Spoilers below.

M. Night Shyamalan has enjoyed a very weird Hollywood career. He directed two forgettable, unremarkable films before his third movie, “The Sixth Sense” launched him into the cinematic stratosphere of wealth, power, and celebrity. For a while, Hollywood studios hoped that M. Night Shyamalan would be the blockbuster equivalent of Stephen King, someone who could establish a profitable artistic brand as a widely-beloved auteur capable of releasing tentpole franchises on a regular schedule; someone who could tap into the horror genre and a variety of intriguing plot twists to package mainstream films into a sanitized, easily-digestible format which would appeal to audiences of all ages, all around the world.

In other words, he was wrongly assumed to be an A-list film director who could direct anything he wanted, and draw a massive crowd.

At first, M. Night Shyamalan lived up to the hype. He had an amazingly profitable, and decently entertaining run of three consecutive lowbrow films which satisfied audiences: The Sixth Sense (1999), Unbreakable (2000), and Signs (2002), which collectively grossed a little more than $1.3 billion.

His career tanked with the profitable but intensely-despised movie The Village (2004), followed by a series of artistically hollow films which managed to eke out acceptable profits: Lady in the Water (2006), The Happening (2008), The Last Airbender (2010), and After Earth (2013).

There was a mismatch between the universally-popular, critically-acclaimed director that studios craved, versus his reality as a niche creative storyteller with a clear sense of his own identity.

The studios wanted M. Night Shyamalan to direct expensive movies with hundred-million-dollar budgets, and for these movies to bring in a baseline of half a billion dollars, up to a billion dollars. Sometimes he came close to this dream. Other times he suffered embarrassing failures.

Over the years, M. Night Shyamalan drifted into his comfort zone — he is a talented horror director who produces fun, brainless popcorn flicks which are filmed on a cheap budget… and end up grossing three to five times their production and marketing costs. His camerawork is solid but mechanical. His movies are sensational but dumb. The more you think about a M. Night Shyamalan film, the more the plot’s logic begins to fall apart, because the behavior of his characters is inconsistent, their emotional motivations are weak or nonexistent, and the plot holes are wide abyssal gulfs large enough for a titanic, slime-encrusted Cthulhu to slither through.

“Trap” (2024) is going to be quite profitable, but it’s a very stupid movie, punctured by a long list of errors and contradictions and nonsensical creative decisions.

For this reason, “Trap” (2024) is an excellent example for creative storytellers to dissect, study, and learn from.

Every story is designed around the phrase “A hero wants something, but _____”.

Aaron Sorkin formulates this dramatic logic in the terms, “Intention” and “Obstacle”.

Aaron Sorkin explains:

“What I need before I can do anything is an intention and obstacle. Okay? Somebody wants something. Something's standing in their way of getting it. They want the money. They want the girl. They want to get to Philadelphia. It doesn't matter. But they've got to really want it bad, and whatever is standing in their way has got to be formidable. I need those things, and I need them to be really solid, or else I will slip into my old habit, back when I was 21 with the electric typewriter, of just writing snappy dialogue that doesn't add up to anything.

…

Once you have that intention and obstacle, now, like a clothesline, you can start hanging those cool stories from the real trip across the country that was the reason you wanted to do this whole thing in the first place. You have to build the drive shaft first. And that drive shaft can only be intention and obstacle. That's what creates friction and tension, and that's what drama is. If you don't have that, then it's journalism.”

—Aaron Sorkin

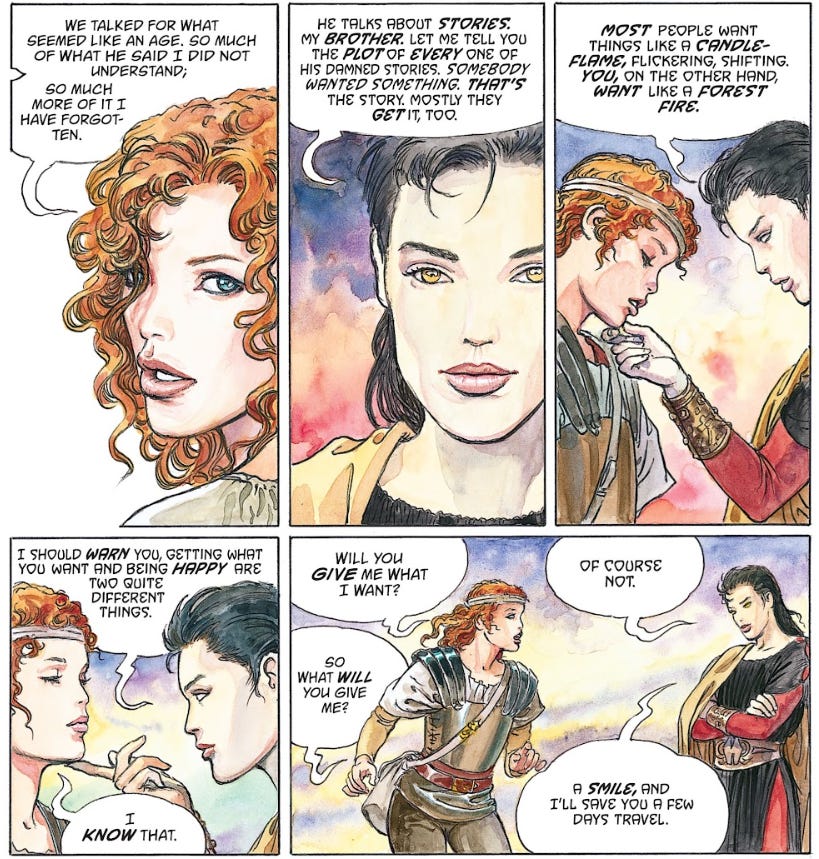

Or, as Neil Gaiman writes:

“He talks about stories, my brother. Let me tell you the plot of every one of his damned stories: Somebody wanted something. That’s the story. Mostly they get it, too.”

—Neil Gaiman, The Sandman: Endless Nights: “What I’ve Tasted of Desire”

Fundamentally, every plot can be reduced to four elemental components: Character, Goal, Obstacle, Stakes. This is one of the most rudimentary lessons of narrative design, which every screenwriter or novelist encounters, absorbs, and internalizes at the beginning of their career.

Every plot can be framed as: A character has a goal, but they are prevented from achieving this goal due to a seemingly insurmountable series of obstacles. Despite a constant escalation in danger and intensity, the hero cares enough to keep struggling and chasing this goal because of heartfelt emotional stakes. Eventually the accumulated struggles and sacrifices involved with this quest results in a climactic moment of truth, which resolves (or fails to resolve) the original problem and related dramatic question.

Very basic stuff.

Dan Brown, the author of The Da Vinci Code, identifies that every plot needs dramatic momentum based on three components which he refers to as the 3 C’s: Contract, Crucible, and Clock.

Dan Brown declares:

“I was excited to learn as a young writer, as I started to put this together, talking to other writers, talking to great writing teachers, that there are elements that must be in a good story. Not just thrillers, all stories. We're gonna talk about thrillers here primarily, but all of this is relevant to a storyteller. Whether you're writing a memoir or a screenplay, this is about storytelling. And there are elements that all good stories have.

…

Now they may be crafted a little bit differently, put together differently, but they're all there. The same thing with stories that work. They all have the same elements. We're gonna talk a lot about what those elements are in this class. In broad strokes, you might have a world. You might have the sole dramatic question.

You've got to have a hero. You've got to have a goal. Your hero has to have something he or she wants to accomplish. You have to have obstacles that make it impossible. You have to have a moment when the hero conquers the villain, when good conquers evil. These are all elements that you're going to find in stories that work. And we're gonna talk about them more in-depth in a little while.

When I sit down to write a book, I think in terms of what I call the three C’s that I think could be very, very helpful to anyone who's sitting down and trying to outline and write a thriller. I call them the contract, the clock, and the crucible.”

—Dan Brown

So, what are the 3 C’s?

In popular fiction, what is a Contract, a Clock, and a Crucible?

Contract — the unspoken, implicit relationship between the author and the audience. Every audience has inchoate, unconscious expectations which they expect the author to surprise, subvert, or satisfy. These intangible psychological promises are communicated by the author to the audience, and a fun, intelligent story should reliably deliver on these promises.

Clock — drama is heightened by the urgency of a time limit. Countdowns intensify danger. This clock might be represented by a ticking bomb, a sinking ship, a leaking submarine, a punctured zeppelin hissing as gas escapes from the blimp, or a multinational corporation which is losing billions of dollars per minute. Urgency panics characters, and unsettles the audience. The crisis must be solved immediately, or some kind of severe catastrophe will occur.

Crucible — The hero is trapped with a problem. Sometimes this scenario is achieved by physically stranding the hero on an island, or shackling a kidnapped character to the floor of a serial killer’s basement. Sometimes this is achieved financially, by requiring an impoverished hero to compete in pursuit of money. Sometimes this is achieved emotionally and psychologically, by creating a problem which the hero’s identity feels compelled to solve… for example, when an amnesiac hitman struggles to remember his previous identity… or when a jealous wife discovers her longtime husband is having an affair, so she attempts to pressure the husband to dump his mistress and reconcile their marriage. Technically, a man with amnesia is not going to die if his memories remain permanently repressed. Technically, a jilted wife can survive her husband’s betrayal, and a subsequent divorce. These are not life-and-death problems… but they are universal, sympathetic, and powerfully resonant struggles which make logical, dramatic sense for characters to ferociously pursue.

TLDR: Every plot features a character who wants something, who is then frustrated by problems, who then persists because of a passionate psychological motive. Drama promises spiritual meaning to an audience, which is delivered on a compressed timetable, based on problems that are imminent, which the characters cannot figure out how to avoid.

To continue with this foundational review of essential dramatic structure, there are four elemental components to any dramatic interaction… One: Introduction of a question, problem, or character. Two: Escalation or intensification of the problem. Three: A complication or plot twist which redirects the situation in an unexpected direction. Four: Resolution of the problem, which provides emotional, intellectual, philosophical significance to the hero’s struggle.

The author of JoJo's Bizarre Adventure clarifies that these four stages of a scene are the essential building blocks of any plot:

Araki Hirohiko, Manga in Theory and Practice:

“1.) Introduction: Introduce the protagonist to the reader. The important part here is to have the protagonist appear as quickly as possible. The reader mustn’t think, When the hell is the main character going to show up?

2.) Development: The protagonist encounters the antagonist or some hardship, etc.

3.) Twist: The protagonist rises to face the challenge, but an additional problem creates a dilemma. In this part of the story, the protagonist attempts to strike back at antagonist/hardship but the difficulties keep building, and the readers keep turning pages to find out what will become of the protagonist.

4.) Resolution: A victory or other happy end.”

—Araki Hirohiko, Manga in Theory and Practice

So, having reviewed these introductory steps of how to design compelling fiction which captures, retains, sustains, and finally rewards the focus of an attentive audience, let’s return to M. Night Shyamalan’s Movie “Trap” (2004).

In the horror-oriented, psychological thriller “Trap” (2024), a serial killer named Cooper Adams attends a music concert with his teenage daughter. He is trapped in an elaborate police ambush. An army of armored SWAT police block the concert’s exits, while uniformed policemen march through the crowd and search for the elusive serial killer. A cat-and-mouse game begins. During the coordinated government manhunt, Cooper Adams sneaks around the crowded stadium and randomly kills innocent civilians, in order to distract the police and taunt his pursuers by demonstrating their inability to stop his murders.

In theory, this is a cool and dramatic plot scenario. It’s an asymmetric competition. A serial killer is committing random crimes in a crowded public venue. A vast army of law enforcement agents are trying to identify, and arrest the unknown serial killer. There’s a Clock, in the sense of an ongoing manhunt. The music concert, blockaded by police, functions as an enclosed Crucible. The story is a fast-paced, suspenseful battle of wits between a sadistic renegade genius and a conformist, law-abiding society in the tradition of adventures like the anime Death Note, where Light Yagami uses supernatural methods to execute antisocial criminals, besieged by an elite police unit which attempts to trick him into revealing his true identity. The serial killer’s “win condition” is to outsmart the police. The police department’s “win condition” is to exploit the serial killer’s ego… provoking his vanity to conduct signature murders which will accidentally unmask specific details that can be traced back to him.

In theory, “Trap” (2024) is a brilliant psychological thriller which adheres to a classical, proven formula that has been refined and perfected by decades of suspense fiction.

But if you think about this plot for more than a couple minutes, the whole scenario is really fucking stupid.

The police don’t know what Cooper Adams looks like. The police are not able to detain an entire stadium of 30,000 civilians for more than 24 hours to catch a single murderer. Only one piece of evidence exists which can destroy Cooper’s life — his phone is livestreaming footage of a kidnapped victim who Cooper Adams plans to execute. The scene on his phone resembles one of the torture chambers from the Saw franchise.

If the police find Cooper’s phone at the start of the movie, his ordinary life is over, and his family will be destroyed. The smart move would be to walk into the bathroom, break his phone, flush the pieces down a toilet, return to the concert, and enjoy the rest of the day listening to bland pop music beside his teenage daughter. If he destroyed his phone, and pretended to be normal, there would be no way for the police to capture him.

The End.

We don’t have a story.

In this movie, like most M. Night Shyamalan films, the characters are written to behave in fake, implausible, and inconsistent patterns to artificially manufacture dramatic tension.

Supposedly the serial killer being hunted by the police is brilliant and elusive, which is why a huge army of police have been assembled to find him. But if we take a step back and analyze Cooper Adams, everything he does in the movie is designed to incriminate himself. It’s dumb to go on a berserk killing spree after discovering himself in an ambush. It’s dumb to kill random bystanders at a concert, because there are thousands of cameras, and even if he is able to slip unnoticed through the chaos of a crowd, local camera footage can be replayed by the police. It’s dumb to keep checking his phone’s livestream of a kidnapped victim, rather than promptly discarding the evidence.

Everything he does in this movie is stupid because it calls unnecessary attention to himself.

From a storytelling perspective, the desired outcome is brilliant, and it’s awesome to create a suspenseful cat-and-mouse game played between an elusive fugitive and the limitless resources of a surveillance state. The problem is the initial setup, which suffers fatal design flaws, and cripples the subsequent plot events with glaring logical contradictions.

It’s actually a very easy fix.

The police need to be given better clues, in order to justify the investigation. By strengthening the police, and clarifying their reconnaissance with more accurate, actionable data, most of the plot would be coherent and dramatically satisfying.

(Spoilers Below)

Near the end of the movie, Cooper Adams discovers that the police found a partially-torn concert receipt in a vacant house he owned… and that the concert ticket was planted there by Cooper’s wife. She had long suspected that he was a serial killer, and conspired to entrap him in an ambush, so she could be free from a terrified, horrified marriage with a monster.

On one level, this is great writing — there’s an incredible emotional payoff delivered by the serial killer discovering his wife suspected, investigated, betrayed, and incriminated him. The plot twist offers a profound thematic resonance, by centering the narrative’s focus on a question of what loyalty means inside marriage, and whether the wife is justified in her decision.

But again, the plot details are clumsily designed.

A partially-ripped concert ticket gives the police a location, date, and time… but not enough to identify and capture their target. At most, the police can stand around uselessly and wait for something to happen, then leave the event empty-handed and disappointed.

Many possible solutions exist to this kind of plot dilemma. The basic answer is to provide the surrounding police blockade with better clues to the killer’s identity, in order to strengthen the efficiency and plausibility of the active manhunt.

Numerous options present themselves, in order to make this conflict work according to plausible, dramatic, efficient story logic.

One cool solution, which I find especially tantalizing to apply towards this scenario, is to provide the police with a special witness who has seen Cooper Adams during his crimes — someone who can recognize his crimes, but doesn’t know his real name… they met him when he was using a favorite alias. The most obvious version of this plot device would be that somehow one of his victims survived being kidnapped and tortured, they have been crippled and brutally disfigured, and now they are collaborating with the police. Under this scenario, the serial killer is unsure how his victim managed to escape from a sealed dungeon. At the end of the movie, it would be particularly satisfying for the serial killer Cooper Adams to discover that his wife stumbled across his hideout when this victim was being tortured, she hid inside the dungeon while the torture continued, and at some point when the serial killer stepped out to take a break from his private little playground, his wife helped the kidnapped victim escape.

Using a scarred, traumatized survivor as our manhunt’s key witness would be a conventional solution.

A more exotic, counterintuitive variant of this same method would be to introduce a second serial killer — this is the approach I would favor.

By adding a human witness (who has actionable, but limited knowledge of the serial killer’s true identity) to the manhunt, we transform the plot’s dramatic stakes. New win conditions are assigned to both the serial killer, and to the surrounding police blockade, which strengthens the ticking clock and intensifies the overall conflict.

In our new scenario, uniformed police go aisle by aisle of the concert, dragging out isolated men to be examined by the key witness. For the police, their “win condition” is to find Cooper Adams and authenticate the serial killer’s identity by using a verified human source. The serial killer’s “win condition” is to prevent this outcome by causing random mayhem to distract the police, reduce the number of bodyguards protecting the key witness, and then for Cooper Adams to penetrate local security so he can assassinate the only man who can identify him — and to achieve all this without being caught.

For many reasons, I think a second serial killer is more satisfying as a witness (and potential target) than an innocent survivor who narrowly-escaped a past torture chamber.

In cinematic, visual, and dramatic terms, we can incorporate a cool fight scene near the end of the movie, between two experienced murderers. This kind of brutal hand-to-hand combat would be compelling. The combat would seem authentically dangerous, rather than a one-sided beatdown aimed at a crippled innocent survivor. And there would be an undercurrent of betrayal to the interaction… two old friends dueling, lunging, stabbing in a dark, confined space.

Also, it’s easy for audiences to enthusiastically root for a serial killer who is killing a comparably worse monster. Audiences would be at best ambivalent, and at worst repulsed, by watching the plot-driven murder of an innocent witness.

Furthermore, it would be deeply satisfying for Cooper Adams to kill his old partner, and to believe that he’s completely escaped from the police… only to arrive home at the end of the movie, and to discover that his wife originally betrayed him. This sort of plot design is consistently surprising to audiences: to structure a second plot twist to hit immediately after one previous plot twist which the hero narrowly survives. The first surprise registers as a near-miss, a close-call… and the second twist lands with a sickening crunch.

You get the idea.

The above passages were written in order to demonstrate the mindset which is artistically productive when designing a plot. You want to aim at meticulous, logical dissection of every minor logistical detail. Every aspect of the plot needs to hold up, and then they all need to work together in concert, to form the elegant architecture of a load-bearing structure which is capable of sustained dramatic exploration of an immersive fictional world, the tortured psyche of a vast ensemble of complex characters, and a fast-paced, suspenseful conflict.

M. Night Shyamalan’s films fail this test.

He does a lot of things correctly. He invents cool scenarios. He places interesting, sympathetic characters in believable danger. But he forces the plot to go in superficially cool directions, rather than building interesting characters and allowing events to organically emerge from ambitious pursuit of their internal dramatic tension — or to take a cinematic series of events and reverse-engineer a subtle lattice of plausible, logical, psychologically complex, thematically compelling justifications which reinforce and amplify and symbolically accentuate his desired narrative outcomes.

Hopefully this analysis has been useful, rather than pedantic.

The point here is not to beat down on M. Night Shyamalan — other critics have done that already, for the past two decades. The point is to learn from a flawed genius, a goofy cinematic savant who has directed a dozen films, and grossed three billion dollars… but commits some incredible, amateurish errors.

Everything he does is almost brilliant.

His camerawork, his plots, his characters, his themes… in each case, there’s a smart idea underlying his aesthetic choices. But his actual execution ranges somewhere between very solid, to very sloppy.

The final result lacks polish.

M. Night Shyamalan’s best work, and his most impressive accomplishments, are the negotiation that he does behind the scenes in Hollywood, and his ability to market and promote his films. His movie posters are pristine, and executed with an immaculate technical fidelity that is absent from his screenplays or cinematography. And his stories reflect a provocative originality, defined by a bold willingness to take creative risks. It’s a brave and potentially shrewd choice to make a serial killer the main hero of a horror film. But again, the story was not developed correctly, and core design problems result in a technically stunted, emotionally sterile final product which falls short of logical plausibility, and fails to elicit audience sympathy.

We’ve carved into his movie’s flawed plot structure, and vivisected the corpse.

Let’s turn to an examination of character, and theme.

Again, we return to a review of rudimentary, introductory lessons into the mechanics of effective storytelling.

Heroes chase goals, these goals are dramatic, and heroic quests can adopt a wide range of motives: romance… revenge… profit… ambition… jealousy… vanity… self-discovery… loyalty… friendship… religion… patriotism… survival… the list goes on.

But more fundamentally, there are only three basic forces to propel a plot. It’s optimal to use all three of these Story Engines, because their intensity will ebb and flow, recede and swell with tidal rhythms, and when one Story Engine diminishes in strength, the other two should step up to carry the load of entertaining a mass audience.

Fear.

Desire.

Curiosity.

“Carrot and stick — have protagonists pursued (by an obsession or a villain) and pursuing (idea, object, person, mystery).”

—Michael Moorcock

https://billionairepsycho.substack.com/p/billionaire-psychos-rules-for-writing

Again, these three forces drive a story. Any story.

Fear. Desire. Curiosity.

Heroes run away from their fears, from monsters that hunt them.

Heroes chase after their desires and ambitions, towards anything beautiful and lovely and aspirational.

Heroes investigate and explore mysteries, searching for clues, seeking to understand the world… learning and growing as a result of their adventures.

Ideally, all three of these motivations should happen in a movie, comic, novel, television show, or video game.

Halo: Combat Evolved is a good example of storytelling with emotionally solid fundamentals. Master Chief displays all three of these basic impulses as he fights a relentless path of mayhem and destruction across the artificial, alien ringworld. At first, fear is an overwhelming motive. The game begins with Master Chief waking up in a lost battle, while hordes of Covenant infantry board the damaged Pillar of Autumn starship, human soldiers are slaughtered all around him, and technologically superior Covenant starships swarm the doomed spacecraft.

Fear presses hard.

But as time goes on, the Master Chief survives one impossible mission after another, and the real-world players gradually begin to feel a sense of invincibility and well-justified arrogance. Fear diminishes. Survival grows boring. In response to a long, constant chain of unbroken victories, Master Chief is fueled by increasingly proactive desires — as he fights the Covenant hordes, he seeks to organize the scattered fragments of human survivors into a disciplined army, and he plunges deep into enemy territory, doing his best to rescue the heroic Captain Jacob Keyes from being captured and stranded deep behind enemy lines.

Near the climax of Halo: Combat Evolved, fear and desire turn monotonous. Combat turns predictable, and mechanical. Enemies move in robotic patterns, and die in the same stylized ways… punctuated by the same grisly, or comedic death animations. Curiosity rises in answer to the steady monotony of warfare.

Probing deep, venturing into the depths of the Halo ringworld, Master Chief begins to discover hints of an ancient struggle preceding human civilization. Mysteries are answered, and the resolution of every successive question prompts another three questions, another three unsolved mysteries. The story shifts from militaristic, hard sci-fi space opera, to the Biblical survival horror of the Flood skittering through damp, dark tunnels. Scattered muzzle flashes light the darkness, revealing an inexhaustible horde of parasitic alien zombies racing towards the player’s camera.

Long-form storytelling needs to rotate through various forms of emotional stimulation, like a roller-coaster.

Otherwise, hitting the same emotional note for an extended period of time will bring diminishing returns. At some point, audiences are simply exhausted by sorrow, or joy, or the thrill of vicarious power fantasies. Variety is crucial.

Now we return to the lessons of middle school English, or high school English. Conflict can be classified in terms of some basic elemental types: Man versus Man, Man versus Nature, Man versus Self, Man versus Society.

Very obvious material.

Quite boring.

Conflict can be layered into complex narratives by rotating through different types of challenges — various forms of problems. It’s a mistake to crowd a story with an excessive number of thinly-developed conflicts, and to split focus into a diffused array of inadequate problems, so that none of the threats resonate with the audience, and the hero’s motives feel weak and unconvincing. So one critical mistake is to split focus with too many subplots. But the opposite and more common mistake is to write a rigid, one-dimensional drama which feels monotonous because the main characters are only challenged in one or two dimensions, and therefore the danger never feels urgent, or intense.

Problems can be romantic… financial… emotional… social… medical… artistic… professional… egotistical… reputational… intellectual… spiritual… philosophical… problems arrive in many forms. Assaults hit from many angles, through many vectors. Physical survival is the most immediate form of conflict. It will always produce a reaction for a stranger to walk into the room and point a gun at the hero’s head. But actual violence, and physical survival, is the weakest form of character motivation in long-form writing. As soon as safety is achieved, violent danger becomes uninteresting. By itself, violence is dull and repetitive. It’s cool, but there needs to be something deeper.

Most stories take place on a minimum of three interconnected layers — physical, emotional, and spiritual/philosophical. Sometimes there’s a fourth layer, which is social/political. Sometimes there’s a fifth layer, which is a romantic/sexual tension. For whatever reason, this is usually the sequence in which storytellers invent, and then layer, their narrative conflicts.

To explain in more detailed terms:

1.) Physical conflict — Brute violence and survival.

2.) Emotional conflict — some kind of individual, internal character arc, during which the hero learns a relevant moral lesson and undergoes a dramatic, dynamic personal transformation over the course of the story.

3.) Spiritual/Philosophical conflict — frequently referred to as the story’s “theme”, or “message”. On a macroeconomic level, the Big Picture of the narrative informs us of the author’s implicit metaphysical worldview. Events are framed to suggest a moral argument, the creative intellectual tension of (usually) two or three adversarial points of view. Typically the hero undergoes a process of Thesis, Antithesis, Synthesis and starts with an internalized Deceit or Half-Truth which causes the character’s character flaw, then undergoes a transformative spiritual adventure which educates and sharpens the hero to realize a Deeper Truth, which leads to a Synthesis where the hero properly integrates his original flawed worldview (Thesis) with the villain’s mirrored, inverted, and equally flawed worldview (Antithesis), in order to arrive at a mature understanding of Light and Darkness, Morality and Sin (Synthesis), accepting and reconciling with the burdens of a Fallen World.

4.) Social/Political conflict — the hero’s individual struggle functions as a microcosm of a larger communal war, and his victory is leveraged into winning a parallel war for the overall tribe.

5.) Romantic/Sexual conflict — the hero, or heroine, undergoes a journey of self-discovery which makes them more attractive to the woman, or man of their dreams.

The immediate question posed by any story is: Who cares? Why should audiences root for this hero? Why does this story merit the focus and passion of strangers?

In the case of “Trap” (2024), the movie fails to answer this question. For the most part, with rare exceptions, stories are archetypal morality plays — they are religious sermons which feature three types of heroes: low-status underdogs, exhausted antiheroes, and monstrous villains. All of these characters represent a meditation upon the nature of power, and morality. The underdog lacks power, and his arc centers around courageous persistence to ascend his wretched circumstances. The antihero already possesses significant power as an elite player in his industry, community, or niche, but the antihero is exhausted with the ethical burdens of living in a Fallen World where undeserved tragedies oppress the weak. The antihero’s character arc can perhaps be framed as a romance, where a disillusioned champion rediscovers his appreciation for life, and falls back in love with his role in the community’s social fabric. The monstrous villain already has power, which he misuses and abuses. The villain is confronted with his sins, and is forced to either atone for his crimes, or to suffer a karmic tragedy, one way or another. Either the villain will repent and be redeemed, or he will be destroyed.

“Trap” (2024) is a cute little scenario. But it fails to communicate any reason why the audience should root for a remorseless, sadistic serial killer to escape from the police.

Why should audiences cheer the continued murder of random, innocent civilian victims?

In the Saw franchise, the gruesome torture chambers are ambiguously justified as the karmic retribution of a demented serial killer who intentionally confronts various forms of sinners and criminals with punishments that symbolically embody their own misdeeds.

No such justification, or rationalization, is presented on behalf of Cooper Adams. He has a daughter… but who cares? Plenty of monsters have kids. It doesn’t excuse their crimes.

Cooper Adams does not fit neatly into any of the three classic character types — a low-status underdog, an exhausted antihero, or a monstrous villain. The manpower and resources of the police blockade turn him into an underdog — but only in a physical sense, attempting to escape capture. He doesn’t share much in common with an antihero. Cooper Adams seems closest to a villain — but he’s never confronted with a chance to repent, which is a classic stage in the arc of a monster without a conscience.

The lack of a clear moral arc, or a character direction, is one of the underlying sources of the film’s confused, aimless plot, where exciting events are happening, but the suspense, tension, and adventure lacks logical consistency.

His plot twists are cheap gimmicks, which is fine, but they’re sudden and random, rather than being elegant and inevitable… based on subtle groundwork prepping the big reveal.

In the first fifteen minutes of the movie, M. Night Shyamalan should’ve introduced an internal emotional wound, some kind of unresolved problem, need, or desire that was troubling Cooper Adams. His focus on the intriguing scenario — a police ambush and a criminal rampage occurring at a music concert — caused him to overlook the emotional aspect of the narrative. There’s a saying, “If you have a problem in the Third Act of your movie, the source of the problem is in the First Act of your movie.” In plain English, if your story’s climax doesn’t resonate with audiences, the most common cause of the problem is a lack of subtle, intentional preparation laying the groundwork at the beginning of the narrative. Lack of setup, and insufficient foreshadowing, results in an ending that feels forced and unnatural — a Deux Ex Machina.

Instead of building a flawed, sympathetic character at the start of the film, M. Night Shyamalan relies upon camerawork to orient the audience on the desired character viewpoint. In fairness, his cinematography is correct and well-executed. His camera is used competently; the problem is the screenplay.

Audiences will naturally, reflexively identify with anyone or anything that the camera follows. Pixar movies feature robots, talking animals, anthropomorphic fish and rats and dogs — the focus of a camera sparks the onset of a beautiful connection. But it’s not enough by itself. An emotional scaffold must be built atop the mechanical, technical focus on a lead character.

Christopher Nolan comments upon the empathetic connection between audiences, and anyone a camera follows for a significant period of time:

Tom Shone, The Nolan Variations:

“Toward the end of his first year at UCL, his father bought him a copy of Jon Boorstin’s The Hollywood Eye (1990), a book exploring the various connections — visceral, vicarious, voyeuristic — between movies and their audiences. The associate producer of All the President’s Men, who had gone on to direct a number of Oscar-nominated science and nature documentaries, Boorstin had much to say about several things close to Nolan’s heart, including the slit-scan photography developed by Stanley Kubrick for 2001: A Space Odyssey (“as close as anyone has come to the distilled sensation of pure speed”), the format of IMAX (“the closest we’ve come to pure movie”), and the editing of the shower sequence in Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), and more particularly the cleanup Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) performs afterward. Bates’s horror mirrors our own, Boorstin wrote:

“Ever the dutiful son he now mops up the mayhem to protect his “mother” (though the poor fellow is in such a state of shock he never takes off his suit jacket for the messy work). Perkins not only earns our sympathy by sharing our horror, he earns our respect for his stoic bravery and resourcefulness. It is hard to remember the first release of the film when we didn’t know Perkins himself was the killer, but such is the strength of the sequence that even after we know the truth our heart goes out to poor Norman Bates. Finally, Perkins pushes Leigh’s car into the swamp with her body in the trunk. For a few agonizing seconds the car won’t sink. We see the panic and desperation in Perkins’ face; in an astonishing switch we find ourselves actually rooting for the car to disappear. Hitchcock has turned us so far around that five minutes after we’ve seen his star brutally murdered he has us cheering for a man to hide her body… this vicious sleight of hand, more than the shower sequence, is the true tour de force of Psycho.”

—Jon Boorstin, The Hollywood Eye

The observation struck deeply with Nolan.

“It’s the most incredible thing, what Hitchcock’s done; he’s taken our point of view and flipped it,” he says. “How has he done that? Simply by showing you and making you complicit in the difficulty of the task of cleaning up. I think for me, Psycho’s probably the Hitchcock film that’s the most beautiful, photographically. If you took any frames from Psycho, they would be immediately striking. I mean, Vertigo has cinematic beauty, obviously, but it’s not pretty, but in Psycho, you had that beautiful closeup of Norman Bates’s eye; that was the thing I remember from that, just looking through the peephole. It’s kind of exquisite. Everything you do as a filmmaker is about point of view. Where you put the camera. It’s the process I am going through as a filmmaker. When I am deciding how to shoot something on the day, whose point of view is it? Where do I want the cameras? It’s always that. The conventions have changed over time, but filmmakers have all wrestled with the same essential trick of geometry. That is why first-person movies so rarely work. You’d think maybe it would remove the camera, but if you watch The Lady in the Lake, with Robert Montgomery as Marlowe, it’s all shot from his point of view. You only see him in mirrors — they punch the camera in the face; he kisses the girl. It’s a fascinating experiment.”

—Tom Shone, The Nolan Variations

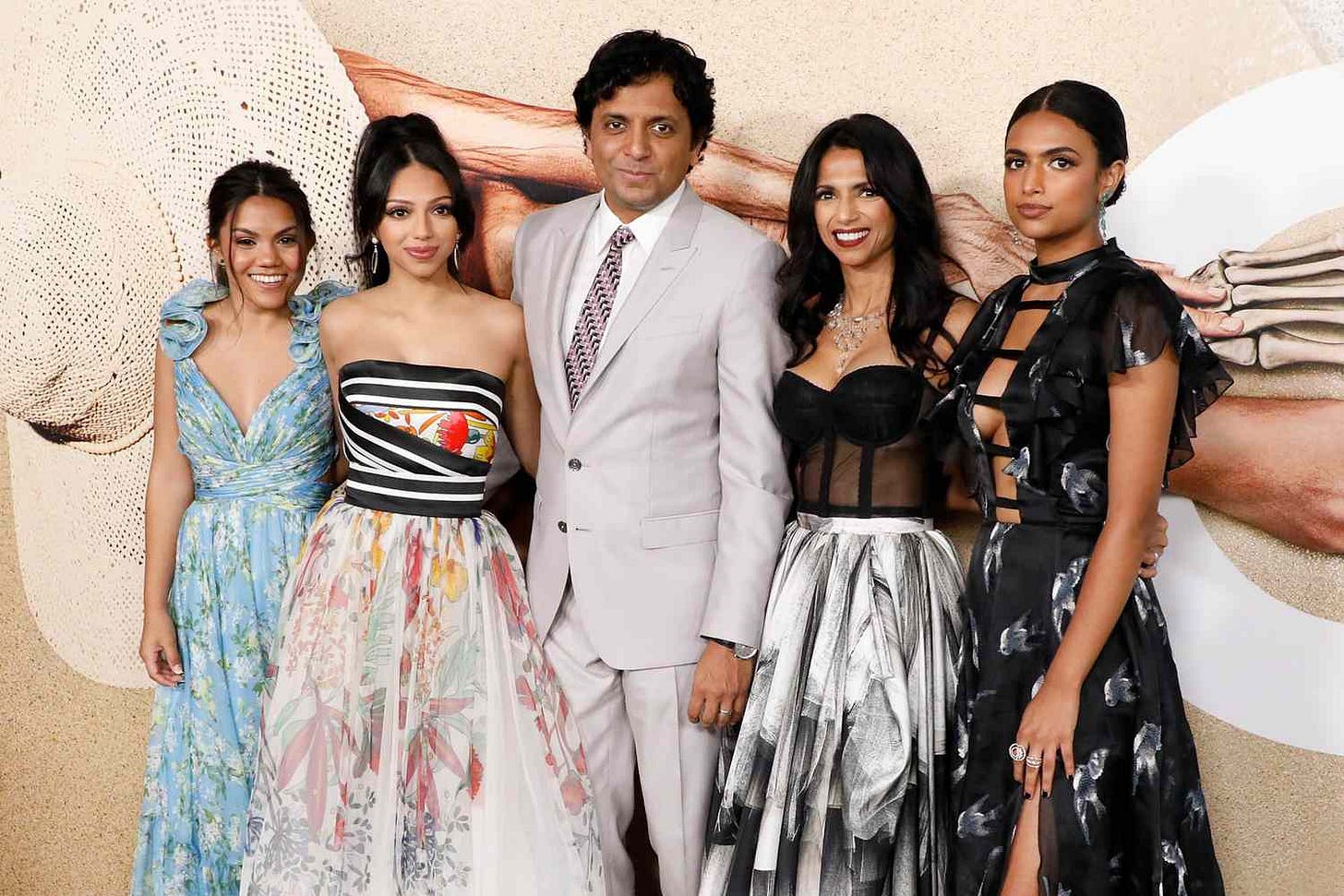

Weirdly, this serial killer adventure appears to be one of M. Night Shyamalan’s most personal films. The story is allegorical, and autobiographical.

Beneath the gruesome and fast-paced murders, there’s a profound depth of poignancy, and sentimentality. The thematic core of the film is an anguished exploration of what it means to be a father, and husband. The visual and physical layers of the movie, where a police manhunt drives a stressed serial killer to take drastic countermeasures, is awkwardly and unsuccessfully tethered to a more subtle, patient family drama, where a man experiences life as a helpless spectator unable to solve the emotional turmoil of a household of women.

In real life, M. Night Shyamalan has a wife and three daughters. They’re beautiful. And quite a handful of emotions.

He’s outnumbered!

There may be a slight excess of estrogen in the Shyamalan family.

There’s an intelligent movie concealed beneath the superficial tension of a serial killer eluding a police blockade with ostentatious, self-defeating crimes.

The horror film’s kinetic, dangerous A-story centers around a police blockade at a crowded music concert. The movie’s emotional, thematic B-story introduces an awkward father who loves his teenage daughter, and her covert female intrasexual competition with meanspirited middle school girls who are conspiring to exclude her from their selfies on social media.

In metaphorical terms, “Trap” (2024) is an exploration of the burdens, responsibilities, and loneliness of masculinity. It’s a meditation upon the obligations of being a husband and father, and recognizing the emotional disconnect between a responsible man and the family he provides for. Cooper Adams wrestles with doubts, problems, rivals which his wife and daughter are never aware of. He shelters their innocence by never confiding in them about his problems.

This appears to be a symbolic expression of M. Night Shyamalan’s family dynamic, and his lonely experience as a high-earning cinematic auteur: film negotiations can drag on for years. After every movie finishes, a director or actor is functionally unemployed… until the next temporary, freelance project appears. The money is lucrative. But there is never any job security in the volatile Hollywood ecosystem. Stars rise and fall, with meteoric velocity. Fame sparkles and dims. Celebrity disappears in the morning, like fairy gold.

Part of being a loving father is that M. Night Shyamalan takes on all of these worries, and does his best to never share them with his wife or kids.

I’m speculating here — the exploration of a husband and father’s loneliness seems to be the thematic undercurrent expressed by the film. But again, the symbolism is never properly articulated, and the movie’s philosophical undercurrent never achieves a graceful, elegant unity with the physical dangers and concrete dramatic struggle playing out onscreen.

And on a deeper level, the wife’s betrayal of her murderous, sadistic husband embodies an insecurity hidden in M. Night Shyamalan himself — how much does his wife really support him? How much does she love him? If he tested her loyalty, how far would it go?

Phrased another way, the teasing female question, “Would you love me if I was a worm?” finds its romantic male equivalent “Darling, would you still love me if I was a notorious serial killer?” 🙈 🙈 🙈

Apparently, the answer is no.

Or so he fears.

At the beginning of the movie, the daughter’s social life is established as the father’s main problem — his daughter is being ostracized by her friends at school, and is no longer invited to poast on social media, although she sees selfies and video dances being uploaded by all the other Zoomer girls. There’s a key conversation where Cooper Adams asks his twelve-year-old daughter Riley about the problems of her social life:

Cooper Adams: “So, give me the update. What’s going on with those girls at school?”

Riley: “It’s fine.”

CA: “It’s fine?”

Riley: “I don’t really want to talk about it.”

…

[later in the stadium’s halls]

Riley: “They aren’t mean anymore. They just don’t include me. And they keep posting stuff together.”

CA: “I see… It must be hard seeing what everyone else is doing all the time. Your generation is so connected, even when you’re not that close. Why don’t you and I take a picture together when we go inside? You and your dad. Your friends will be so jelly.”

Riley: “That would be like the worst idea. And don’t say jelly, dad.”

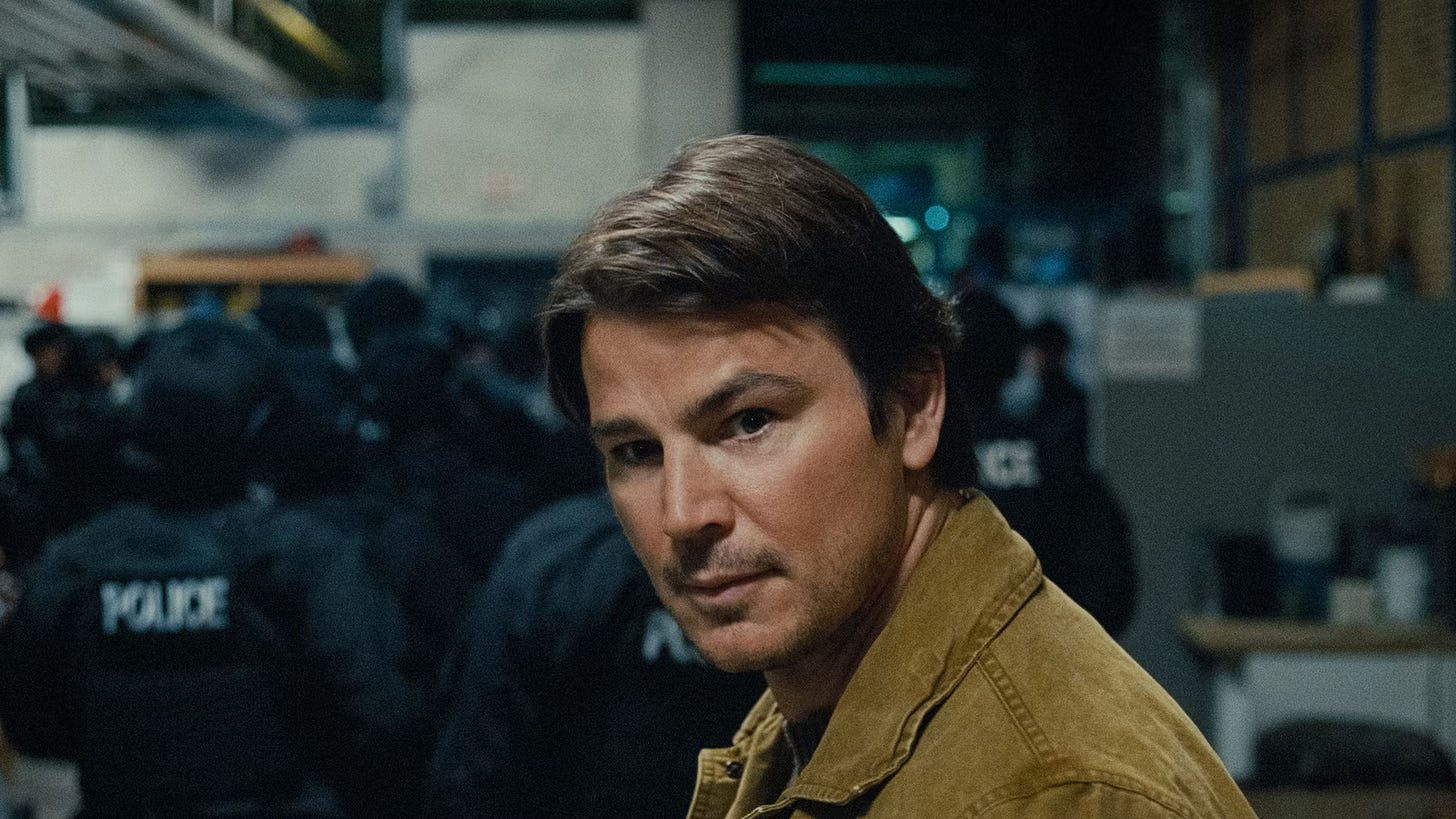

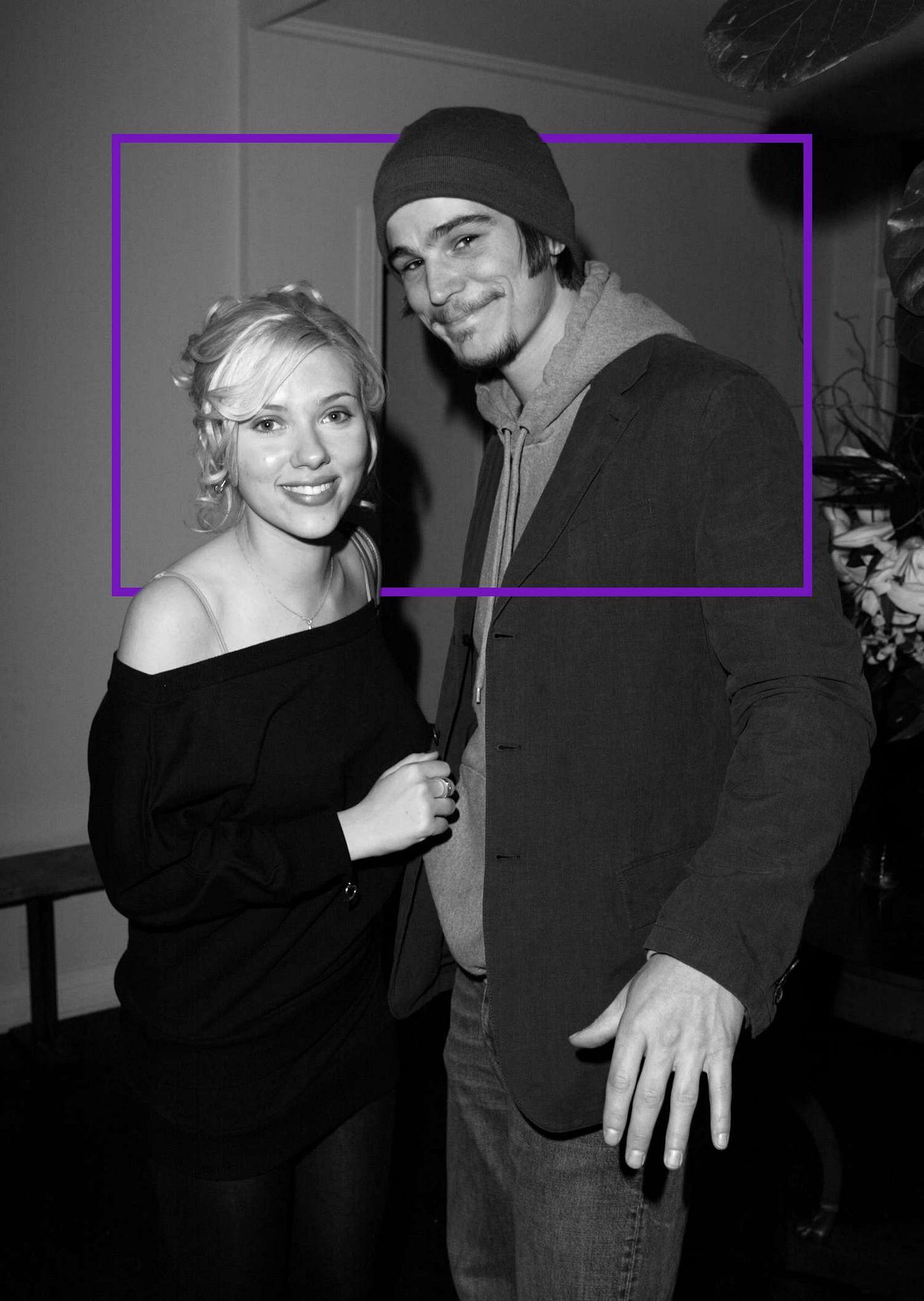

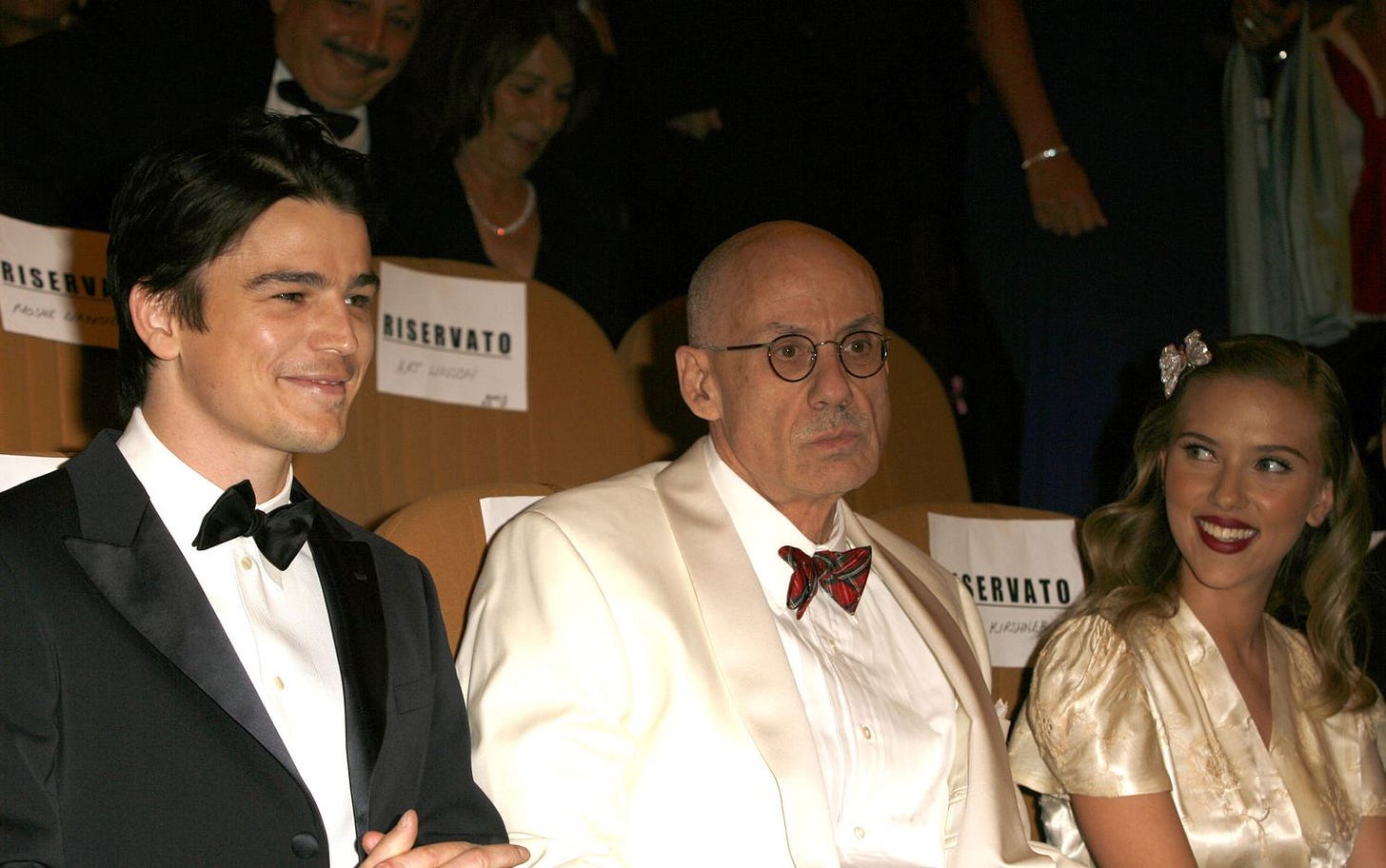

Part of what makes this allegory obvious, the fact that M. Night Shyamalan is venting some kind of personal anxiety through the horror medium, are the physical mannerisms of Josh Hartnett, the actor playing the elusive and remorseless criminal Cooper Adams. In this movie, Josh Hartnett is a lame, overenthusiastic dad seen as Cringe and majorly uncool by his daughter. A roman à clef, presenting M. Night Shyamalan’s family dynamics beneath a thinly-disguised veneer. But in real life, and during his previous films, Josh Hartnett has always been a suave, soulful heartthrob — 6’3”, handsome, a leading man previously considered and rejected for the role of Batman in Batman Begins (2005), and the former longtime boyfriend of Scarlett Johanssen when she was at the beginning of her career (2005-2007).

Josh Hartnett has always been a sensitive, emotional, intensely brooding figure who is deeply concerned with his acting career, and about how to project himself on the screen. Nothing like the affectionate, goofy, and socially awkward father he played in this movie.

At the end of the film, Riley discovers her father is a notorious murderer — but she comes to terms with this hideous truth, and declares her love for her father, while the police handcuff and lead him away into the back of a van.

It’s an ineffective, but sweet ending, which seems to communicate M. Night Shyamalan’s hope that his daughters would love and accept him if they ever saw him for the flawed, imperfect, but devoted father and husband he is.

One thing that I think is a little bit unfair, but merits examination, is the central role of M. Night Shyamalan’s real-life daughter in this film.

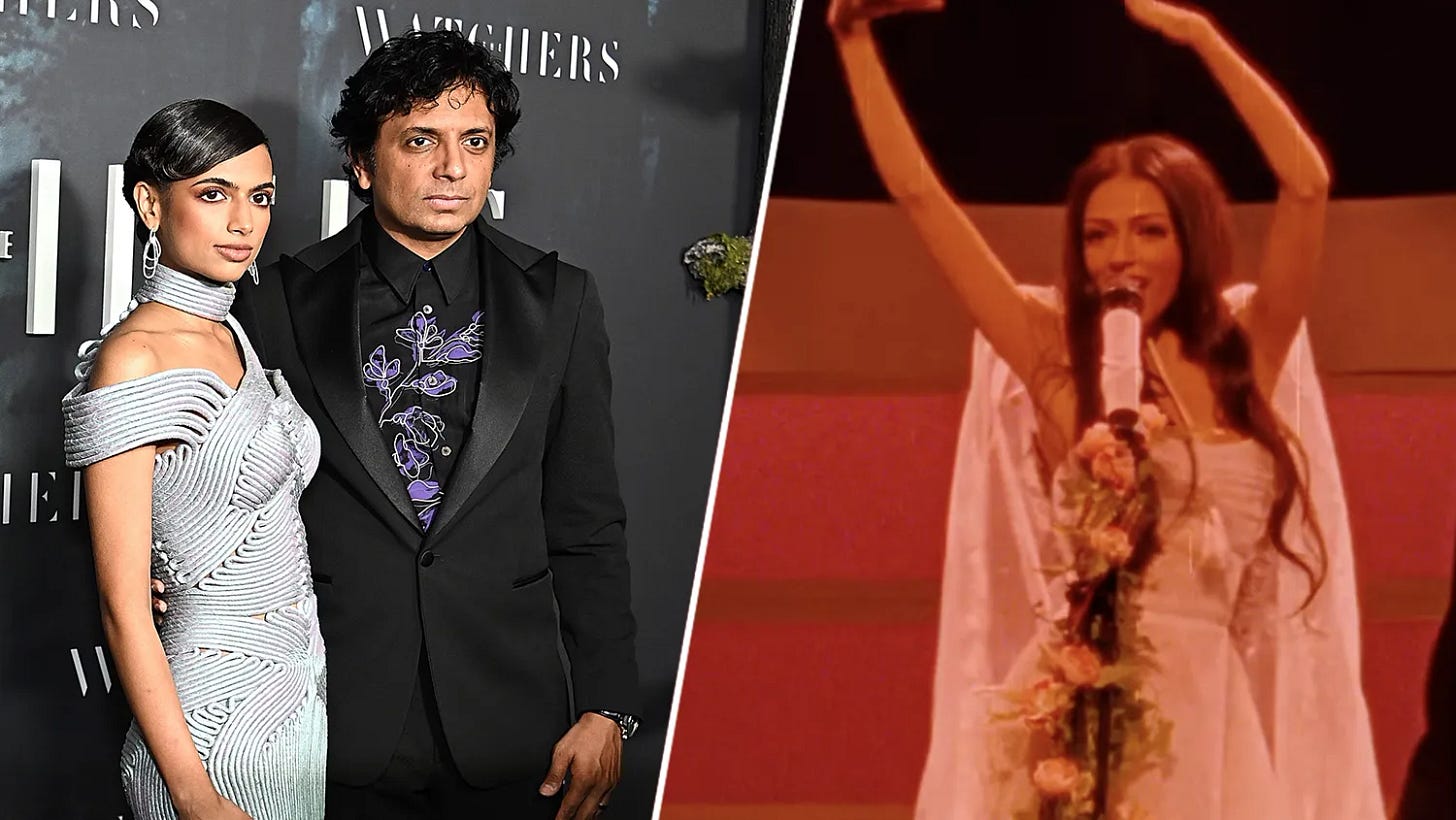

Saleka Shyamalan was cast in “Trap” (2024) as an iconic pop singer named Lady Raven, a global sensation in the style of Taylor Swift, Selena Gomez, Olivia Rodrigo, Ariana Grande, or a similar archetypal cultural touchstone.

Almost every scene features Saleka performing in the background, and later the plot is railroaded into some implausible directions, shoehorning the singer Lady Raven into a direct confrontation where she is kidnapped by the deranged, gleeful Cooper Adams.

This horror film, entrapped at a music concert, mostly exists as a way for M. Night Shyamalan to showcase his daughter’s musical ability, and potentially launch her career as a singer. Last year Saleka released her debut album Seance (2023), and Saleka Shyamalan’s music has been featured in three of her father’s projects: Old (2021), Trap (2024), and Servant (2019-2023).

M. Night Shyamalan declares:

“I directed an entire concert! And it wasn’t just a thing in the background. It’s equally important. There is no pretend concert going on. I love the idea of cinema as windows within windows. One of the reasons to come see the movie at the movie theatre is because there’s literally a real concert that you can see nowhere except in that movie.”

—M. Night Shyamalan

How do I phrase this diplomatically?

Her music is not very good.

It’s bland, vapid pop which lacks any sort of edge, or substance, or message, or differentiated sensibility. There’s no identity, and no purpose to the songs, other than the vague echoes of a generic longing for popular acclaim.

There are some beautiful, stylish moments oriented around the iconography of the singer Lady Raven. Glimpsed from a distance, Lady Raven steps out of a van and is greeted by a throng of cheering, screaming fans, and she offers a friendly wave in their direction — which feels like the authentic gesture of a global celebrity. It’s modest, understated, and subtly conveys the sensation of a woman besieged by constant external demands, but who nevertheless retains a sense of gratitude for her supporters. There are posters and T-shirts with Saleka’s face emblazoned across the canvas. Radios and speakers play her songs, like ambient noise in the background of scenes. She dances on miniature television screens in the background of mundane conversations, and it seems utterly convincing that Lady Raven is some kind of charismatic musician beloved by teenage girls.

The idea of Lady Raven succeeds in the background of the film, confined to the boundaries of the narrative.

She doesn’t work in the foreground.

Celebrity gravitas is a real phenomenon; charisma is cultivated over time. There’s an artful methodology to crafting a media persona, and performing in front of mass audiences as a cultural icon.

I blame M. Night Shyamalan for putting his daughter in a situation where she is supposed to seem like some kind of mythic cultural presence, radiating charisma, when in fact she is exactly what she is supposed to be at this age — an ordinary (although beautiful) girl who is ambitious and passionate about music.

On one hand, this is really cool for a father to love his daughter so much that he designs a big-budget film around promoting her nascent career as a musician, and casts his daughter as one of the lead roles. It’s a profound act of love, empowering and supporting his daughter to an incredible extent, and really going a step beyond ordinary fatherly encouragement.

On the other hand, it’s professional negligence for M. Night Shyamalan to confuse his subjective passion for an idea with the dualistic role of objective self-criticism of the purely technical merits of aesthetic quality. Don’t get high on your own supply. First drafts are about passion, second drafts emphasize polish. A cool idea demands fluid implementation.

It doesn’t hold up to scrutiny.

When Saleka Shyamalan steps onto the stage, she does not radiate the confidence and prestige of an icon… Taylor Swift, Ed Sheeran, Elton John, Adam Levine, Beyonce, Kanye West, Elvis Presley, Justin Bieber, Ariana Grande, Celine Dion, Paul McCartney.

In fairness, almost nobody does. And I think it’s unrealistic to expect that kind of outsized charisma from an ordinary young girl, especially at the start of her career. But according to the movie, Saleka Shyamalan is one of the most famous musicians in the world, long-accustomed to performing in front of crowds, and has sold out multiple concerts in the same day.

From a distance, Lady Raven seems real and intriguing.

When the camera zooms in, Lady Raven seems fake and the verisimilitude of the movie begins to crumble, jeopardizing the audience’s suspension of disbelief.

This is really not because Saleka Shyamalan is doing anything wrong.

Trap (2024) is a musical, and the music is bad.

It’s not bad in an ironic, self-aware, metafictional way, where the anemic, tame songs are commenting upon the commercialized emptiness of mainstream pop music in order to advance some kind of detached intellectual critique of the relationship between audiences and performers in a media-driven, and social media-fueled epoch of viral content and celebrity marketing — where some kind of intelligent repackaging of Marshall McLuhan’s insights is being conveyed.

The music is simply mediocre. Not terrible. But not emotionally evocative on any level.

It’s a big risk to feature this much music in a horror film.

The music is central to the film’s primary value proposition.

And I feel guilty about attacking M. Night Shyamalan’s daughter in such acerbic detail, or tearing into a pretty young girl with a cool dream and the confidence to put herself out there and take an audacious risk.

But the problem is, this film has roughly the same amount of music as The Phantom of the Opera. And the concert’s quality is not remotely in the same ballpark as the compositions of Andrew Lloyd Webber.

It’s an intentional choice to zoom in on the weakest segment of the film, and to keep the camera fixated on this weakest point for close to an hour. A lot of thought went into this approach. But it was the wrong decision.

Saleka Shyamalan is a much better dancer than singer — she’s able to do some graceful, sinuous moves with her arms. It’s obvious she’s had formal training, in both dancing and singing. She has a pretty voice. But the melodies themselves were unremarkable. And I think the real mistake here is to prematurely spotlight a young, developing talent and to place the burden of excessively heavy expectations onto an ordinary girl.

There’s a paradox here, in that nobody will give you your shot in life. Anything you want, you need to want desperately and ferociously enough to Carpe Diem; to get out and chase it and seize it and tear out the competition’s throat.

Some level of aggression and audacity is necessary to triumph in an extremely competitive industry at the highest levels. Talent alone is rarely, if ever, enough.

So if you’re too patient in development, and you wait too long for a golden opportunity, then the moment will never arrive, your whole life can slip away, and at the end of your life you might still be wondering what happened… How did it all go wrong?

But on the other hand, prematurely taking on too much responsibility, and stepping into the breach of an enormous task, leads to crushing failure.

Trap (2024) would’ve been a more effective, elegant film if two-thirds of the music had been cut from the final version of the movie, and if Saleka Shyamalan had been mostly glimpsed from a distance, functioning as a sort of cipher. From a distance, Saleka would have retained her glamorous celebrity mystique, and the audience would’ve projected their own romantic delusions onto her, wondering who she was, and what secrets she was hiding. Up close, she was revealed to be a boring, ordinary human girl with the same kind of emotions and desires and flaws as any other person.

Gorgeous art is created with curiosity, sincerity, relentless energy, and meticulous attention to tiny details which other people would consider unimportant.

Nobody considers M. Night Shyamalan’s horror films to be “high art”, or “serious intellectual cinema”. But he demonstrates the passion of a fanboy, the marketing and negotiation savvy of a consummate business mogul, and the uneven technical craftsmanship of a talented amateur. It’s intriguing that M. Night Shyamalan could become one of the world’s most profitable directors while committing so many basic narrative mistakes. Especially because these errors are mostly easy to correct, but nobody has been correcting them at any point in the past twenty years.

Success is like that; sometimes it’s ugly, but if it’s good enough to get the job done, that’s all that matters.

There are tens of thousands of high school teachers and college professors with an unfinished manuscript buried in their cabinet drawer, who can recite many of the aesthetic fundamentals listed in this film review. And yet, M. Night Shyamalan has surpassed them by actually getting out there into the field, taking big risks, investing his career and life and passion, and simply making films he believed in.

So there always needs to be a bias towards action, at the expense of abstract theory — winning matters more than theoretically knowing the right answer to the test.

I wrote this review to demonstrate the sort of aesthetic thought process which should guide any artistic endeavor. Every detail deserves consideration. Every detail must serve the larger whole. Individual impulses must be sacrificed in pursuit of the end result. All of us are human, and sometimes we will make the wrong decisions, but our mistakes need to happen for the right reasons, based on an intelligent, passionate, ruthless process of artistic creation.