Theodore Kaczynski, Industrial Society and Its Future:

“A technological advance that appears not to threaten freedom often turns out to threaten it very seriously later on.

For example, consider motorized transport.

A walking man formerly could go where he pleased, go at his own pace without observing any traffic regulations, and was independent of technological support-systems. When motor vehicles were introduced they appeared to increase man’s freedom. They took no freedom away from the walking man, no one had to have an automobile if he didn’t want one, and anyone who did choose to buy an automobile could travel much faster and farther than a walking man. But the introduction of motorized transport soon changed society in such a way as to restrict greatly man’s freedom of locomotion.

When automobiles became numerous, it became necessary to regulate their use extensively. In a car, especially in densely populated areas, one cannot just go where one likes at one’s own pace; one’s movement is governed by the flow of traffic and by various traffic laws. One is tied down by various obligations: license requirements, driver test, renewing registration, insurance, maintenance required for safety, monthly payments on purchase price.

Moreover, the use of motorized transport is no longer optional.

Since the introduction of motorized transport, the arrangement of our cities has changed in such a way that the majority of people no longer live within walking distance of their place of employment, shopping areas and recreational opportunities, so that they have to depend on the automobile for transportation. Or else they must use public transportation, in which case they have even less control over their own movement than when driving a car. Even the walker’s freedom is now greatly restricted. In the city he continually has to stop to wait for traffic lights that are designed mainly to serve auto traffic. In the country, motor traffic makes it dangerous and unpleasant to walk along the highway.

(Note this important point that we have just illustrated with the case of motorized transport: When a new item of technology is introduced as an option that an individual can accept or not as he chooses, it does not necessarily remain optional. In many cases the new technology changes society in such a way that people eventually find themselves forced to use it.)”

—Theodore Kaczynski, Industrial Society and Its Future

To get away from the modern world, you would need to travel to someplace like North Sentinel Island, located in the waters of the Bay of Bengal, several hundred miles off the coast of India, Burma, and Thailand. You could hide out among an indigenous tribe that’s rejected all foreign human contact — if the tribe's barbarians would accept you, which obviously isn't something they do for anyone. Maybe you could build a secret base somewhere in the Amazon rainforest. Other than that, technology and its consequences are everywhere. There’s no escape.

Civilization is an engine.

It’s a machine.

For the most part, modern technology, sanitation, and infrastructure provide miracles that have become mundane facts. Babies survive childhood diseases. Antibiotics have replaced amputations. Plumbing and air conditioning make life comfortable. Dentistry produces beautiful smiles. People from a thousand years ago would be astonished by cars, computers, satellites, airplanes, submarines, scuba diving. Technology solves more problems than it creates, delivering win-win interactions, multiplying the productivity of individual genius and ordinary labor, so that on the whole the convenience, prosperity, connection, and security delivered by innovation outweigh the negative externalities — and there are a lot of negative externalities.

The flipside is technological dependence.

Life transforms, society transforms, based on the powers of technology, into an arrangement that would be impossible to sustain without technology. Everyone is born hooked into that tech-structured society; hooked into a subtle, familiar matrix of technological dependence.

Chemical fertilizer improves crop outputs. In response, industrial populations grow to a massive size which is impossible to sustain without the same inputs of chemical fertilizer. Most technological innovation which seems entirely positive-sum has the same long-term effect of restructuring society in remarkably intractable directions, because what incrementally emerges as cultural and behavioral architecture is embedded in the technology itself.

Any alternative fades away.

After two or three generations, structural changes to a society crowd out niche options. As a result of network effects and scale economies, the default option becomes the only option.

This is where the pain begins — the switching costs associated with leaving a networked scale economy.

Christian Heiens, May 29th, 2025:

“The fiat monetary system is structurally committed to infinite inflation and debt expansion. The whole thing is on autopilot because there isn’t a viable alternative to the status quo without inducing some sort of economic catastrophe.

Don’t believe me?

Tell me if you think any of these five things will change any time soon.

1) Exponential debt has to be endlessly rolled over to avoid mass bankruptcies.

2) Productivity growth can no longer keep up with debt obligations (some think AI can solve this, but so far this remains a fantasy).

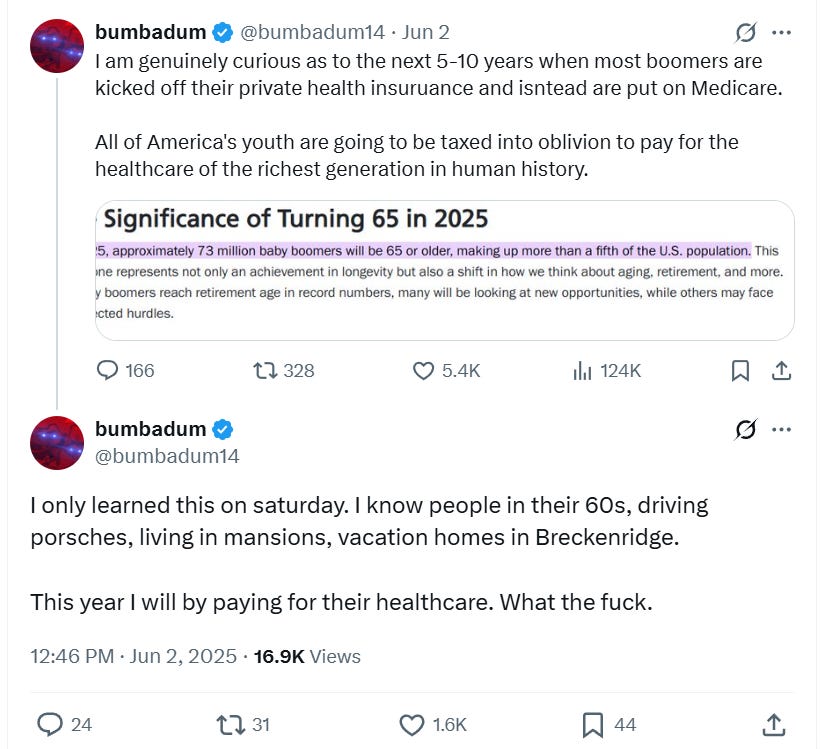

3) Boomers will continue to demand more entitlement spending.

4) Politicians will always choose inflation over austerity.

5) Central banks are trapped by decades of low rates and QE, and are unable to stop without triggering a deflationary spiral.

As long as these five things remain true, then Lyn Alden is not wrong when she says “nothing stops this train.””

—Christian Heiens, May 29th, 2025:

The utility of a network economy allows for a shared currency, a standardized form of monetary exchange.

Everyone is plugged into the same machine. All the tribe’s members are paid in a legible currency. Tasks soon drift into two overlapping purposes:

1.) To create value

2.) To capture value

Over time, relationships mutate into a parasitic equilibrium. Labor is downstream of resource distribution, and ordinary members of civilization are dependent upon collective goods they can no longer provide for themselves — medicine, sanitation, electricity, WiFi, gasoline. Technology creates complex products that require international supply chains and corporate manpower to design, assemble, and deliver. Even a simple pencil, as often quoted by Milton Friedman and immortalized in Leonard Read’s famous essay “I, Pencil”, requires numerous components (cedar, lacquer, graphite, ferrule, factice, pumice, wax, glue), expensive factories, specialized labor, and advanced transportation to deliver to ordinary consumers.

In the worst-case scenario, citizens are held hostage to a negative-sum dollar economy, trapped in a decaying network that doesn’t listen to their individual voice and doesn’t allow a peaceful exit from tyranny.

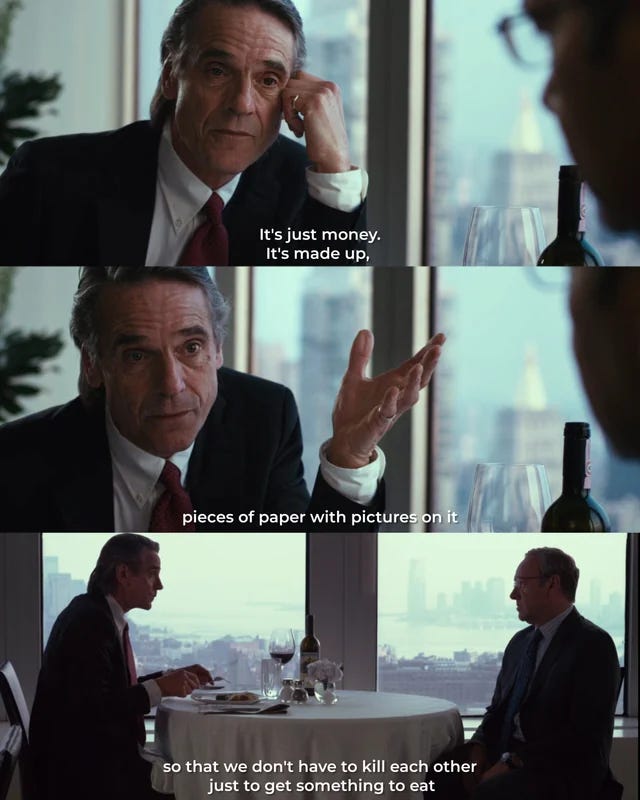

J. C. Chandor, Margin Call:

“Jesus, when did you start feeling so sorry for yourself, it's unbearable... What, you think we may have helped put some people out of business today? That it's all just for naught?

Well you've been doing that every day for almost forty years Sam. And if all this is for naught, then so is everything else out there.

It's just money, it's made up, a piece of paper with some pictures on it so we don't all kill each other trying to get something to eat.

But it's not wrong and it's certainly not any different today than it's ever been. Ever. 1637, 1797, 1819, `37, `57,`84, 1901, `07, 1929, `37, `73, and 1987... God damn did that motherfucker fuck me up good, 92, 97, 2000, and whatever this is gonna be called.

They're just the same thing over and over.

We can't help ourselves, and you and I can't control it, stop it, slow it, or even ever so slightly alter it... We just react... and we get paid well for it if we're right... and get left by the side of the road if we're wrong. There's always been and there's always gonna be the same percentage of winners and losers, happy fucks and sad sacks, fat pigs and starving dogs in this world... yes there may be more of us today... but the percentages... they always stay exactly the same.

—J. C. Chandor, Margin Call

In the best-case scenario, civilization allows ordinary people to triple their expected lifespan, while living in a sprawling urban fortress defined by comfort, security, and shared community which would otherwise be impossible.

It’s important to understand how this unspoken macroeconomic reality shapes the mindset of society’s participants. The architecture of civilization sets the pathway for behavior, and communal beliefs. On a subconscious level, people realize they are dependent on a system they do not control, plugged into a network as one tiny constituent of a vast industrial machine, rewarded or punished by what are often arbitrary rules, paid with arbitrary tokens that dilute over time.

As long as the system mostly works for its loyal residents, most of the time, happy citizens are willing to turn a blind eye towards all manner of injustices. There will always be problems in any civilization, and safe inhabitants are blasé towards the suffering of fringe members. Patriots want the system to continue to function as usual, without disruptions. Comfortable people intensely dislike any kind of potential discomfort that might be imposed upon them, even minor short-term pain offered by ambitious reforms — so that even when everyone admits that a systemic problem exists and needs to be fixed (such as a bankrupt pension system), the usual equilibrium is that nobody adjacent to authority is willing to risk their own comfort to solve entrenched problems, and anyone willing to implement radical solutions is kept far away from the levers of power.

As a corollary to this observation, a permanent underclass of professional malcontents tends to accumulate along the sleazy underbelly of any large society, marketing themselves as a solution to the long-neglected problems of the bottom rung of civilization. Even when civilization is providing a safe, prosperous life to 95% of its members, a revolutionary sentiment will usually begin to percolate and fester among the other 5%. A dangerous, resentful underclass tends to form over time. Sometimes they’re even correct about the problems of the industrial machine they are trapped inside.

Much of political theory is words, words, words that boils down to where people see their own position inside the machine.

Does the machine work for them? Then they probably want the status quo to continue without any change, until it breaks down at some distant future point, and the consequences implode in the laps of unborn future generations.

Does the machine overlook and neglect someone? Okay, we’ve identified a potential rebel. One malcontent, by himself, is powerless. But in large numbers, they reach a critical mass, and become an existential threat to the continuation of the social project as a whole.

tantum Quaslacrimas, June 7th 2025:

“Since trickle-down-economics is a pejorative term, it's worth rehearsing what it actually means: politicians might *think* they some economic policy is better for workers or the middle class or whatever, but (with one exception!) there is basically no evidence of any economic policy affecting relative distribution of income at the national level.

So the only kind of economic policy that makes people better off is the one that increases production, because if it doubles the size of the pie without changing the slice, everyone's slice doubles.

The term "trickle-down economics" just *assumes* that when politicians and bureaucrats think they know who a policy benefits, that must be who it actually benefits, and somehow mysteriously those benefits always "trickle down" to everyone else.

But that's not really what's going on; what's going on is politicians have no freaking idea, and if a change like deregulation is good for business, the immediate beneficiaries of the reform are going to bid up everyone else's wages and prices as well, so benefits from good policy end up being pretty widely-shared, and the doubling-time of national GDP growth always dominates every other consideration.

There is only one policy that changes the relative "slice" of the national pie each class gets, and that is mass immigration to batter down wages.

That's the one big exception to this rule, and boy have we learned that the hard way.

From a pure economic theory perspective it's obvious that you can't have a fixed relative division of slices of the economic "pie" with mass migration, because firms have more workers fighting for jobs but the same pool of capital. It's the exact inverse of the situation when a third-world country opens up its markets to foreign investment, so local interest rates drop and wages rise as new foreign-backed projects put people to work.

Some economists have denied this for the stupidest reason possible: obviously immigrants will (all else equal) go to where growth is fastest and wages are highest, rather than depressed backwater areas. "Wow, the places where the immigrants go are boomtowns!"

At the same time they deny that a larger pool of labor bids down wages, they also claim to be absolutely befuddled, totally gobsmacked, by the persistent and novel decline in US labor mobility since 1980.

In other words, it used to be that Americans in poor areas would go to booming areas in search of better jobs: sometimes, whole regions would move, like when Appalachia colonized the Rust Belt, or the Okies evacuated to California.

Now Americans move to the new boomtowns (the places where the new immigrants all want to be) less and less, and they stay in declining regions more and more, and it's a big mystery, no one can figure it out!”

—tantum Quaslacrimas, June 7th 2025

Civilization is a machine.

The machine’s benefits are real. But how benefits are assigned often seems arbitrary.

At worst, productive people are punished, while parasites are rewarded.

Social rank determines access to resources.

Tests, exams, credentials, medals, certifications exist to gatekeep the measurements that determine social rank. And in a corrupt society, everyone is trying to game the selection filters, because they lose faith in the ability of talent and integrity to naturally rise through the social hierarchy. Worse, a widespread (and justified) belief develops that the bottom rungs of society will be permanently abandoned to fend for themselves.

Walter Kirn, May 28th, 2025:

“The defining American industry of recent times has been the manufacture of licenses, certificates, franchises, memberships, rankings, and degrees. They are, like our money, produced by fiat, finally, ostensibly for the benefit of all but inarguably for the benefit of the issuers, whose cultish formulas and procedures are invaluable, closely-guarded assets, able to conjure wealth almost at will.

Now these "status factories," as one might call them, are being inspected, audited, and questioned in ways that their owners, managers, and benefactors — by far the largest group, which includes so many of us find outrageous, impudent, ominous.

The people at the top are rising up.

Against what, though? They sit on the thrones. They make the crowns.

To finesse this absurdity, they've decided to recruit the less privileged to their cause and to style themselves as tribunes of the marginalized.

But will the low agree to serve the high as moral and political shields? Will outsiders carry the banners of the insiders? And for what price, if so? Or is this a game they've played and lost before and know to be wary of in its latest form? For me, it's question of the moment as the "downrising" of the high-status class heats up. Or grows cold and flops.”

—Walter Kirn, May 28th, 2025

The Dissident Writer, May 28th, 2025:

“The foreign student issue is a great example of the parasitical nature of the regime. These universities were created as a public good for the people of the states in which they were located.

Public universities are part of our social capital.

The selling of seats to foreigners is a way for the people running these public institutions to profit off the social capital, while passing the cost onto the people through higher tuitions and the student loan rackets.

Think about the immorality of it. The people fighting to retain foreign students are literally fighting to impoverish your children. They want to saddle your children with debt so they can profit from a system that you support with your taxes.

When you look at our university system, you can see the evil that lies at the heart of our ruling class. Everything about it is designed to harm heritage Americans. You get the sense that the profit is just a bonus for them.”

—The Dissident Writer, May 28th, 2025

When things start to turn bad, really bad, a peculiar attitude of stubbornness spreads like a contagion among a society’s governing caste. It’s a belligerent attitude, where people who are already successful do their best to pull the ladder up behind them, and do their best to kick down ambitious younger generations trying to “pull themselves up by their bootstraps”. Scarcity generates hostility. In an ecosystem troubled by limited resources, shrinking opportunities, and social instability, new moral justifications emerge that “the poor deserve to suffer”. The fundamental problem is a game of musical chairs, with not enough opportunity to go around. Competitive moats are erected, byzantine barriers to entry disguised by opaque layers of bureaucracy and misdirection, in order to protect the Have-Yachts from the Have-Nots.

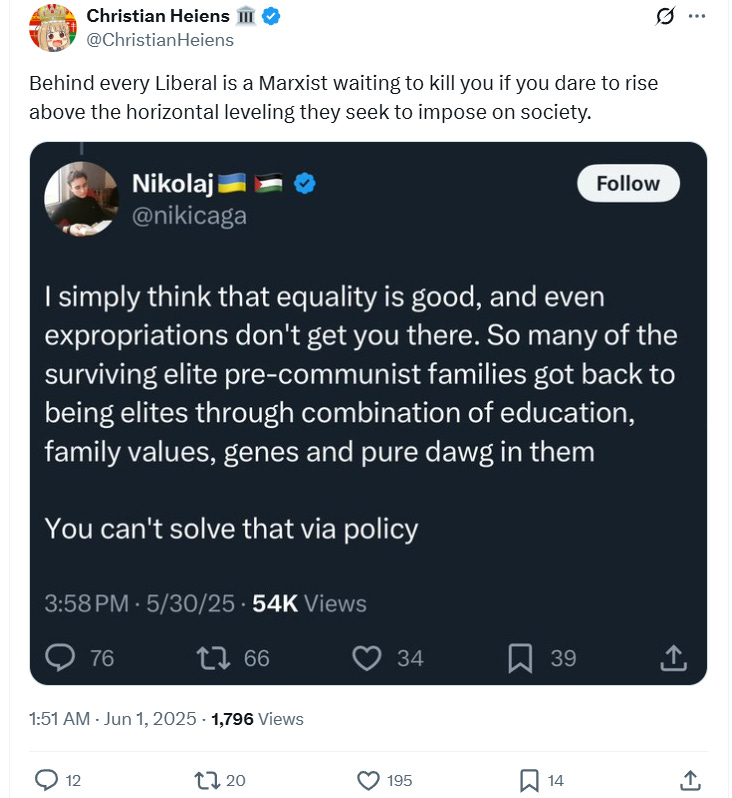

We could say that Marxism, in its early forms, was a resentful, ambitious philosophy generated by the grievances that stem from these insights.

It’s not a coincidence that Marxism emerged into prominence as a philosophy in 1848, a few years after the end of the First Industrial Revolution, at the same time as the pressure valve of colonialism and European expansion had crashed into diminishing returns. The first wave of colonialism had begun to fail. Latin American colonies had rebelled, and won their independence during the previous decades. The economic model of plantation-slavery no longer made sense. And in a striking irony, France abolished slavery in 1848… the same year that Marx and Engels published Das Kapital in London… and the same year that revolutions swept across Europe.

It’s worth speculating about the role Britain played in the Revolutions of 1848…

But when there was an open frontier, the internal contradictions and seething discontent of society could be funneled elsewhere — angry young men with fiery eyes and hungry ambitions could be sent to make trouble in foreign lands. When the frontier closed, ever so briefly between the first era of colonialism and the second, the proximate result was massive unrest in Europe, and the overthrow or coerced reform of many of the European monarchies.

America today experiences similar unrest… a closed frontier, and an excess of aimless, angry young men who feel shut out of the civilizational machine…

Many unexpected social phenomena begin to make sense after you internalize the core idea of industrial society as a vast machine of distributed networked resources that results in implicit technological dependence, which conditions a sense of subconscious passivity. Problems feel too big for anyone to solve. Trends can continue for a long time if no one stops them. Every problem that scales becomes a persistent, systemic crisis that requires coordinated teamwork to solve. Moral panics, preference cascades, fashion trends… outbursts of peculiar group behavior ripple through the machine’s conduits in abrupt, violent paroxysms.

The Dissident Writer, The Return of Elites:

“One of the truths about capitalism and market economics is that it does not select for virtue or even talent in the conventional sense. It selects for the ability and willingness to find gaps in the rules and the ability to ruthlessly exploit them. The tech barons found a gap in property laws, for example, that allows them to steal your information and then sell it to government and business. Without this loophole, the giant social media platforms collapse overnight.

The result of this system that randomly awards people with opportunity and then lavishly regards those who are willing to ruthlessly exploit the opportunity is an oligarchy composed of sociopathic lottery winners. The weird social politics that defines the attitudes of our elite are both a defense against similar lottery winners lurking below and a justification for their position. They are not just lottery winners, but members of an elect, fated to hold positions in the elite.”

—The Dissident Writer, The Return of Elites

Civilization is an engine.

A rattling, oil-slick beast stitched together from centuries of friction and compromise, humming beneath the skin of cities like a second circulatory system.

Like any machine, society requires structure: levels, modules, functions. Components at the top operate the dashboard; components at the bottom carry the weight, grind the gears, absorb the heat.

It’s not personal. That’s the most personal part.

Pain is never evenly distributed — it flows downhill.

The system survives by offloading entropy, risk, and damage to those least capable of resisting.

Tasks are assigned via signal capture. The machine channels surplus up the pyramid and externalizes decay downward. Modules don't erase threats, they just displace them. The bottom absorbs the shock while the top rides in self-driving comfort.

Hierarchy is thermoeconomic: those closest to the algorithmic core are buffered from volatility, while the periphery absorbs systemic risk like a sponge. The bottom is not a class but a process — risk digestion, collapse amortization, surplus absorption. Bottom dwellers are the sacrificial strata.

The Morlocks scuttle in filthy, subterranean sewers, and the winged Eloi soar above them, gliding in relative contentment.

To keep the gears turning without revolt, you need myths. Political formulas wrapped in slogans and anthems: freedom, democracy, progress, meritocracy, patriotism. Rationalizations and justifications; ideological white noise to dampen panic, to smooth over the horror of being reduced to a function. Myth is not optional; it is lubrication for the machine’s internal contradictions.

Society is fragile. It needs stories that feel true even when they’re not — especially then. Each citizen must believe they’re part of a grand machine of justice, even as the oil from its workings stains their hands. Participants chant their roles like mantras. The machine feeds on belief, repackaged and resold daily, upgraded with each election cycle, retrofitted with each corporate rebrand.

In the end, civilization is a distributed hallucination — a shared delusion with real consequences. And like any good system, it makes sure those consequences fall on someone else.

The “conservative” answer is to be personally content and collectively apathetic, to remain indifferent by ignoring the structural asymmetries embedded into the organization of industrial society.

The Marxist solution attempts to grapple more honestly with the ugly externalities and procedures of civilization, but fails as a result of seething malice and resentment. The film Snowpiercer (2013) is a beautiful metaphor for how the old school of economic Marxists (rather than the new school of dysgenic Bioleninists) view industrial society: a vast cage which must be rebelled against, and then torn down and immolated, in an attempt to escape from the unfairness and injustice of any form of social hierarchy. For Marxists, the human condition itself is the enemy, and to follow their cold logic to its inevitable conclusions results in an Aztec death cult determined to build a new Babylon, a new Sodom and Gomorrah, in the hopes that their sins will drown the Earth in the blood of the innocent — until God himself returns to destroy the world. And if God refuses to deliver apocalypse, Marxists attempt to execute the End-of-the-World crusade by themselves.

All of this is a little extreme. It’s the bloodthirsty excess of a religious delusion.

Leadership can solve this — someone needs to make the TRAINS RUN ON TIME.

The miracle of civilization is that anyone can escape from the brutal competition of the natural world, finding peace, security, and comfort in technological society. Hierarchy is inescapable. But a good civilization must live up to its own book of rules. Promises must be honored. Slogans must be converted to reality on a dependable, regular basis.

In human society, a rising tide doesn’t lift all boats, and especially, a rising tide doesn’t lift all boats at the same rate. Benefits are never evenly distributed across a continent. Rewards and punishments remain localized.

There will always be suffering, injustice, and unfairness.

Equality is a fiction.

But the machine of civilization must protect and provide for most of its constituents, most of the time. People who feel trapped at the bottom need a pathway available to climb higher, based on a clear ethical code of behavior. Exemplary achievements must be recognized, applauded, and rewarded on a consistent basis. Pareto’s circulation of elites creates a sense of fairness, and an ongoing process of elevating great men. Witnessing battle-tested heroes receive generous rewards has the effect of inspiring young dreamers to believe that someday their own turn can arrive to ascend to Mount Olympus, rescuing damsels and slaying gorgons with deeds of outstanding heroism. Elites at the top who violate and betray their responsibilities need to be punished accordingly, rather than insulated and forgiven because of personal connections. Fraud must be audited, and swiftly corrected. If people want to improve their own lives, they need to be given a prosocial ladder to success which is easier than organizing into a critical mass of alienated young men to tear down the nation’s scaffolding.

Anything less, and the machine breaks.

This is a serious piece dealing with the exact things that most people are often overlooking.

And yes, we're all a part of this machine, but as more people realize that fact -- more people just might start to change the way they look at things.

At least that's a start.

This is why we need Mars colonization + opening up federal land, etc.

If people have an open frontier to escape to and experiment on, then tinkering with the "machine" or exiting it and founding your own is legal, taking away many of the bad social incentives of a closed system.

I have hopes that certain new technologies, like Dr. Harold White's Casimir energy technology, could give us such a future, whether or not the governments want us to have it: https://grainofwheat.substack.com/p/the-quantum-powered-nomads-of-the?r=1mcpmt