the way such a project would play out? The government knows better than to get into the novel business, but in other fields where they have a natural monopoly, like nuclear waste dumps, aircraft carriers, and regime change, you'd find plenty of projects isomorphic to this one — and indeed, plenty that were less successful.

This little thought experiment suggests a few of the disadvantages of insider projects: the selection of the wrong kind of people, the excessive scope, the inability to take risks, the need to seem serious, the weight of expectations, the power of vested interests, the undiscerning audience, and perhaps most dangerous, the tendency of such work to become a duty rather than a pleasure.”

—Paul Graham, The Power of the Marginal

The Power of the Marginal (paulgraham.com)

Terry Rossio, Wordplayer: "Swagger":

“I offer one of my most cherished insights. Closely-guarded until now. I actually hate to put it out into the world, but then, maybe few writers will read this. And most who do won't get it or won't agree, and I'll just keep using it myself.

…

When developing a new story, or perhaps in the context of planning a revision, one of the key questions to ask is — where's the swagger? Which character has swagger — or which character lacks it, and strives to gain it? Think of your favorite film. It's almost guaranteed it features one amazing key character that you love, and it's almost guaranteed that character arrives on screen with swagger.

James Bond has swagger. Indiana Jones has swagger. Rick Blaine has swagger, despite his pain and cynicism (perhaps because of it). Ripley has swagger. Bugs Bunny has swagger. Ferris Bueller has swagger. Dr. Frank-N-Furter has swagger. Mary Poppins has swagger. Interestingly, Clark Kent is nearly devoid of swagger, while Superman possesses unwavering swagger. Similarly, Don Diego de la Vega feigns anti-swagger, while Zorro flaunts swagger. Sherlock Holmes showcases intellectual swagger.

…

So what is swagger? We could talk about confidence, belief in oneself. Bravado. A sense of mastery over one's environment. Or possessing a brazen style — but no. It's best to not define it.

…

Actors love to play swagger. One fabulous advantage of thinking in terms of swagger comes when speaking to executives and producers. They tend to love the idea. You can see a light bulb go off. First, they find it appealing to distill the complexities of story and character design down to a basic guideline, no matter simplistic or ill-defined. At least it's a guidepost, a tool they can adopt with ease.

…

There may be a problem if none of the characters in a screenplay possess swagger, or significantly cares to seek it. Quite often, a listless project can come to life by meeting the challenge of imbuing a character with swagger. A small adjustment (addition or subtraction) in swagger often can turn a story around.”

—Terry Rossio, Wordplayer: "Swagger"

Stories are supposed to be fun.

Children play all of the time — everything they do is some kind of game. At some point, adults seem to forget this chronic playfulness; the grand sense of adventure which celebrates the small pleasures of life, an eagerness and earnestness which seeks to explore every crevice of the world, daydreaming of castles and dragons, searching for surprises and the small magical gifts that life delivers to the people who are ready to embrace new experiences.

Literature, and movies, are about escapism.

Audiences desire to escape into a better world, a brighter world, a place of hope and optimism, to experience an intensified, accelerated compression of life — touring elegant cathedrals of opulent wealth and majestic power, plundering treasure from haunted dungeons, vicariously experiencing breathtaking sex and romance and passion, suffering crippling injuries and enduring terrifying nightmares and yet somehow persisting… surviving… triumphing against impossible predicaments.

Competition and victory.

Winning at the highest level. Romantic conquests; financial conquests; institutional conquests… reframed into spiritual triumphs.

The consequences of a consequential life.

Romance, and romanticism, are a forgotten art.

Because more than anything, fictional stories give meaning and purpose and logic to a world that often seems chaotic; empty; meaningless.

Stories should be fun, they should be thrilling myths where heroes endure the best and worst aspects of life, venturing across a spectrum of extremes — and the events of a story should be thematically designed and sequenced and choreographed so that the story functions as a moral parable that implicitly communicates a powerful, spiritual lesson to the audience. The moral lesson is more effective when it remains unspoken, and the story’s events provide tacit clues to the audience.

A good story is like a jigsaw puzzle that the audience assembles in their own mind, from scattered pieces to a coherent, gorgeous mosaic. When this happens, the audience feels a sense of ownership — they feel as if they figured out the story by themselves, without help, and in their own mind, the story belongs to them personally instead of the author or director or artist who actually created it.

It’s their story, not the author’s. The narrative reflects their life, hopes, dreams, ambitions, anxieties — the character’s struggle personifies, mirrors, and echoes their own life.

This public story now belongs to them.

Artists create art for themselves, and understandably shy away from this interaction, the loss of ownership conducted by any successful exchange of ideas.

Beginner storytellers make one set of mistakes — sloppiness that comes from having no idea what they are doing, creating derivative work trapped in imitation of their favorite performers, introducing plots and characters and cliffhangers that go nowhere, designing clumsy societies and economies and characters which behave inconsistently to move the plot forward, awkward exposition which contradicts previous details. Beginners simply need to keep practicing and developing their talents — to regularly show up at the gym and get their repetitions in.

Amateur flaws are solved by practice.

Experienced storytellers make a different set of mistakes. And these mistakes are harder to correct, more difficult to evaluate, because even when people instinctually recognize that something isn’t working, casual fans are unable to cogently identify the problem’s source and articulate an actionable solution. At best, they will say something along the lines of, “I don’t get it”, or “This isn’t working for me”... a vague rejection based on emotions. The rejection is correct, but not particularly helpful.

The most common mistake I see among skillful artists is that they forget to make their work fun — they forget to incorporate a sense of wish fulfillment into the narrative.

Experienced writers have spent so many years refining their technical ability, researching the classics, dissecting theory, developing their craft in isolation and obscurity, building their tools, practicing their routine — they have completely lost touch of their inner kid. By applying discipline and professionalism and organization to their art, they have bludgeoned and obliterated the original sense of play, of innocence, of wonder and discovery, until the work has become almost a type of masochistic, scholarly punishment. Now their art tries to be “serious”, to be “important”, to be “intellectual”. All of this is good, and admirable, but melodrama and adult considerations need to be contrasted against the innocence… discovery… uncertainty… exhilaration… and carefree, reckless confidence of childhood in the full enthusiasm of ignorance and adolescent immaturity.

Professionals forget what it’s like to be an amateur: unburdened by responsibilities, untainted by the need to make money to provide for a wife and kids, undiminished by rejections and humiliations, unconcerned with respect and prestige — simply having fun. Playing around. Exploring. Relaxing. Learning. Wasting time. Indulging in trivial distractions. Experimenting… and swiftly, effortlessly discarding anything that doesn’t work.

Veteran writers spend so much time developing their tools, and techniques, they lose sight of the questions to ask, which goals to aim at, the purpose of art, and what the audience is looking for.

Audiences want to have fun.

Authors create art in a completely different way than audiences consume, and enjoy it.

The emotional interaction between the audience and media entertainment occurs in three stages — before, during, and after the performance. There is expectation before a movie, immersion during a movie, and contemplation and recontextualization after watching the film. Each of these emotional processes can be dissected and mastered, and they serve a different purpose.

A movie trailer serves to excite the audience, to tease and stimulate potential customers, to tempt and seduce fans to make an active choice to attend a nearby theater and then buy a ticket. The movie trailer, or the book jacket, or the comic book cover, or the pilot episode of a television show serves to stimulate the audience’s imagination — hinting at bigger questions. Foreshadowing the development, elaboration, and recapitulation of the initial concept. Delivering a cheap sample to upsell the larger course.

During art, audiences want to lose themselves completely in the experience, to forget the anxieties and insecurities and stress of their real-world lives. From scene to scene, suspense drives the narrative forward. What will happen next?

Afterwards, the audience rethinks the experience — it’s at this point they demand meaning, some kind of moral lesson, transformative character arc, or coherent narrative structure which provides a clear trajectory. Then the intellectual payload is digested, internalized, and sporadically applied to their own lives. The best art functions on multiple layers, and rewards repeated sessions, provides more and more insights with prolonged contemplation and intellectual excavation of the material.

Talented, experienced artists focus so much on being serious and bleak and stylish — they emulate True Detective, or Breaking Bad, or Blood Meridian, or Fyodor Dostoevky — they chase the wrong goals because everyone agrees that the prestige of a magnum opus deserves admiration.

Technical mastery of a nonlinear narrative structure, or the interludes of an epistolary novel, or the intercutting layers of a nested frame story are all very cool when they’re performed correctly. But what makes a story work is the engine of relatable, vulnerable characters dramatically chasing frustrated desires… basic, primitive emotional substance — the universal psychology and competitive instincts which drive every human being.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

True Detective is about family, brotherhood, justice, the rivalry and friendship of two dangerous men, the slow erosion of time, the incremental decay of a family and career and community.

Breaking Bad is about money, class, obligations, ambitions, status anxiety, a father and husband’s responsibility to provide for his family, the realization of death and the confrontation of mortality, the jealousy of a frustrated genius watching as his peers outcompete him.

Deep, universal emotions.

A focus on technique often distracts from what makes the story succeed, or fail — struggling characters who provide fiction’s dramatic engine.

Let’s apply this abstract theory to some concrete examples, and compare how different movies explore the same theme by delivering, or neglecting wish fulfillment.

There are two movies which explore the 2008 American subprime housing crisis: Margin Call, and The Big Short.

Margin Call is a low-budget film which earned $20 million at the box office; The Big Short earned $133 million. The films are quite different, but cover the same event.

The main difference is character viewpoint.

Margin Call is a depressing film — a hedge fund of investment bankers realize the market is on the precipice of collapse, and after much agonizing and deliberation, they dump their fraudulent portfolio onto an unsuspecting economy, which wrecks tens of millions of lives. Everyone in this film is some flavor of scumbag, or a bystander complicit in the institutional corruption of the financialized economy. The movie is very educational, it does a great job of explaining how Wall Street derivatives work and applying this abstract, opaque mathematical valuation to the personal emotional struggles of an ensemble cast, and the plot is structured as a suspense-driven thriller. Margin Call features beautiful camerawork, marvelous dialogue, elegant sets, sophisticated acting, and literary symbolism; metaphors; allegories which deepen the film’s brilliance. It’s a well-crafted masterpiece.

But Margin Call is not a “fun” movie, and as much as I enjoy studying and analyzing the craftsmanship exhibited by the movie, I would not want to watch it to relax. It’s extremely depressing. There are no heroes.

The Big Short is brilliant because it makes a counterintuitive decision to change character viewpoints. Instead of telling the story of Wall Street’s criminals, or its ordinary victims, The Big Short tells the story of the 2008 financial crisis from the perspective of three financial underdogs who got rich by betting AGAINST the market, betting against the big banks. It’s a sort of ensemble mystery story which cuts between the socially awkward maverick of Scion Capital, the greedy young investors of Brownfield Fund, and the cynical, jaded insiders of FrontPoint Partners.

The Big Short tells a complex, historically accurate narrative of financial fraud in which almost everyone is corrupt, parasitic, incompetent, or oblivious — but gives the audience three sets of brave, resourceful, diligent underdog heroes to root for. This movie finds a note of redemption amid a bleak, depressing tragedy of global deceit, theft, bankruptcy, and the subsequent economic fallout.

One of the most important decisions a storyteller can make is to choose the right character viewpoint to tell a story. This completely changes the story’s meaning. All the events can even remain the same. But how the audience feels is completely different, because fans experience the same highs and lows as the main character, and their interpretation is shaped by the character’s perspective.

Choose someone heroic.

Another example, sleazier and more sordid than financial fraud: pornography and sex trafficking.

Two movies tell the story of a father’s attempt to rescue his daughter from a dehumanizing life as a prostitute: Paul Schrader's Hardcore (1979), and Taken (2009).

Probably you have never heard of Paul Schrader's Hardcore (1979), and that’s because it’s a completely depressing movie. There’s no wish fulfillment. In contrast, Taken (2009) is a famous action franchise which grossed more than $900 million over a six-year period with a film trilogy starring Liam Neeson, had a brief spinoff television show, and spawned countless memes and Internet jokes about “I don’t know who you are. I don’t know what you want. If you are looking for ransom, I can tell you I don’t have money. But what I do have are a very particular set of skills… Skills that make me a nightmare for people like you.”

In technical and literary terms, Paul Schrader's Hardcore (1979) might be considered a masterpiece, and Roger Ebert gave the film a 4-star review, the highest possible score. But the movie was forgotten almost as soon as it was released because it’s a relentlessly downbeat, grim, pessimistic narrative.

Roger Ebert, Hardcore (Movie Review):

“They have moments in the movie when they talk, really talk, about what's important to them and we're reminded of how much movie dialogue just repeats itself, movie after movie, year after year… the father and prostitute talk about sex, religion, and morality, and we're almost startled by the belief and simple poetry in their words. This relationship, between two people with nothing in common, who meet at an intersection in a society where many have nothing in common, is at the heart of the movie, and makes it important.

…

Scott vows to follow his daughter into the sexual underworld and bring her back. His efforts to trace her, through San Francisco and Los Angeles and San Diego, make Hardcore into a sneakily fascinating guided tour through massage parlors, whorehouses, and the world of porno movies… all the other lost young girls who drift to California and disappear.

…

She has a deep psychological need for a father figure, a need she thinks Scott can meet. She also has insights into Scott's own character, insights his life hasn't previously made clear to him. There's a scene near the waterfront in San Diego that perfectly illuminates both of their personalities, and we realize how rare it is for the movies to show us people who are speaking in real words about real things. The movie's ending is a mess, a combination of cheap thrills, a chase, and a shoot-out, as if Schrader wasn't quite sure how to escape from the depths he found.

The film's last ten minutes, in fact, are mostly action, the automatic resolution of the plot; the relationship between Scott and Hubley ends without being resolved, and in bringing this story to a "satisfactory" conclusion, Schrader doesn't speak to the deeper and more human themes he's introduced. Too bad. But Hardcore, flawed and uneven, contains moments of pure revelation.”

—Roger Ebert, Hardcore (Movie Review)

Prescott Gilbert, American Hardcore:

“Upon release the film was met with largely negative reviews. It’s been somewhat reappraised in recent years. Schrader himself is highly critical of the final product, specifically with the compromised “happy” ending, which we’ll get on to. But this film is more prescient of modern America than many would realize. What, on the surface, may seem like a snapshot of a specific time and place is oddly prophetic about where the country as a whole was headed.

The film begins with a look at the life lived by the Calvinist community of Grand Rapids, Michigan. Their home is peaceful and isolated. Unconcerned with the morals and attitudes of metropolitan areas such as New York or L.A., they live their lives conservatively and ignore the changing social attitudes of the country around them. They believe the outside world can change but their community will not. They will live their life their way regardless of the world around them. This community is basically a stand-in for any conservative white middle-class community in America.

Van Dorn is the portrait of white middle class masculinity: tough, reserved—and out of shape… The film is something of a loose retelling of John Ford’s The Searchers starring Wayne, in which a man attempts to locate his niece, who has been kidnapped by the Comanche, only to find that she has become accustomed to the Comanche’s way of life. Swap out the old west for 1979 and the Comanche for the seedy porn inhabitants and it’s essentially the same story. Many inhabitants of today’s shrinking white middle class still cling to this kind of old-school conservatism, harkening back to the era of Wayne, and believe that one day the country will return to this brand of thinking. They refuse to acknowledge that it’s actually part of the problem.

Van Dorn and his community do not approve of the morals of the outside world but do nothing to prevent it. They choose to isolate themselves from the outside world. They believe this is enough to keep them safe. They believe the world outside their home will remain outside and that they will remain untouched by it. But this, of course, is a delusion: the outside always gets in. It’s just a matter of time.

…

In attempting to locate his daughter Van Dorn like any conservative man first attempts to use the police, the system, with all their official rules and red tape. It isn’t until the system has proven it is incapable of helping that he takes matters into his own hands… He aimlessly enters porno-book stores, massage parlors, sex shops, and porno theaters asking questions that get him nowhere and ultimately only lead to him getting beat up and thrown out of one establishment. He attempts to be reasonable and forward in an unreasonable and backwards environment. When this approach fails to get him any closer to his daughter he realizes he must change his tactics…

Violence allows him to enter this new world completely. Van Dorn first becomes acquainted with the use of violence when he beats information out of one of the men who appear in the porn film with his daughter…

…

Van Dorn now utilizes violence with ease as it is the method he knows is his only hope for finding his daughter.

…

In the film Van Dorn remarks on how every aspect of American society is based around sex. Music, TV, fashion, advertising—everything. It was true in 1979. It’s even more true today. The main difference is that it used to be more subtle, more subliminal. It was still at a remove from daily life. Beyond the suggestion, you had to seek it out to get your hands on it. Today it’s right there, on the surface, everywhere you look. Much of what is shown in the film, however shocking it was in 1979, would seem tame compared to what you’d find online today. Today the threat is inside every home with an internet connection. That is the America we now live in, the America Hardcore tried to warn us about, even if it could never have predicted the rise of the internet or Pornhub and OnlyFans.”

—Prescott Gilbert, American Hardcore

American Hardcore - Film Review by Prescott Gilbert (mansworldmag.online)

Between two films which cover the same theme, same plot structure of a father rescuing his daughter from being sex trafficked by pimps, and more or less the same content, Paul Schrader's Hardcore (1979) is the more realistic film. It may even be more intelligent. But Taken (2009) is a popular, beloved global franchise because it’s fun — it finds an uplifting way to explore the sordid underbelly of civilization.

The Taken franchise is downright goofy.

Fans ridicule the action choreography and film editing of the sequels; in one famous scene, twelve camera cuts are utilized in order for the aging Liam Neeson to pretend he jumped over a fence. Stuntmen laugh about the sloppy, obvious artifice. But this mockery comes from a place of genuine affection, a guilty pleasure. We all enjoy watching sex traffickers getting brutalized by the righteous fury of a father protecting his kidnapped daughter.

Every day in America, some horrified father learns that his beloved daughter has become a prostitute, or is doing porn. It happens all the time to ordinary, unremarkable men.

The idea that a retired CIA operative would discover his daughter has been kidnapped, is about to be sex trafficked, and immediately he borrows a private jet from his ex-wife’s billionaire new husband in order to fly to Europe and go on a killing spree by himself across the Albanian criminal underworld — this is inherently a goofy, surreal, and ridiculous premise. But we love it. And it manages to take a real problem, with the most loathsome and nauseating content, and turn this repulsive conflict into a wholesome, family-friendly global franchise with a satisfying happy ending through the application of a wish-fulfillment power fantasy.

Taken is a clean movie, which prevents innocence from being contaminated. The film teases, foreshadows, and flirts with tragedy — but never wallows in it, and never allows anything bad to happen to the main characters. Only the secondary, supporting characters are destroyed.

In the movie Taken, Liam Neeson’s daughter never loses her virginity — she is auctioned off to an obese Saudi billionaire, which sets up a climactic final battle on the sheikh's private yacht.

The daughter’s best friend is beaten, drugged, abused, and found dead after a drug overdose — this serves to heighten suspense, and provides a clue to solve the film’s overall mystery plotline. But the tragic annihilation of a cameo supporting character doesn’t tarnish the film’s eventual happy ending.

It’s not a realistic outcome, but that’s the point.

If I wanted something realistic, I would watch a documentary, or read a biography.

Realism lubricates the fantasy by easing the burden of suspension of disbelief — realism is not the primary goal of art. It’s a situational technique, a tool which is perfectly appropriate for some storylines, and quite wrong for others.

Robert Louis Stevenson, Familiar Studies of Men and Books: “Chapter One: Victor Hugo’s Romances”:

“Lastly, I suppose one must say a word or two about the weak points of this not immaculate novel; and if so, it will be best to distinguish at once. The large family of English blunders, to which we have alluded already in speaking of LES TRAVAILLEURS, are of a sort that is really indifferent in art.

If Shakespeare makes his ships cast anchor by some seaport of Bohemia, if Hugo imagines Tom-Tim-Jack to be a likely nickname for an English sailor, or if either Shakespeare, or Hugo, or Scott, for that matter, be guilty of "figments enough to confuse the march of a whole history — anachronisms enough to overset all, chronology," the life of their creations, the artistic truth and accuracy of their work, is not so much as compromised.

But when we come upon a passage like the sinking of the "Ourque" in this romance, we can do nothing but cover our face with our hands: the conscientious reader feels a sort of disgrace in the very reading.

For such artistic falsehoods, springing from what I have called already an unprincipled avidity after effect, no amount of blame can be exaggerated; and above all, when the criminal is such a man as Victor Hugo.

We cannot forgive in him what we might have passed over in a third-rate sensation novelist. Little as he seems to know of the sea and nautical affairs, he must have known very well that vessels do not go down as he makes the "Ourque" go down; he must have known that such a liberty with fact was against the laws of the game, and incompatible with all appearance of sincerity in conception or workmanship.”

—Robert Louis Stevenson, Familiar Studies of Men and Books: “Chapter One: Victor Hugo’s Romances”

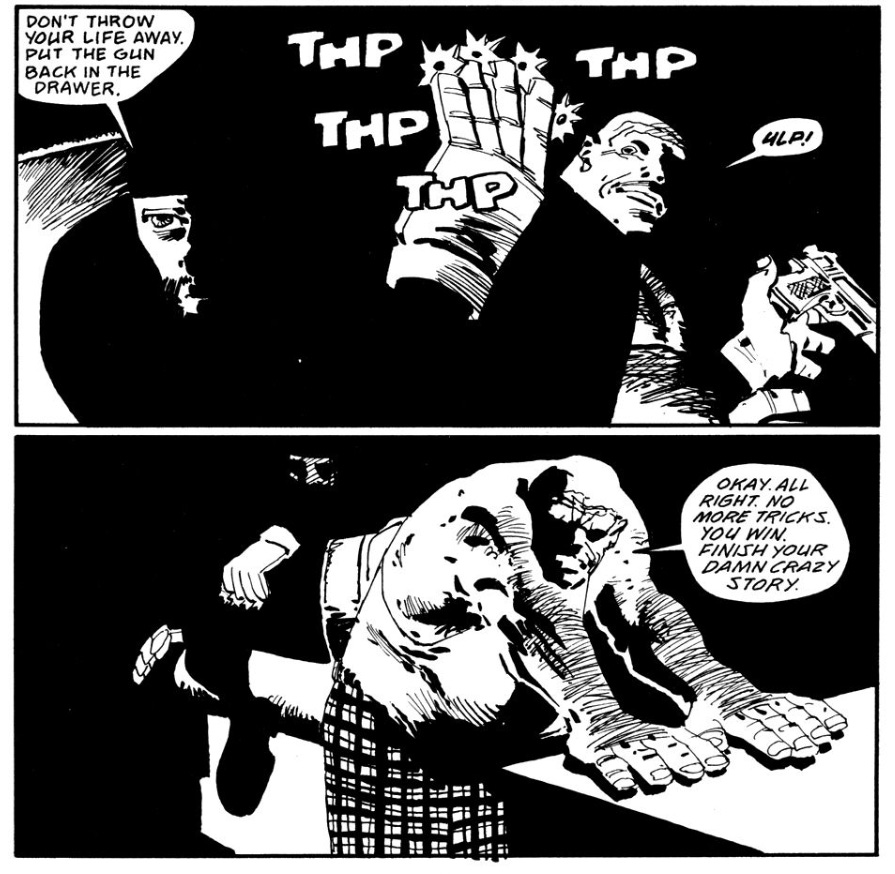

Taken (2009) is more or less a retelling of Frank Miller’s Sin City: “Hell and Back” comic book miniseries (1999-2000). Some of the scenes are more or less identical — there is a scene in Taken where Liam Neeson confronts an old friend, a dirty police chief, at the man’s house and baits him by emptying the bullets from his pistol. That scene occurs in more or less the same fashion in the “Hell and Back” comic miniseries. Frank Miller’s hero is a retired, highly decorated veteran who is virtually unstoppable — inspired by the Rambo franchise.

Stories build on stories.

Wish fulfillment is a crucial aspect of any popular franchise, and the missing ingredient to many failed novels and underappreciated films which are smart, bold, beautiful failures.

James Cameron’s Avatar is an archetypal example of how to incorporate wish fulfillment into a narrative.

In Avatar, a handicapped war hero… a sympathetic, aspirational underdog… travels to a distant planet where he pilots a clone body in a bioluminescent forest. His braided hair functions like a USB port/cable, and he’s able to plug into local animals like a video game, and then ride galloping, crawling, swimming, flying beasts like vehicle upgrades.

It’s theoretically possible — but statistically improbable — that life on an alien planet would somehow evolve into this kind of symbiotic video game ecosystem, plugging into wild animals and piloting them for precarious adventures.

The science is ridiculous, but it doesn’t matter.

It’s fun.

And that’s what all stories should be. Not completely unrealistic, not desperately watered down. But there should always be someone for the audience to root for. And even if the tragic hero ends up ruined and humiliated, there should be exciting, intoxicating memories along the road to decimation.

The side-by-side comparisons of the same movie/story (both competently produced) through the WISH-FULFILLMENT/SWAGGER style and the GRIM/DOCUMENTARY style was fantastic - having seen many of the films you mentioned, the contrast is something many moviegoers may notice at the subconscious level, but have a hard time articulating; you laid it out in a succinct and powerful fashion.

This is great. I have been unconsciously doing this for my works, trying to make sure that the story is fun. My problem was the opposite, trying to maintain the story structure and not make it fun for funs sake and forgo everything else I am supposed to do. My last major problem was having was the moral theme incorporated into the story like you mentioned, but the book 'The Anatomy of Story' helped with that. Fantastic article!