“It's better to conquer grief than to deceive it.”

—Seneca

“Brief is man’s life and small the nook of the Earth where he lives; brief, too, is the longest posthumous fame, buoyed only by a succession of poor human beings who will very soon die and who know little of themselves, much less of someone who died long ago.”

—Marcus Aurelius

George R. R. Martin has forced his fans to wait fourteen years (so far) for the long-promised, long-delayed, never-delivered manuscript of The Winds of Winter. His most recent installment of the franchise, A Dance with Dragons, was published in July 2011.

This hiatus has stretched on longer than the Napoleonic Wars (1803 to 1815).

It’s frustrating, it’s funny, it’s unprofessional — but mostly I think this is sad, for someone to spend forty years developing their creative talents, to painstakingly climb to the top of a ferociously competitive ecosystem of entertainment, and then for someone to waste that rare talent, to abandon their globally-acclaimed dreams, to neglect their magnum opus…

And why?

For what reason?

Fear… laziness… doubt… disorganization… distraction… take your pick. Some combination of these impulses.

It’s a shame.

Talent is rare, most artists never find an audience, most sequels fail to match the original debut’s quality, so it’s disappointing for George R. R. Martin to write five mammoth bestsellers and then spend his time on everything except his life’s work.

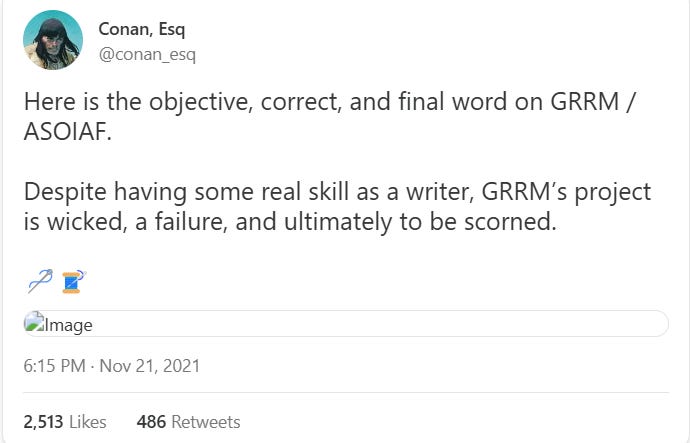

My friend Conan_esq argues persuasively that George R. R. Martin’s magnum opus was doomed to failure, and lacked a satisfying ending from the start, because the author’s nihilistic morality clashed against the heroic genre conventions of epic fantasy.

Conan Esquire said,

“The real central core of the argument is that Game of Thrones ultimately fails, the project ultimately fails, George R. R. Martin can’t finish the series, because he decided to write an epic fantasy series with a theme that is directly opposed to the structure of an epic fantasy series. What I mean by that is he writes this series to be a sort of quasi-nihilistic inversion of the heroic moral themes that come out of the structure of a traditional epic fantasy story. Epic fantasies are designed to produce certain types of themes, and by themes I mean implicit moral arguments that the book is making.

…

A good work of art, a good novel, painting, or film does carry some thematic moral point. And the moral point that George R. R. Martin is trying to make with the Song of Ice and Fire project is diametrically opposed to the very structure of the work that he’s creating.”

—Conan_esq

Game of Thrones vs Lord of the Rings

Conan_esq presents a grandiose, eloquent explanation.

I think the truth is a little sadder, and more pathetic than that.

Glen Cook’s The Black Company was one of the inspirations for Game of Thrones, providing a prototype for the black-clad criminals of The Night’s Watch, and Glen Cook already demonstrated an elegant solution to this problem — how to write an epic fantasy series with nihilistic morality that ends on a satisfying note.

The reality is that George R. R. Martin is lazy and unproductive, because he’s obese and lacks mental toughness, but also because his daily routine is poorly-designed, which causes his lifestyle to atrophy into terrible inefficiency.

Martin’s failure to complete his critically-acclaimed, commercially-profitable, culturally-impactful magnum opus is a cautionary tale to any aspiring artist. It doesn’t matter how creative you are, or how talented. You need to design your life to empower aesthetic productivity, and to implement habits that encourage the best version of yourself to perform at an elite level.

If you are relying on sheer willpower for a prolonged period of time, that’s a self-defeating strategy.

George R. R. Martin quit working because the project had stretched on for roughly twenty years, and the actual writing had become hard, boring, painful, tedious labor with no end in sight. He began writing Game of Thrones in 1991, when his Hollywood screenwriting career was profitable but obscure, unsatisfying, and lacked accolades. At that point, George R. R. Martin had a desperate, burning desire to accomplish something significant, and to achieve renown with his stories. By the time A Dance with Dragons was published in 2011, he was a different person, with a different set of ambitions, and any sense of urgency had dissipated. Twenty years had elapsed, George R. R. Martin was rich and famous, his books had been embedded into the cultural pantheon, and there was no longer this insecure drive to prove himself. It was easy to slack off, to stop writing, to travel around the world to conventions and media events, enjoying food and fans and historical reenactments.

Martin was invited to conventions, television interviews, guest appearances on talk shows. His life became a whirlwind of promotional events and side projects. The man became a brand. And brands don’t write books; they sell them.

Each manuscript in the Song of Ice and Fire saga was a ponderous, daunting, Herculean task which George R. R. Martin often referred to as “King Kong, the monkey on my back”.

This negative, pessimistic attitude of complaining about his victories reveals that George R. R. Martin had lost the childish joy of creation which originally conceived Game of Thrones.

Bad habits, and a poor work process, will beat your enthusiasm out of you, even during success.

It’s crazy that the manuscript for The Winds of Winter has been delayed for fourteen years, and remains unfulfilled, unfinished, unscheduled. If George R. R. Martin had written one page per day, or even half a page per day, while allowing himself to keep writing on days when the work was humming along smoothly, then the entire series would be finished by now. These long delays and distractions and detours are paralyzing, because they siphon momentum.

George R. R. Martin is capable of writing much faster than this, while retaining a consistent baseline of exceptional quality.

It’s a choice to write slowly, to avoid making progress on his flagship series, to be consumed by anxiety and guilt and distractions and disorganization — but it’s an unconscious choice, which he has accidentally regressed into.

During the writing of A Storm of Swords, George R. R. Martin was able to produce five polished pages of manuscript per day — for an entire month. He was locked in. But this was a special time in his life. He knew what he wanted to write, most of the novels’ chapters had already been planned out on some level, and his life was designed to eliminate distractions and tertiary obligations — he wasn’t spending half the year traveling to fan conventions, or supervising merchandise. The first two novels were successful, and he knew there was an established audience with real enthusiasm for the franchise, but at that point the audience was not fanatically loyal to the story, and a genuine deadline existed to ship the next manuscript before a large segment of readers got bored and permanently wandered off.

Success allowed George R. R. Martin to slack off and enjoy life. So he did, and for years it was the most fun he’d ever experienced, savoring the moderate celebrity of his status as a bestselling fantasy author.

Writing, Reading, Writing | Not a Blog

Disorganization is killing this series.

Martin’s worst mistake is that he doesn’t write when traveling, because he doesn’t want to bring his computer with him. Fear grows the more you avoid it. So traveling starts out as an innocuous distraction, a necessary business activity of self-promotion and professional networking, but his creative momentum is obstructed by these frequent detours, and the longer he spends away from the keyboard, the more his doubts and disorganization grows into a serious case of performance anxiety, where George R. R. Martin no longer believes he is capable of writing anything worth reading.

It’s sad.

More than that, it’s completely unnecessary. A self-inflicted, unforced error.

The most interesting aspect of this long-stalled installment is the technical narrative structure of the Song of Ice and Fire series.

Most stories are written with a beginning, middle, and end. There’s a clear structure, and a clear resolution.

George R. R. Martin describes that kind of conventional structure as architecture, and refers to himself more as a gardener.

It took me many years to figure out what this “gardening” metaphor actually means, rather than some vague poetic buzzword that sounds impressive without signifying anything of real substance. I am skeptical whether George R. R. Martin himself has figured out his own creative process in mechanical terms, since he keeps being surprised by his own story’s expansion. Originally, Game of Thrones was sold to publishers as a trilogy. Then it grew… and grew… and grew to a total of seven scheduled books. It’s possible the series would keep growing to a total of eight or nine books, if written according to the franchise’s current vision, ambition, and pacing.

What makes Game of Thrones special, compared against every other book in the bookstore, is the texture, depth, and multifaceted complexity of the world of Essos and Westeros — every offhand remark, every casual description, every background character has the potential to step out from the background and take a leading role in the brutal wars, treacherous political intrigues, and occult mysteries of the story.

A good example is this passage from one of the earliest chapters of Game of Thrones, selected from Ned Stark’s first viewpoint chapter, when Robert Baratheon rides to Winterfell to invite Ned Stark to replace their murdered rolemodel Jon Arryn as the new King’s Hand. Most of these locations were mentioned offhand by George R. R. Martin, without any forethought or prepared design. But all of these locations were major set pieces by the second novel in the series, and were later fleshed out for hundreds of pages:

George R. R. Martin, A Game of Thrones:

““The winters are hard,” Ned admitted. “But the Starks will endure. We always have.”

“You need to come south,” Robert told him. “You need a taste of summer before it flees. In Highgarden, there are fields of golden roses that stretch away as far as the eye can see. The fruits are so ripe they explode in your mouth — melons, peaches, fireplums, you’ve never tasted such sweetness. You’ll see, I brought you some. Even at Storm’s End, with that good wind off the bay, the days are so hot you can barely move. And you ought to see the towns, Ned! Flowers everywhere, the markets bursting with food, the summerwines so cheap and so good that you can get drunk just breathing the air. Everyone is fat and drunk and rich.” He laughed and slapped his own ample stomach a thump. “And the girls, Ned!” he exclaimed, his eyes sparkling. “I swear, women lose all modesty in the heat. They swim naked in the river, right beneath the castle. Even in the streets, it’s too damn hot for wool or fur, so they go around in these short gowns, silk if they have the silver and cotton if not, but it’s all the same when they start sweating and the cloth sticks to their skin, they might as well be naked.”

The king laughed happily.

Robert Baratheon had always been a man of huge appetites, a man who knew how to take his pleasures. That was not a charge anyone could lay at the door of Eddard Stark. Yet Ned could not help but notice that those pleasures were taking a toll on the king. Robert was breathing heavily by the time they reached the bottom of the stairs, his face red in the lantern light as they stepped out into the darkness of the crypt.”

—George R. R. Martin, A Game of Thrones

Highgarden and Storm’s End didn’t exist before this dialogue, and were invented merely to provide background color. Later they were the source of fascinating characters, and the site of pivotal battles.

Without this conversation, it’s possible that Renly Baratheon; Stannis Baratheon; Olenna Tyrell (The Queen of Thorns); Margaery Tyrell; Loras Tyrell never would’ve existed, or any of their supporting characters and related subplots — Ser Davos Seaworth, Melisandre and The Lord of Light, Brienne of Tarth, The Battle of the Blackwater, The Purple Wedding, The High Sparrow and the newly-awakened Faith, Cersei’s Walk of Shame — it’s impossible to know. But none of these events were part of the original plan, although in retrospect it’s difficult to visualize Game of Thrones without these events, characters, and ideas. George R. R. Martin allowed his series to grow like an untamed weed, branching out in dizzying spirals, as he refused to prune or tame the story’s natural impulses.

The beauty of this series has always been its lack of discipline — specifically, the undisciplined and unconstrained wild growth and expansion of subplots, supporting characters, locations, symbols, and themes.

The “gardener” process Martin champions — a narrative model based on organic evolution rather than fixed design — is, in essence, a hyperstitional machine, one that breeds self-amplifying tangents. Every added character, each branching subplot expands the franchise’s dimensionality… rather than steering the epic saga towards a satisfying conclusion. The story’s structures mirror complex systems theory: each new layer doesn’t clarify, but rather amplifies the interconnected web of plots and players. Rather than progressing in a linear fashion, each storyline develops connections that lead to ornamental, unpredictable narrative roots. The series is built upon beautiful, unnecessary spandrels.

Every decision births a cascade of subplots and character developments, interlacing like the fibers of an intricate web.

The story started simple enough — a sprawling tale of power, vengeance, and ice-bound kingdoms. What was meant to be a relatively straightforward epic became a sprawling labyrinth, broadening and deepening with every turn.

How does this process work?

It’s mathematical.

Everything in the story is treated seriously; the series rests upon an elegant aesthetic hybrid of grim historical fiction and sprawling epic fantasy. But whenever interesting dramatic questions and characters are introduced… George R. R. Martin follows the trails of breadcrumbs, no matter where they might lead.

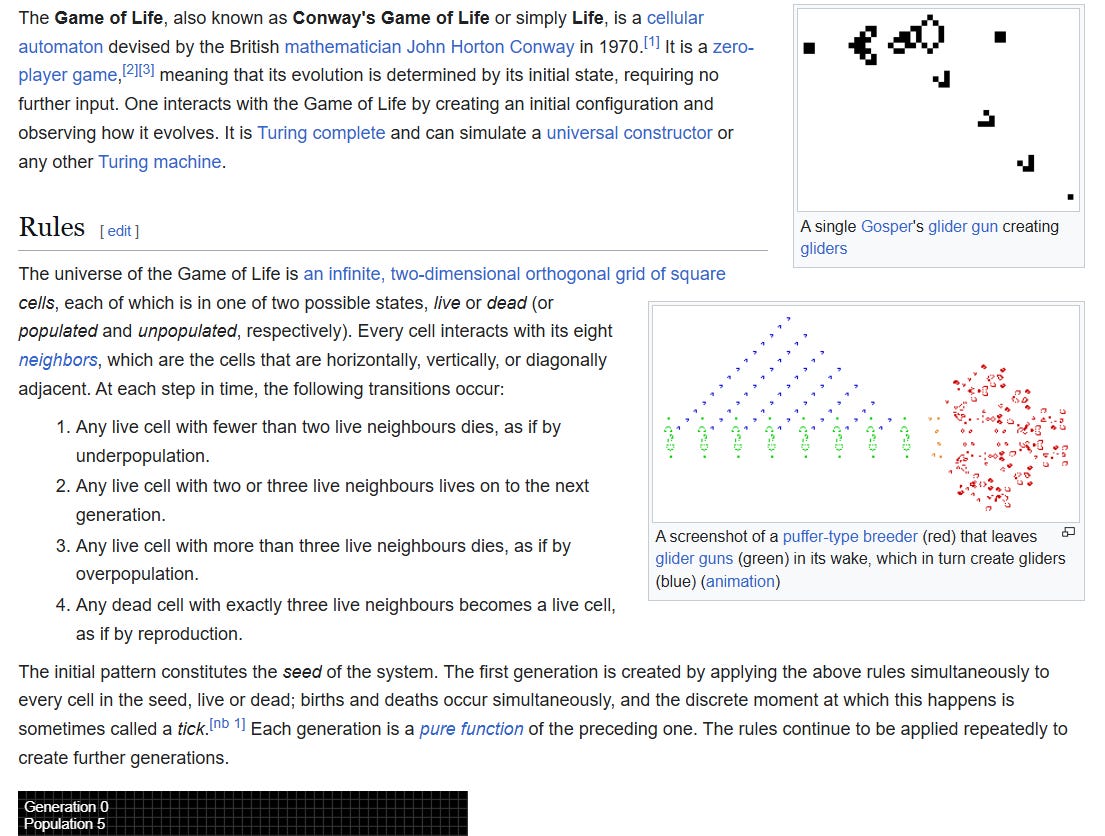

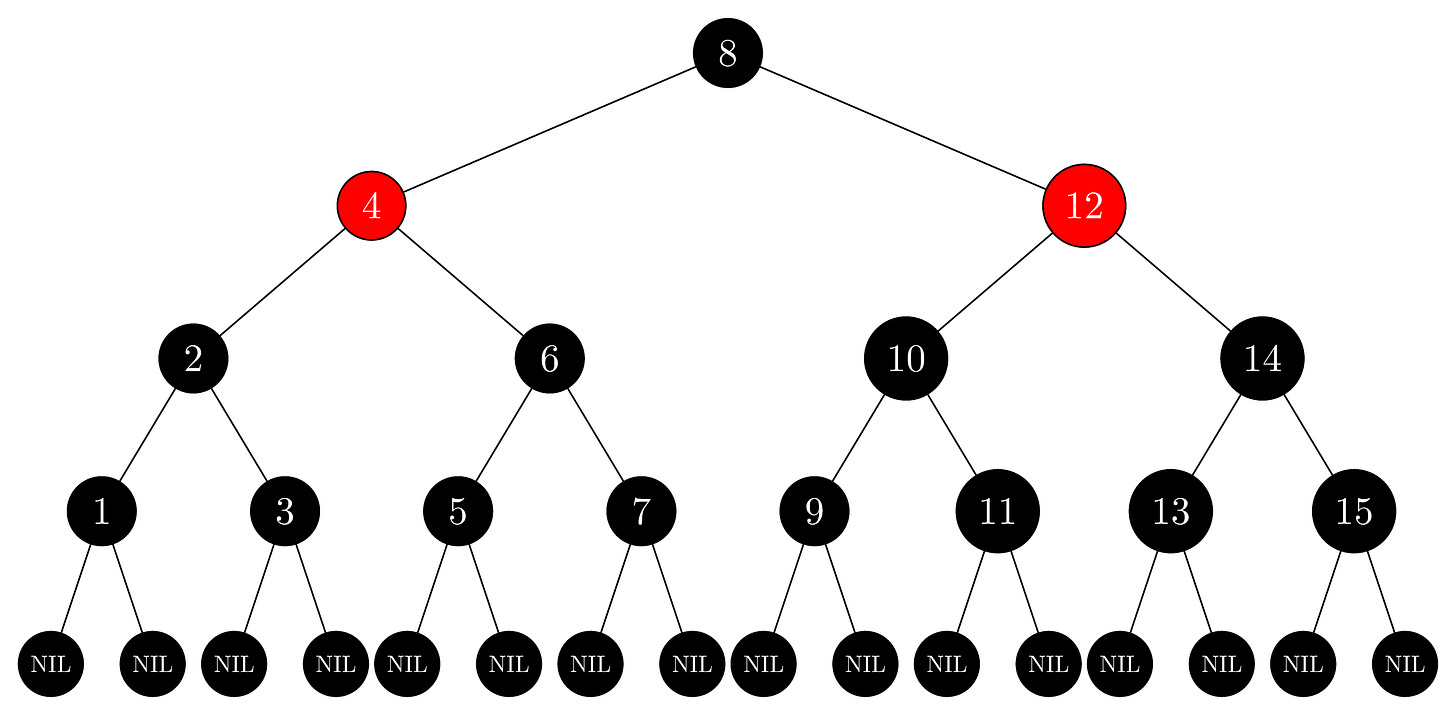

In other words, this franchise is designed similar to the famous mathematical logic of cellular automata, as pioneered by John Conway’s Game of Life in 1970.

It’s a game, and the game is simple.

The gameboard starts out with an initial condition, and a set of consistent aesthetic rules which govern the behavior of all existing narrative components. The game is seeded, and then plays out in looping rounds. Based upon the honest documenting of simple patterns, this very basic logic results in astonishing complexity which seems to exponentially spring out of nowhere. But when readers trace back individual, unpredictable choices, betrayals, and plot twists, a consistent logic is revealed to be guiding the self-replicating patterns of this emergent system.

George R. R. Martin seeds his world with interesting characters, and he allows them to pursue their own ambitions according to their strengths.

George R. R. Martin seeds his world with philosophically-oriented factions, and he allows them to betray each other, according to political expediency.

George R. R. Martin seeds his world with macroeconomic trends, and he allows each family to respond to famines, wars, assassinations, migrations, economic upheavals, religious disputes to advance their own (perceived) self-interest.

George R. R. Martin designs his heroes with tragic flaws, and then allows iconic heroes to destroy themselves. Important characters suffer deaths which are abrupt and symbolic.

Then he documents the results honestly.

It sounds very simplistic, and in a sense, it is.

But it’s a massive amount of work to allow a plot to keep branching and branching, without pruning or shaping the tangled, diverging chaos that rapidly emerges from a seed of initial conditions. There are severe problems of pacing and character viewpoint which emerge from this strategy of concurrent complexity.

ZeroHPLovecraft’s The Gig Economy provides the most poetic description of cellular automata which I’ve come across:

“From his height, eight miles above the ground, his voice was amplified by the geometry of the tower.

Every worker in the tower and every resident in the city below could hear the song; it’s subtle melody eluded articulation. It seemed to slink around the corner of the mind; it was the sound of half-heard laughter far away, maybe even imagined. To every every listener it had different lyrics, which came at first spontaneously, and which evolved according to an inevitable self-contained logic.

The song was a game which revealed its own rules own rules to the singer in the the act of singing. To follow the rules was to sing the song, and to sing the song was to learn the rules, which were ever shifting and ever expanding. The builders of the tower could find no commonality between their songs. Each was lost in his own idiosyncratic rendition of the high priest’s prayer, and no two could understand each other. They dispersed, abandoning their great work. They realized that the purpose of the tower had been to find the song.

In some alien algebra, the tower was isomorphic to the song. Put another way, the tower was the song. In the computational environment of the tower, there persisted algorithms and registters, state machines and subroutines. In the computational environment of the song, all of those entities existed also. The high priest, who wore the stone around his neck like an amulet, sang untill his voice gave out, and then, choking and coughing, he continued to sing, even until he collapsed. The stone, which had grown warm, now cooled and disinteggrated, and the priest died of exposure, the cold, drying wind desiccating his body.

The builders of the tower became singers of the song. The longer they sang, the more intricate the song grew. It became difficult to hold all the rules in memory. A mistake would yield a sour note; as mistakes accumulated the song would become deranged. Once heard, the tune could not be forgotten. The song was infectious. It beckoned the singer forward, ever eager to know the next verse, filling him with an emotion like hunger or lust.

…

In one such memory, that being of beings emanated a protocol for the virtualization of the human mind. It had planted a seed, which defined a set of initial conditions and an algorithm to compute their consequences. In each iteration of the computation, the seed became bigger. The instructions grew more complicated, the data more immense. In order to perform the calculation, the men of a bygone era had built a tower. The tower was the search for an answer, and its apex had been the solution. When Man looked upon it, he was conscripted into a distributed memetic consciousness running on a process that would span across centuries."

—ZeroHPLovecraft

The diligence, technical fidelity, and attention to detail which is necessary to competently execute this branching, multifaceted pattern with a thrilling, personalized narrative that lasts more than 2,000 pages is exhausting to contemplate.

The brilliance, and stupidity, of George R. R. Martin is that he accidentally stumbled into this mathematical branching pattern, by simply allowing the chaos of his imagination to run free.

He’s a “gardener”.

Not an “architect”.

Nobody else writes like this, or designs a book to operate like this, which is a core reason why Game of Thrones is special. This exotic structure is a key source of product differentiation, which forms a competitive moat against other artists.

George R. R. Martin hides his structure from the audience with various forms of misdirection, concealment, opacity. His books lack a Table of Contents at the start, because listing the sequence of chapters according to character viewpoints would reveal which characters survive, or die.

It takes a long time to figure out how this multifaceted story is being organized, and which nodes are actually important to the network, versus which nodes function as decoys; ornaments; scarecrows.

Character viewpoint is especially puzzling, because in some instances a supporting character will be chosen to observe a more dramatic character (such as Catelyn Stark observing Robb Stark, or Davos Seaworth observing Stannis Baratheon). This is done to hide key information from the audience, which would be revealed by communicating the interior thoughts of the leading character.

But it’s a branching structure based on initial seed conditions, which is allowed to play out with numerous diverging forks, intercutting paths, and occasional convergence, governed by consistent aesthetic rules.

The downsides are obvious, as soon as this pattern is pointed out.

Supporting characters are crowding out the core ensemble of viewpoint characters. It’s a mess.

The first Game of Thrones book had an elegant structure — everything started out with the Stark family at Winterfell, with Danerys Targaryen’s exiled viewpoint in Essos functioning as counterpoint to the primary melody. Ned Stark was the central node which the Stark network rotated around, but he was always intended to be a false hub which would be destroyed, causing the Stark family to splinter. The Lannister family branched out of the Starks at Winterfell.

In other words, Game of Thrones started out with a rotating ensemble cast based around two main leads — Ned Stark, around which every other character clustered, and Danerys Targaryen, who introduced the rule of a split narrative.

But in reality, this dualistic structure was a form of misdirection which concealed the franchise’s actual tripartite structure — instead of two key characters (Ned Stark and Dany), there were three key characters (Jon Snow, Tyrion Lannister, and Danerys Targaryen).

Each of the three main characters served as a camera filming one of the main dramatic conflicts: dragons (Dany), White Walkers (Jon), and political wars (Tyrion).

All very clever, which is to say, designed to confuse and misdirect the audience so that readers could stop trying to track what’s happening and just enjoy the ride of an unpredictable story.

Noise obscures signal.

The initial Game of Thrones novel has a neat, orderly structure — there’s a Prologue chapter where the viewpoint character dies at the end. But every other viewpoint character receives a minimum of 5 chapters. Each chapter averages around 4,000 to 5,000 words.

The branching structure of this epic fantasy saga atrophies into pure chaos by the time we reach later books in the series.

Supporting characters are crowding out the core ensemble of viewpoint characters, and concurrent events in multiple locations are slowing the pacing of other characters, while making it difficult to figure out how to identify the most important events happening across two continents that are suffering various conquests, rebellions, famines, and disorder.

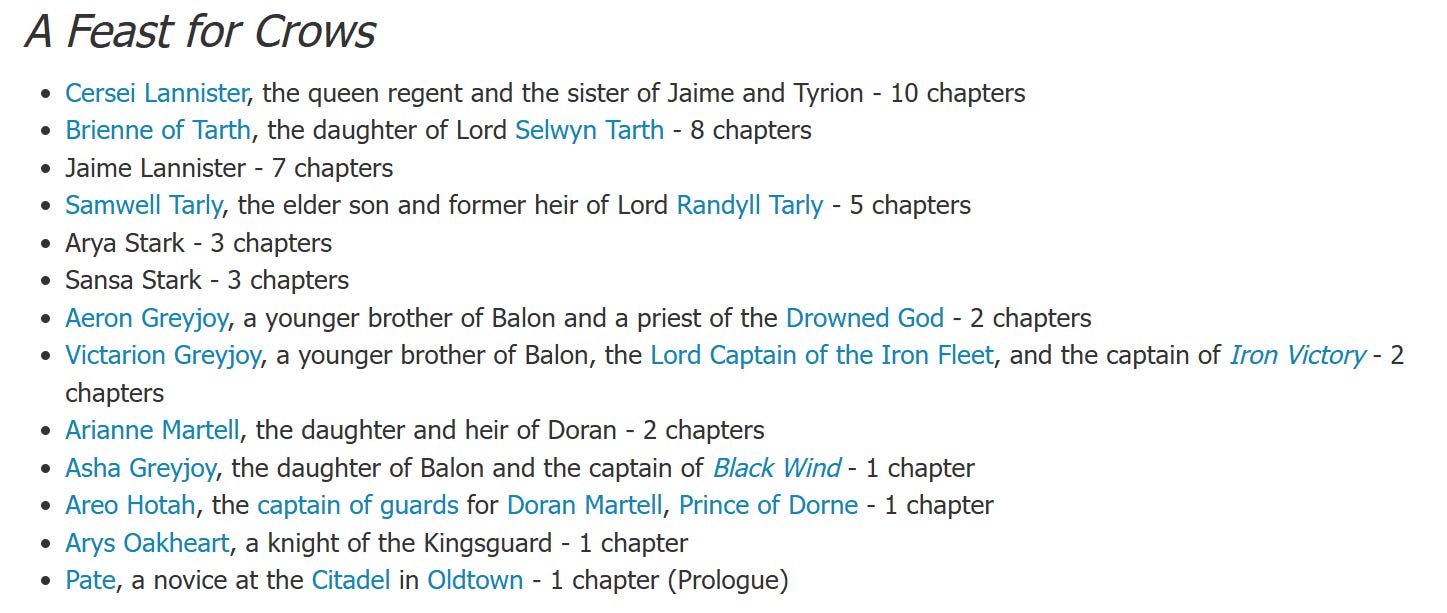

For example, the scattered perspectives of A Feast for Crows are sparse and disorderly:

Aeron Greyjoy, two chapters.

Victarion Greyjoy, two chapters.

Arianne Martell, two chapters.

Asha Greyjoy, one chapter.

Areo Hotah, one chapter.

Arys Oakheart, one chapter.

None of these individual decisions are fatal by themselves, and in fact all of these viewpoints were written beautifully. But the constant intercutting is causing the primary melody of A Song of Ice and Fire to be drowned out in a cacophony of voices, rather than blending together in the harmony of a carefully-choreographed symphony.

When you dig into the statistics, this gets very confusing, very fast, and it’s difficult to see the forest through the trees.

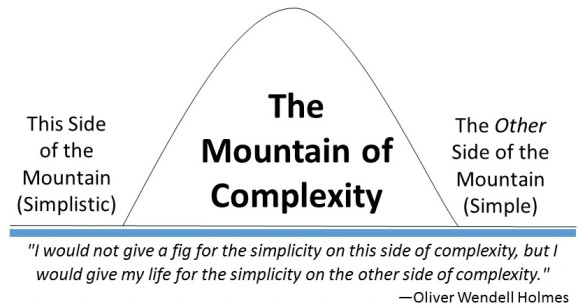

You have to zoom out, far away from this mess, to recover your bearings, and say — the problem is very simple: unbounded branching complexity. At some point, complexity needs to be reduced, and all of these branching subplots need to flow together towards some distant, eventual resolution.

The beauty of art, of all narratives, is to begin with the incongruity of disorder, and then amaze the audience by transmuting this chaos into order. That’s the act of catharsis.

That’s the magic trick.

Put the beautiful, busty blonde lady in a box, saw her in half, listen to the audience gasp in horror. Separate the box. Then put the box back together, and watch as the woman steps out in one piece, miraculously unharmed.

Some methods are more clumsy, or elegant, than others. But there needs to be a resolution, an act of redemption, some angle of cutting the Gordian Knot.

Stephen King faced a similar problem with his novel The Stand — a huge ensemble cast of characters, rotating viewpoints, and chaotic structure. His solution was clumsy but effective: to kill off half the characters in an explosion, and to tell the rest of the story with the surviving cast.

Stephen King, On Writing:

“The book that took me the longest to write was The Stand. This is also the one my longtime readers still seem to like the best (there’s something a little depressing about such a united opinion that you did your best work twenty years ago, but we won’t go into that just now, thanks). I finished the first draft about sixteen months after I started it. The Stand took an especially long time because it nearly died going into the third turn and heading for home.

I’d wanted to write a sprawling, multi-character sort of novel — a fantasy epic, if I could manage it — and to that end I employed a shifting-perspective narrative, adding a major character in each chapter of the long first section. Thus Chapter One concerned itself with Stuart Redman, a blue-collar factory worker from Texas; Chapter Two first concerned itself with Fran Goldsmith, a pregnant college girl from Maine, and then returned to Stu; Chapter Three began with Larry Underwood, a rock-and-roll singer in New York, before going back first to Fran, then to Stu Redman again.

My plan was to link all these characters, the good, the bad, and the ugly, in two places: Boulder and Las Vegas. I thought they’d probably end up going to war against one another. The first half of the book also told the story of a man-made virus which sweeps America and the world, wiping out ninety-nine per cent of the human race and utterly destroying our technology-based culture.

I was writing this story near the end of the so-called Energy Crisis in the 1970s, and I had an absolutely marvelous time envisioning a world that went smash during the course of one horrified, infected summer (really not much more than a month). The view was panoramic, detailed, nationwide, and (to me, at least) breathtaking.

…

I liked my story. I liked my characters. And still there came a point when I couldn’t write any longer because I didn’t know what to write. Like Pilgrim in John Bunyan’s epic, I had come to a place where the straight way was lost. I wasn’t the first writer to discover this awful place, and I’m a long way from being the last; this is the land of writer’s block.

…

If I’d had two or even three hundred pages of single-spaced manuscript instead of more than five hundred, I think I would have abandoned The Stand and gone on to something else — God knows I had done it before. But five hundred pages was too great an investment, both in time and in creative energy; I found it impossible to let go. Also, there was this little voice whispering to me that the book was really good, and if I didn’t finish I would regret it forever. So instead of moving on to another project, I started taking long walks (a habit which would, two decades later, get me in a lot of trouble). I took a book or magazine on these walks but rarely opened it, no matter how bored I felt looking at the same old trees and the same old chattering, ill-natured jays and squirrels. Boredom can be a very good thing for someone in a creative jam. I spent those walks being bored and thinking about my gigantic boondoggle of a manuscript. For weeks I got exactly nowhere in my thinking — it all just seemed too hard, too fucking complex. I had run out too many plotlines, and they were in danger of becoming snarled. I circled the problem again and again, beat my fists on it, knocked my head against it… and then one day when I was thinking of nothing much at all, the answer came to me. It arrived whole and complete — gift-wrapped, you could say — in a single bright flash. I ran home and jotted it down on paper, the only time I’ve done such a thing, because I was terrified of forgetting.

What I saw was that the America in which The Stand took place might have been depopulated by the plague, but the world of my story had become dangerously overcrowded — a veritable Calcutta. The solution to where I was stuck, I saw, could be pretty much the same as the situation that got me going — an explosion instead of a plague, but still one quick, hard slash of the Gordian knot.

…

I was also able to analyze what got me going again and appreciate the irony of it: I saved my book by blowing approximately half its major characters to smithereens (there actually ended up being two explosions, the one in Boulder balanced by a similar act of sabotage in Las Vegas).”

—Stephen King, On Writing

So the remedy is simple: when you’re juggling too many ongoing plotlines, some of them need to be resolved. When you have too many characters, some of them need to be killed, crippled, imprisoned, exiled, or otherwise retired.

Stephen King’s explosions embody a brute force answer to complexity. I would prefer a more elegant strategy of compression and convergence, gradually winding down the branching paths, allowing the story to continue unfolding while slightly accelerating the rate of character retirements.

A satisfying ending is when a character reaches the end of their journey, and discovers an important truth — either the truth which saves them by transforming them, or a painful, hideous truth which tragically arrives too late. These iterations of resolutions would allow the multifaceted complexity of Game of Thrones to wind down to a manageable level, once again subsumed into a similar pattern of self-propagating tessellation.

Game of Thrones has grown from simplicity… to complexity… to perplexity.

Readers and critics joked for years that at some point George R. R. Martin would kill off the majority of his characters to truncate the series — eliminated by wars, betrayals, dragons, White Walkers, the Lord of Light.

“I do need to kill a lot more of my point of view characters, because there have gotten to be an awful lot of them. Which ones will die? Well, you'll just have to keep reading to find out.

…

I am, unfortunately, a slow writer. And have always been a slow writer. But I’m a slow writer given to delusions of optimism that I can be a faster writer under certain circumstances. Sometimes I am, but more often I’m not.”

—George R. R. Martin, July 28th, 2011

I think a gradual, systemic process of reducing complexity would have been more subtle, more satisfying than the abrupt, immediate remedy favored by Stephen King.

A pattern of growth could be inverted, towards a pattern of entropy.

A Song of Ice and Fire, and the catalytic combustion of branching, multifaceted plotlines diverging in random directions, could be suffocated by a Song of Dust and Smoke, the convergence and compression of heat and light strangled by the inevitable laws of thermodynamics.

A very slight alteration of the original mathematical patterns that sparked Game of Thrones's Cambrian Explosion, simply by suppressing the normal rates of propagation and self-replication, could neatly and fluidly steer this franchise towards a satisfying ending.

Anyone can write “The End”.

The difficulty is not to stop writing. The difficulty is to maintain a poetic unity of all parts of the work, and to maintain a graceful symmetry of voice, pacing, and overall aesthetic consistency when transitioning from one phase of the series to a radically different phase.

Furthermore, what complicates the difficulty of hitting the brakes on this train is the sheer number of characters, subplots, and dramatic questions which need to be resolved in a thematically meaningful manner — this is why it would not feel cathartic to watch a random dragon kill a couple hundred named characters in a single battle. One scene cannot resolve twenty character arcs at the same time. Each resolution needs time to breathe, and feel properly explored.

A series of goodbyes is necessary, a series of mysteries properly explained, and for a project like Game of Thrones, that process of saying goodbye could easily stretch out for fifty pages of long-anticipated resolutions.

“The man who moves a mountain begins by carrying away small stones.”

—Confucius

There’s a lot of lessons here: keep nibbling away at a big project, retain steady momentum, rely upon disciplined habits rather than willpower or raw creative talent. Complexity can be your friend, it can be a beautiful competitive moat, but scope has a tendency to grow out of control.

Sometimes it’s wrong to take a break. But sometimes the only solution to chaos is to take a step back, zoom out to the right level of detached, dispassionate observation, and inspect a project from first principles to identify the real source of a crisis, rather than getting lost in the peripheral symptoms of an underlying wound.

Another observation I’ll share is this — you need friends who can be honest with you, who will tell you when you are making a mistake, who will bluntly and explicitly articulate the nature of a problem, and perhaps can outline the suggestions of a solution.

George R. R. Martin surrounds himself with sycophants, and he doesn’t really want to hear criticism. Especially when it’s painful, and requires a radical surgery to amputate the patient.

One thing I was amazed by was the following conversation, where George R. R. Martin asked Stephen King for advice. And rather than surgically dissecting Martin’s obvious mistakes and inefficient habits, presented from the perspective of a friend and a bestselling author who Martin respects, Stephen King (selfishly) chose instead to focus on their existing friendship and to provide false reassurance that comforted George R. R. Martin to remain stagnant and continue on with a failed strategy.

The correct move would’ve been to pull George R. R. Martin aside and privately explain to him that his life was designed for failure, while encouraging Martin that a change was practical, feasible, and productive.

Stephen King: “George we're going to have to wrap this up pretty soon. Is there anything that you've always wanted to ask me? Because George, I will.”

George R. R. Martin: “Yes, yes there is something I want to ask you: How the fuck do you write so many books so fast? I think ‘oh, I've had a really good six months, I've written three chapters’ — and you've finished three books in that time.”

SK: “Here's the thing, okay, there are books, and there are books. The way that I work, I try to get out there and I try to get six pages a day. So with a book like End of Watch, I work, and when I'm working I work every day for about three or four hours. I try to get those six pages. And I try to get them fairly clean. So if the manuscript is — let's say three hundred and sixty pages long — that's basically two months work. It's concentrated, but it's a fairly extensive amount. That's assuming that it goes well.”

GR: “And you do hit six pages a day?

SK: “I usually do.”

GR: “You don't ever have a day where you sit down there and it's like constipation and you write a sentence… and you hate the sentence… and you check your email… and you wonder if you had any talent after all — and maybe you should have been a plumber? Don’t you have days like that?”

SK: “No, I mean there’s always real life happening, outside of artistic creation. You know, I can be working away and something comes up. And you have to basically get up… and you have to go to see the doctor, or you have to take somebody a care package. Or you have to go to the post office, because whatever. But mostly I try to get the six pages in. Although entropy tries to intervene!”

…

SK: “You know, I did an event at Radio City Music Hall for charity with John Irving and J. K. Rowling. This was at the time that she was finishing the seventh Harry Potter book. And I know that I've been very fortunate as a writer. You've also been terrifically fortunate as a writer, George. You worked for a long time; wrote a lot of good books; won a lot of awards, and then out of nowhere all of a sudden this crazy thing happens where all these books are suddenly New York Times bestsellers — and God knows it’s deserved — but it's a sort of sudden thing. Here's the other thing, okay: People yell at you. Audiences say ‘We want the next book! We want the next book!’ They're like babies: ‘We want the next book, right away!’ I mean, it's a great problem that audiences want to purchase your stories, but the pressure that you feel or I feel is small compared to that final Harry Potter book. You know, everybody wanted that final Harry Potter novel. And she came to New York, and she was nearly finished with it, and she'd agreed to do this event. Joe was trying to do three things at once: she was going to do a vacation with her kids, she was going to finish the last five or six chapters of the seventh Harry Potter book, and she was going to speak at this charity event. She showed up to do the soundcheck at Radio City Music Hall. And she was dressed like any housewife or mother or anyone who was on vacation. She had a shell top on, white clam digger pants, and loafers or sandals or something, and her hair tied back in horse tails. We were trying to talk about what we were going to do. Then the Scholastic Press publisher is pulling her aside, and talking to her. And Joe is very polite. But when she came back and talked to me, she was really really angry. And what she said was ‘They don't understand what we do, do they?’ And I said, ‘How can they understand, when we don't understand?’”

GR: “All too true.”

There was a note of sadness in George R. R. Martin’s voice when he said, “All too true”. A subtle hint of despair. He came to Stephen King looking for help. But he didn’t get it.

Talent is a gift from God. But discipline, organization, persistence, and efficient habits are a choice — an unconscious choice, evaded or committed to on a daily basis. Our lives are shaped by the tiny, incremental accumulation of habits so small that they seem to be insignificant.

When the book published in 2011 introduces additional characters with claims to the throne, it dawned on me that he didn’t actually know where he was going.

While the writing was still good, he had clearly wandered into the same morass of being unable to drive the plot towards resolution, much like how books 8-11 (over 2400 pages!) of the Wheel of Time featured a grand total of one major plot milestone and a whole lot of events that I barely remembered and that were largely irrelevant to the final events in the last two books of the series that had to be finished by Brandon Sanderson because, love him or hate him, Sanderson knows how to advance a plot in a mostly coherent fashion.

2 huge problems are how young many main characters are and that all the published books cover only a year of the half. GoT viewers might miss the point that at the beginning of the ASOIAF Dany and Jon are 14 and Arya is 9 and they barely get any older in the books.

GRRM was planning a 5 year time skip in the original trilogy but he failed to achieve it so now he is stuck with an 10 years old girl who is supposed to kill the NIght King.

As someone who has read most of the stuff GRRM wrote I think he is seriously overrated.