Not a movie I recommend watching.

But a fascinating case study because it features the intersection of three trends: cinematic storytelling, contemporary ideological-political conflict in America, and a masterful sales campaign which brilliantly deceived audiences (with the help of professional critics, and a studio ecosystem dependent on blockbuster profits).

Spoilers below.

Alex’s Garland’s Civil War is one of the most misrepresented films I can remember in many years. I’m reminded of the recent disappointment of The Matrix 4, otherwise known as “The Matrix Resurrections”, which failed to resurrect Neo and The Matrix, and instead featured awkward scenes of Neo sitting in therapy as a depressed and directionless adult.

The marketing campaign for this film has been marvelous.

The people who promoted this movie deserve every dollar they’re paid, and it’s amazing they managed to sell this product as a global, cinematic “Blockbuster Event”.

Because the film itself is a dud. It’s a boring movie in a fascinating setting, which is a near-future America torn apart by internal warfare.

You are not watching a blockbuster action movie.

In fact, this movie is designed as a theatrical stage production which incidentally features a detailed background colored by the motion and visual effects of a film, with none of the scale, adventure, or excitement expected from a big-budget production. The conversations are slow, small, quiet, and intimate.

This is a stage production in the tradition of “Waiting for Godot”, where the movie is designed around an event that never happens… and instead, the audience sits around observing incidental dialogues that provide psychological character studies. The film is shot in a sort of cinéma vérité aesthetic, also known as truthful cinema, or observational cinema, where a sort of fake authenticity plays out in order to communicate the pseudo-integrity veneer of honest exploration of the human condition.

That’s the kind of paradox which might fascinate Jean Baudrillard, and indeed the need for fake authenticity says some interesting things about the desperation of the current American Regime’s need to hide behind brittle illusions as quality of life declines for the majority of citizens — but the provocative truths which this movie avoids are more intriguing than anything that happens onscreen.

We live in a postmodern Regime, where basic truths have been abandoned in order to socially construct a curated simulacrum of reality, which increasingly fails to inspire, persuade, sedate, or suppress its critics.

This movie should be analyzed… dissected… vivisected… dismembered with the postmodern toolkit.

The film bends truth into peculiar forms, and these distortions provide us with insightful reflections into how the Woke American Regime perceives itself. How the ruling coalition perceives institutional vulnerabilities… domestic discontent… and what justifications are formulated as post-hoc legitimating myths to explain why authority is concentrated in current factions.

Perhaps better than anyone, ZeroHPLovecraft explains some of the mechanisms of postmodern analysis:

ZeroHPLovecraft, “Zero HP Lovecraft and the Fallen State of Literature”:

“In my opinion there is no death of the author, it’s a specious concept, pure sophistry. It’s true that a work may mean different things to different people, but mostly it’s a pretense to justify leftist and revolutionary readings of authors who would be deeply insulted to find their works interpreted in these ways. I think the written works of an author are inextricable from who that author is, because his written works are an attempt to transliterate the contents of his mind.

The death of the author begins with a true premise, which is that the meaning of a work may not be what the author consciously intended – so often we are unaware of our own motivations, although a good author should be more aware – so it may be that the author is wrong about what his work means. The viewpoints of a character within a work are not necessarily the viewpoints of an author, but the author’s sincere beliefs about the world are always present in the text, in one form or another. If they are not explicitly stated, then they are implicit. In my opinion, Barthes’ formulation elides this distinction.

A similar failure mode is present in Derrida’s notion of the trace, which he uses to produce his deconstructions. Derrida says that whatever is not mentioned in the work is present by virtue of its absence. This is tautological, and it allows him to add anything to any work he wants, and then claim, “because the text doesn’t say this, the shadow of what it doesn’t say hangs over it, and because of this latent contradiction, it deconstructs itself.”

In both cases, you have a truth:

Barthes - an author may communicate something he does not intend

Derrida - there may be a conspicuous absence

Which is then exaggerated into a falsehood:

Barthes - the intentions of the author are irrelevant

Derrida - the absence of a concept is evidence of its centrality

You can use the “Derridean device” to interpret any text to mean anything at all. Postmodernists view this as a feature of all texts, but they should view it as an indicator of a fatal flaw in Derrida’s thinking. Always beware of the theorem that explains too much. To circle back to Bloom, perhaps writers employ these “techniques” as a way to overcome the anxiety of their influences. It’s certainly tempting to say that they are resentful ways of reading.”

—ZeroHPLovecraft, “Zero HP Lovecraft and the Fallen State of Literature”

Interviewed by @FlightAstral - Zero HP Lovecraft (substack.com)

Zero HP Lovecraft and the Fallen State of Literature – Astral Projections (wordpress.com)

What does postmodernism tell us about Alex Garland’s Civil War?

There is indeed a conspicuous absence, as Jacques Derrida might propose…

More than one.

Why are the American factions fighting? How long has the war been raging? Who is leading the rebels? Why did domestic political tensions escalate from hostile rhetoric to actual violence?

What event started the Civil War? Who are the villains? Who are the heroes? Could war have been avoided? Did the war begin as a mistake, a crime, a tragedy? Or was the war an inevitable result of incompatible ideological tensions?

None of this is answered.

Any semblance of morality is explicitly avoided, and suppressed in this film — a profound act of nihilism. Neither the ascendant rebels, nor the besieged incumbents, can offer even the pretense of a moral claim to vindicate their struggle.

Almost an hour into the film, a team of journalists stumble across a slow, intermittent gunfight between snipers. Amazingly, and indeed quite conspicuously, nobody can explain why the war is being fought, or even who the soldiers are:

Journalist: “Hey. What’s going on?”

Sniper: “Someone in that house. They’re stuck. We’re stuck.”

Journalist: “Who do you think they are?”

Spotter: “No idea. “

Journalist: [holds up press badge] “We’re press.”

Spotter: “Cool. Now I understand why it’s written on the side of your vehicle.”

Journalist: “Are you WF? (Western Forces) Who’s giving you orders?”

Spotter: “No one’s giving us orders, man. Someone’s trying to kill us. We’re trying to kill them.”

Journalist: “You don’t know what side you’re fighting for?”

Spotter: “Oh, I get it. You’re retarded. You don’t understand a word I say.” (He turns towards a rookie female journalist on her first assignment) “Yo. What’s over there in that house?”

Female rookie journalist: “Someone shooting.”

(The spotter smiles, vindicated, as if asking the enemy’s identity was a dumb question).

This is terrible writing because it takes a long time, says nothing, and reduces clarity. The dialogue destroys value in terms of delivering an immersive, captivating, resonant narrative. The conversation purposefully obscures the film’s primary dramatic question, which is: “So what? Why does any of this matter?”

On a symbolic level, this battle between snipers is presented as a microcosm of the overall war — both sides are stuck in conflict, right and wrong has become elusive or irrelevant, and the battlefield has degenerated to a state where individual soldiers in the field are no longer in contact with their chain of command, and are not bothering to reestablish contact.

Remember the phrase “fake authenticity”.

It’s unrealistic that if squads of soldiers were somehow cut off from their commanding officers, that they would be relaxed and apathetic about operating as rogue elements. This detail was inserted to excuse any military characters of potential moral culpability for the sake of the narrative.

Nihilism pretends to be realistic with a cynical portrayal of humanity. Supposedly war is terrible, so terrible that no one can identify virtue among the carnage.

But in real life, one of the basic truths of good literature and cinema is that everyone sincerely and totally believes they are righteous; every character believes that he or she is the heroic main character of the narrative. Even the monsters. Even the supporting ensemble. Even the cameo roles, who merely walk in the background out of focus — even cameos believe they are the movie’s main character.

In war, especially a brutal internecine conflict, both sides loudly proclaim they bear the mandate of heaven, and the other side has been condemned by God to burn in Hell for all eternity. And they believe it. Ferociously. Soldiers who will die on impulse, who are willing to kill strangers, do so because they sincerely, passionately devote themselves to the honor and duty of their cause.

Tensions are high.

You think you hate journalists enough, but you don’t.

Journalists believe they are the most important people in the world, and so, of course, the American Civil War is told from the perspective of journalists seeking a story.

I get the sense this is not the movie Alex Garland wanted to make.

The movie he wants to make is a career-killer, and effectively illegal under the status quo, even if he could somehow finance and distribute that hypothetical movie — which he can’t.

Nobody is allowed to honestly discuss the compounding, accumulated problems of modern America — and the unresolved grievances of heartland America. Public figures who attempt to listen to the frustrations of the Midwest and Rustbelt are swiftly blacklisted.

Those Americans are forbidden from having a voice.

No Regime tolerates the aspirational depiction of an alternative future.

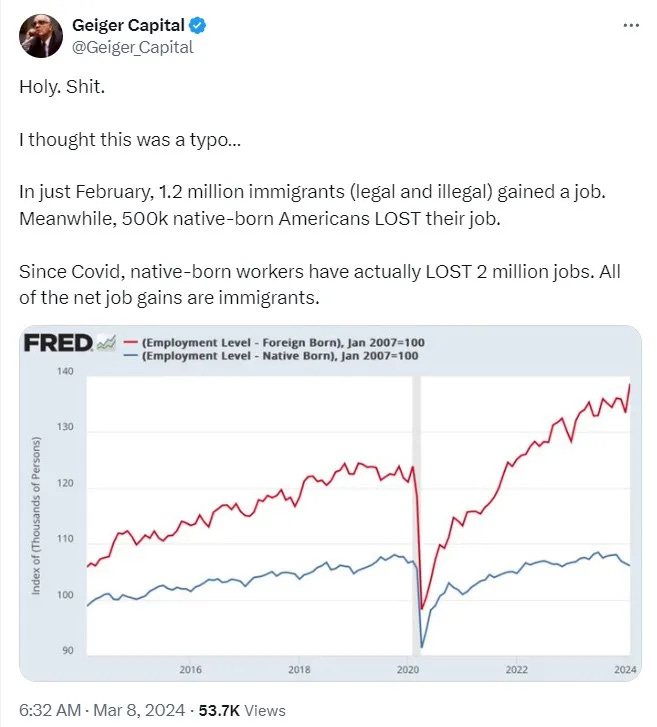

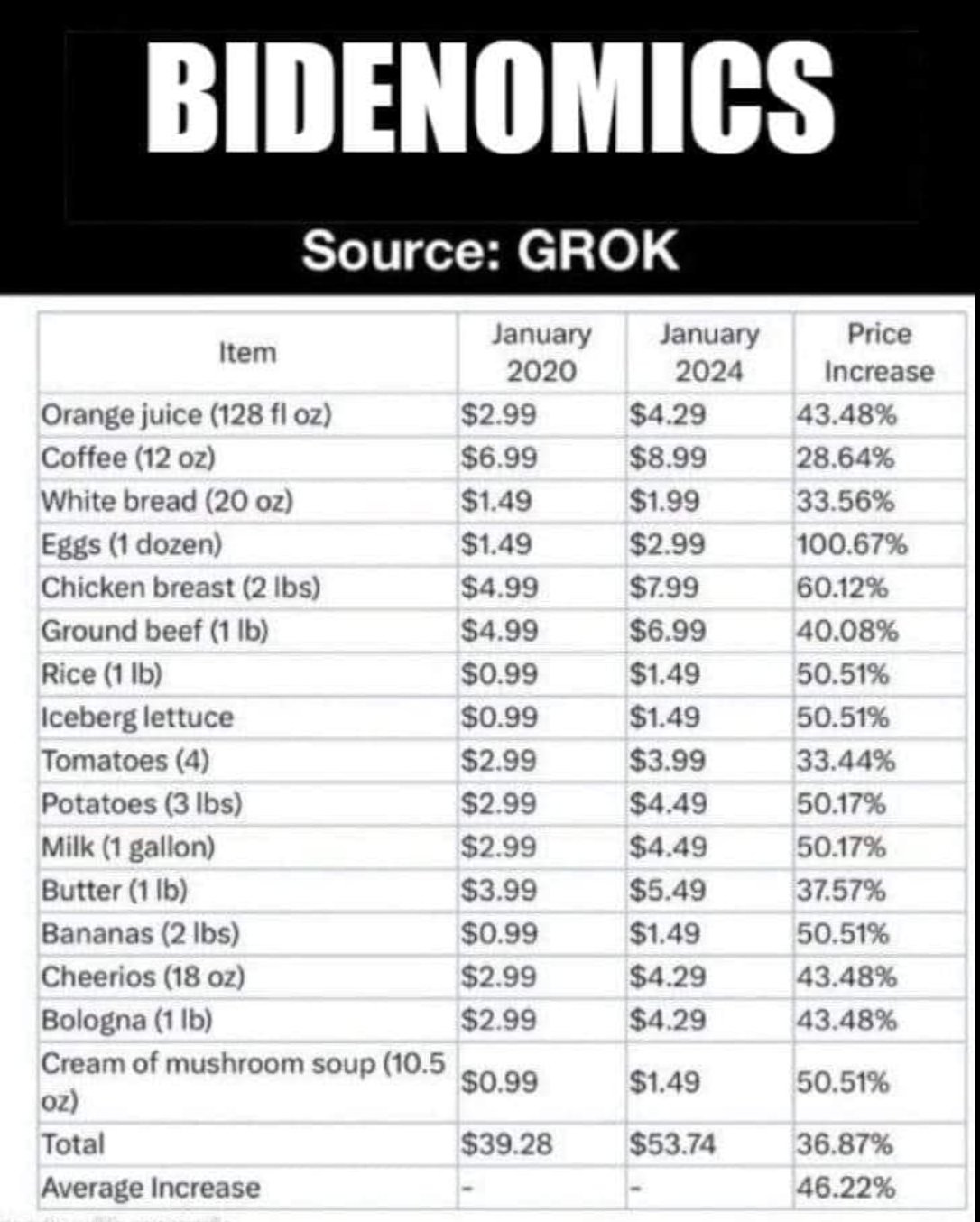

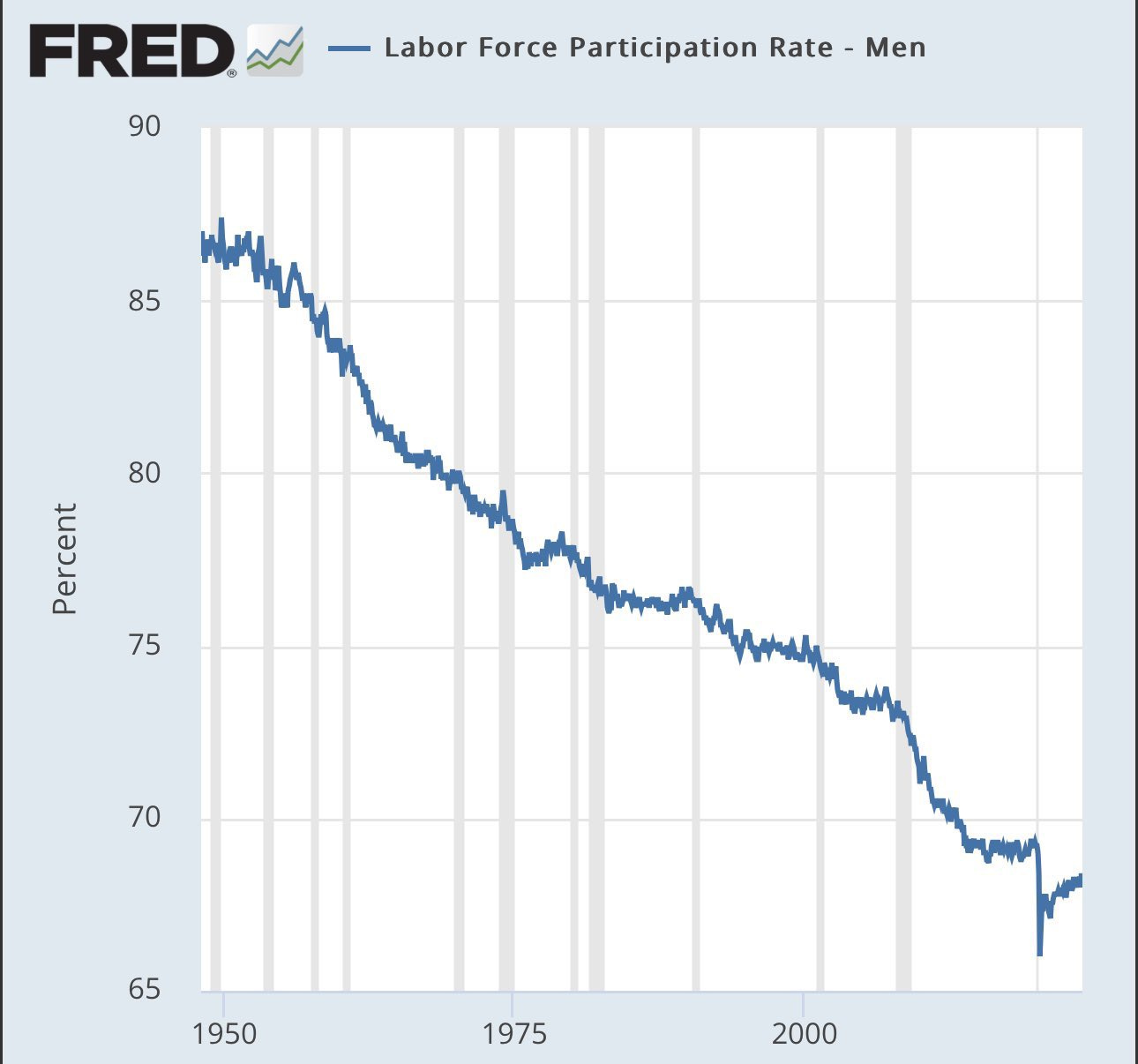

As discontent intensifies in modern America, citizenship has become an expensive burden, where even foreigners are treated better than native Americans.

In 1776, the Founding Fathers presented 27 grievances against the British King and Parliament.

Today, the list of American grievances might number around 270 problems which have been allowed to fester for decades.

In 1776, America was founded upon the Enlightenment theories of John Locke — that governments require consent of the people to retain sovereignty. And that, each generation must renew and renegotiate this social contract which is inherited from previous generations… because future generations cannot be enslaved by the obsolete traditions of dead, distant ancestors.

Or, as John Locke said:

“Men being, as has been said, by Nature, all free, equal and independent, no one can be put out of this Estate, and subjected to the Political Power of another, without his own Consent.”

—John Locke, Second Treatise

This viewpoint was explicitly announced in the first page of the Declaration of Independence:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed,—That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.”

—Declaration of Independence

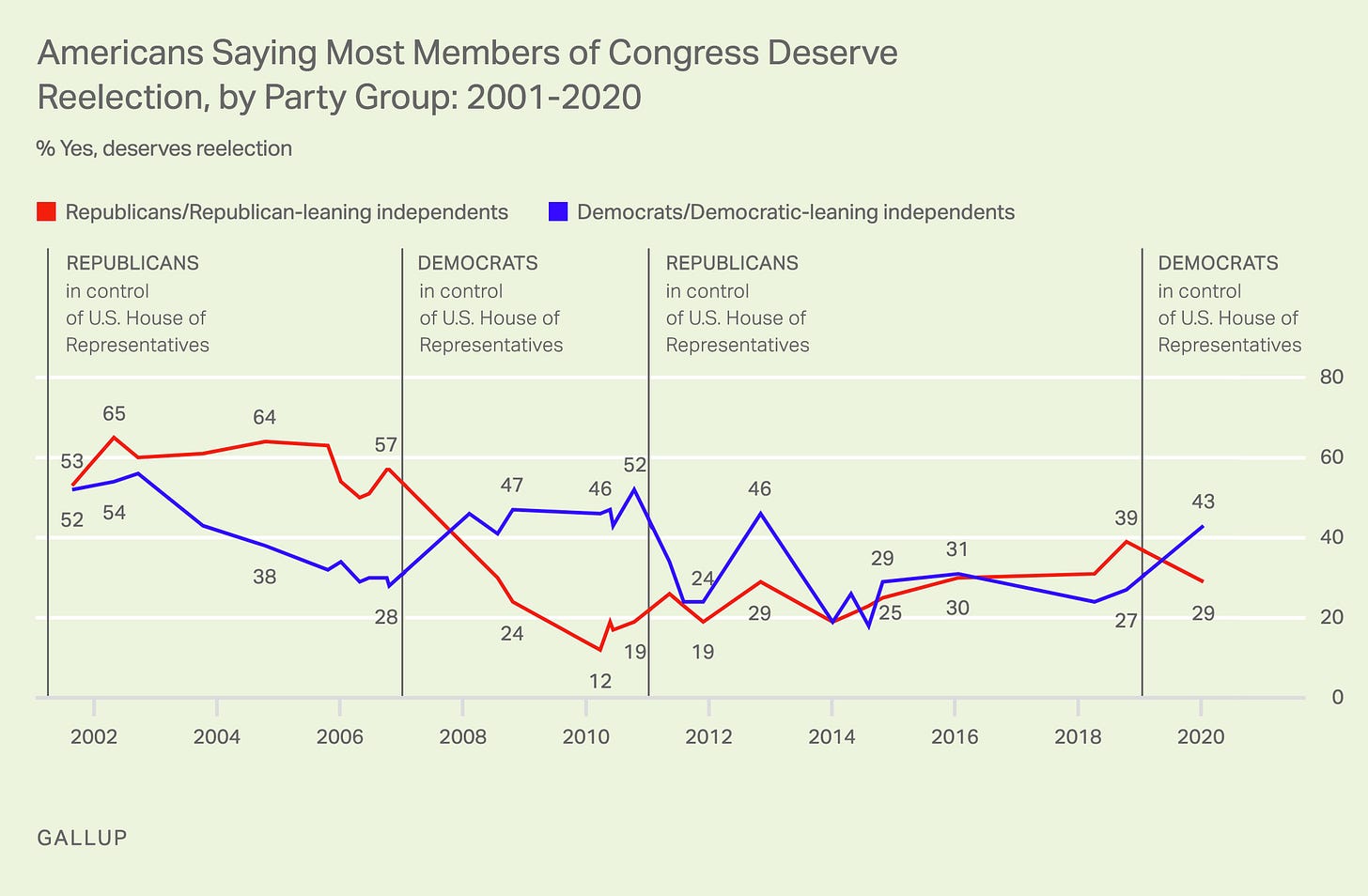

Joke polls have demonstrated Congress, the popularly-elected federal legislative body, is less popular than root canals, traffic jams, and various forms of STDs.

This is funny, but it also calls into question the true nature of government, when popular democracy has become overwhelmingly unpopular, and yet lifetime reelection of Congressmen glides along rates of 90%, which is comparable to the Soviet Politburo or the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party. A 30-point gap has emerged between what voters expect from the representative they are directly voting on, and the actual reelection rate.

Tucker Carlson, Joe Rogan Experience: Podcast Number 2138:

“What makes it particularly galling, and hard to live with, is when you call that system a democracy. That’s too dishonest for me. I would much rather live in a monarchy where everyone thinks that the king has been assigned by God to rule over us, and his whims are law. That makes sense. I don’t like it, but at least it has internal coherence.

When Congress stands up to pass a $60 billion funding bill for Ukraine, when seventy percent of the population doesn’t want it, when Congress is ignoring the actual problems in our country like the economy and the border, and they’re calling in Congress over the weekend to pass something that people don’t want, while ignoring the demands that people do want, and if Congress does the same kind of thing again and again and again for fifty years, and journalists call this system a democracy —that dishonesty will drive you insane.

Because it’s just too dishonest.

Why not just say: “We don’t give a shit what you want, we are getting something out of this Ukraine funding, whether it’s the thrill of being masters of the universe, or whether it’s money from the defense contractors, whatever we’re getting out of it, is more important to us than popular opinion, this is not self-government, ordinary people don’t run this country, we run this country, so shut up and obey” — if Congress at least said that, you would be like “okay, I get it, those are the terms”.

But if I get another fucking lecture from Joe Scarborough about defending democracy, when America is not a democracy, it’s not even a close approximation of a democracy, then I’m going to go crazy.

Because I just can’t deal with the lying anymore.

…

I guess what bothers me is that the lies aren’t sophisticated.

When I look back over my now-sort-of-long-life, and I recognize all the times I was previously deceived, you know I didn’t know I was being tricked. I wasn’t aware. They tricked me, and successfully pulled it off.

There’s something incredibly insulting and demeaning, to tell me something that’s a lie, and I know it’s a lie, and you know I know it’s a lie — we both know it’s a lie, and nonetheless you’re demanding that I pretend to believe it? What you’re really saying is: “I have no respect for you. You’re my slave. I’m demanding that you participate in my lie.”

The lack of stealth really bothers me a lot.”

—Tucker Carlson, Joe Rogan Experience: Podcast Number 2138

“Consent of the governed” seems more and more theoretical.

Alex Garland is a brilliant screenwriter, long fascinated by exotic concepts. He wrote The Beach, a thriller novel about a community of tourists in Thailand. He went on to a successful screenwriting career authoring the screenplays 28 Days Later, Sunshine, and Never Let Me Go. And he went on to a more elevated level of success as the writer and director of Ex Machina, and the director of Annihilation.

Alex Garland’s Civil War follows in this general vein, as a provocative and intriguing high-concept premise, which also functions as a timely and socially relevant reflection of contemporary anxieties — what if the unrest in America escalated to militarized secession? What if the incumbent government was destroyed by the rebels?

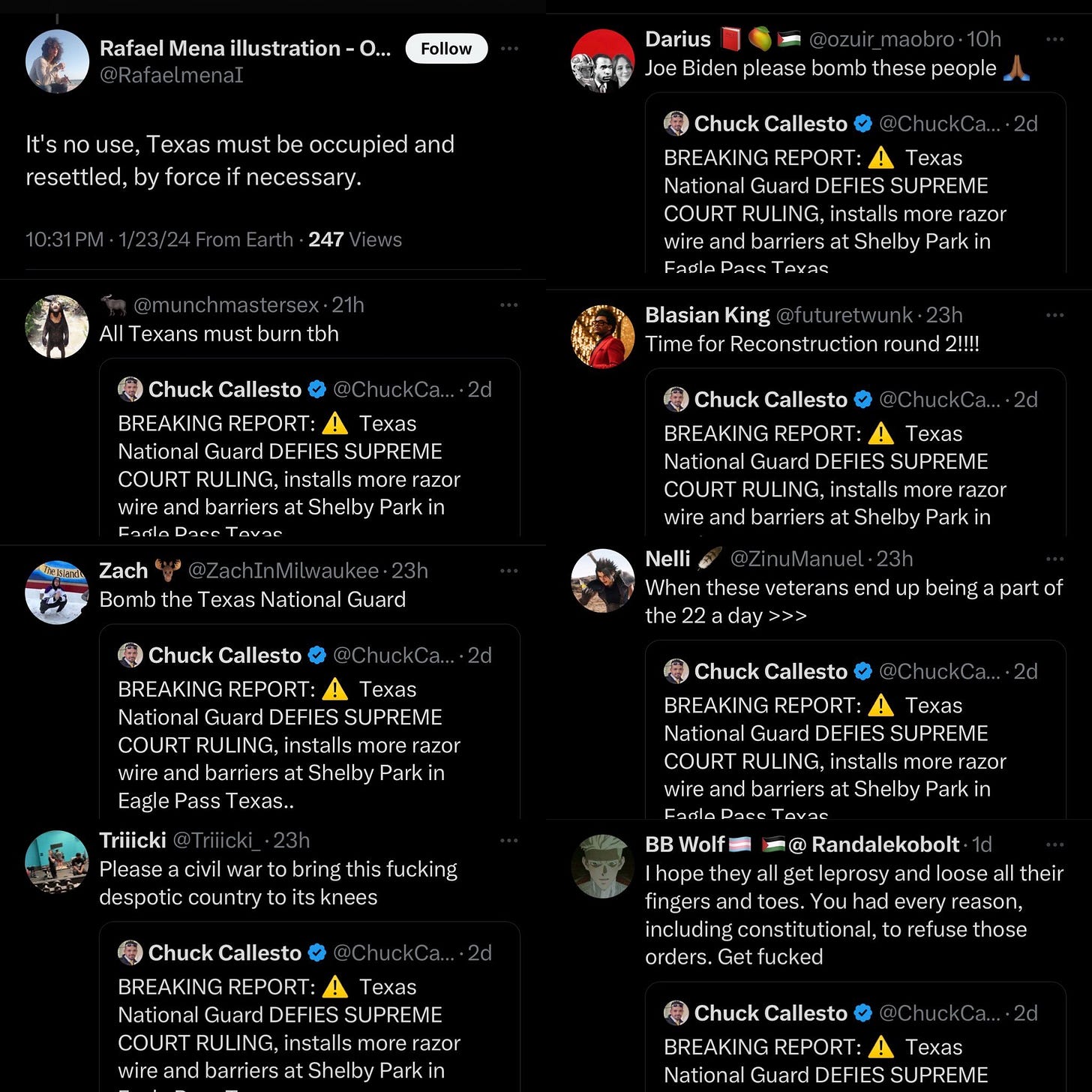

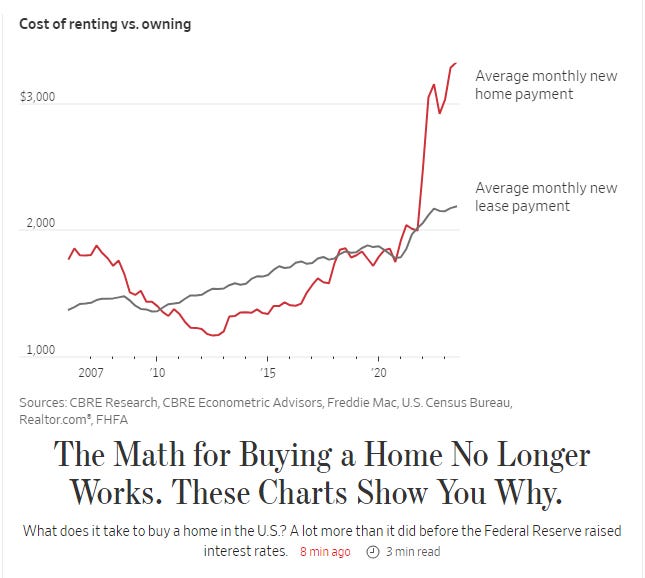

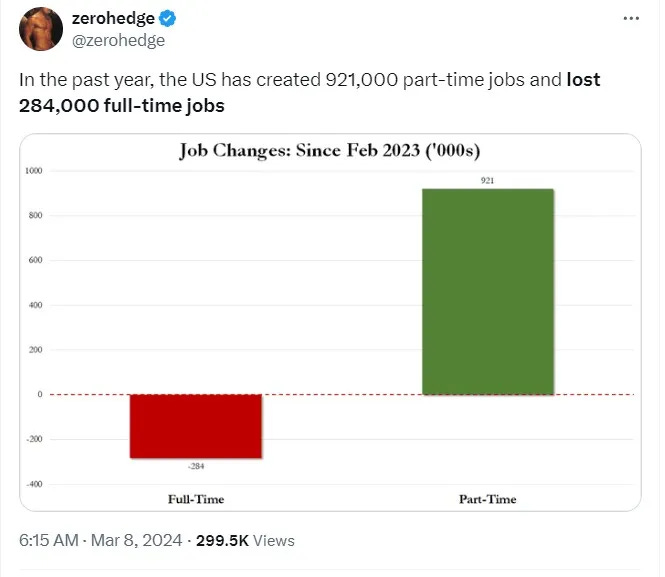

Real world tensions are already intense enough to unsettle casual observers.

Art is supposed to be honest.

Literature, or cinema, is supposed to express psychological truth — spiritual and metaphysical truth — rather than literal truth. When fictional characters learn and grow; struggle and transform; suffer and endure, their tribulations and travails should resonate so deeply with the audience that readers and moviegoers laugh; cry; cheer; love. Vicariously, audiences are inspired, and disturbed. From a distance, the story seems almost as if it happened to the audience themselves.

The problem with honestly exploring the possibility of an American Civil War is that both sides have their grievances, both sides have their humanity, and beautiful art demands that all of these multifaceted details be displayed and revealed fairly, if not evenly.

Elsewhere, some beautiful pieces have been written about this possible future:

There's Gonna be a War in Montana - by Isaac Simpson (carousel.blog)

The Second American Civil War - by Paul Fahrenheidt (substack.com)

But the Woke Regime refuses to change, unless the change is to intensify, escalate, and ACCELERATE Gay Race Communism.

There are no brakes on this train.

The problem Alex Garland faced as a screenwriter, director, artist, and social commentator was that he identified a clear, powerful market inefficiency in entertainment with immediate relevance to a broad audience — which is that political tensions in America are spiraling out of control, and this widespread anxiety is a strictly repressed social taboo. As a result, this topic has the potential to capture attention from tens of millions of Americans.

Lucrative rewards await.

His goal was to tap into this collective impulse, to somehow find a way to deliver emotional catharsis paired with philosophical insight and spiritual meaning, then profit, while building his career, clout, and connections.

The biggest obstacle to achieving this vision was to find a way to dance around the intensely suffocating censorship of the modern Regime.

You think you hate journalists enough, but you don’t.

Alex Garland used some exotic narrative solutions and techniques to bypass Woke objections. These methodologies will remain exotic, and unusual, because they effectively kill the entertainment value of the movie, by disobeying the basic principles of resonant narrative design.

To escape censorship, Alex Garland wrote the screenplay from the perspective of a team of four journalists who are recording the carnage and tragedy of a widespread civil war. Journalists are sacred cows in modern America, members of the Globohomo priesthood. In this film, the journalists are passive observers trapped in a much broader geopolitical conflict. They exert zero agency, have zero impact on the war, and don’t kill anyone during the course of the movie (other than hitting a gunman with a car in self-defense, after he kills two of their coworkers). Interestingly, the American President is described as dangerous because he murders all journalists — no other crime, ideology, or government policy is ever mentioned over the course of the movie.

Another basic rule of narrative structure is violated: In proper drama, the hero should be an underdog trapped in an impossible situation with a much stronger or smarter enemy, and the urgency of a ticking clock threatening the arrival or outbreak of some terrible crisis.

Instead, the war is completely one-sided, and the outcome of the conflict is never in doubt.

All of America assembles as secessionists to fight against the isolated and besieged capitol of DC. Near the end of the movie, the capitol city is abandoned by its surrounding allies, regional armies, and their generals, so that an outnumbered and outgunned Secret Service is forced to defend itself against the combined armies of Fifty States. California and Texas are allied part of the same political coalition, which bears zero resemblance to current Year America — but that’s exactly the point.

The ending battle is anticlimactic because there’s zero suspense, which is an intentional aesthetic choice.

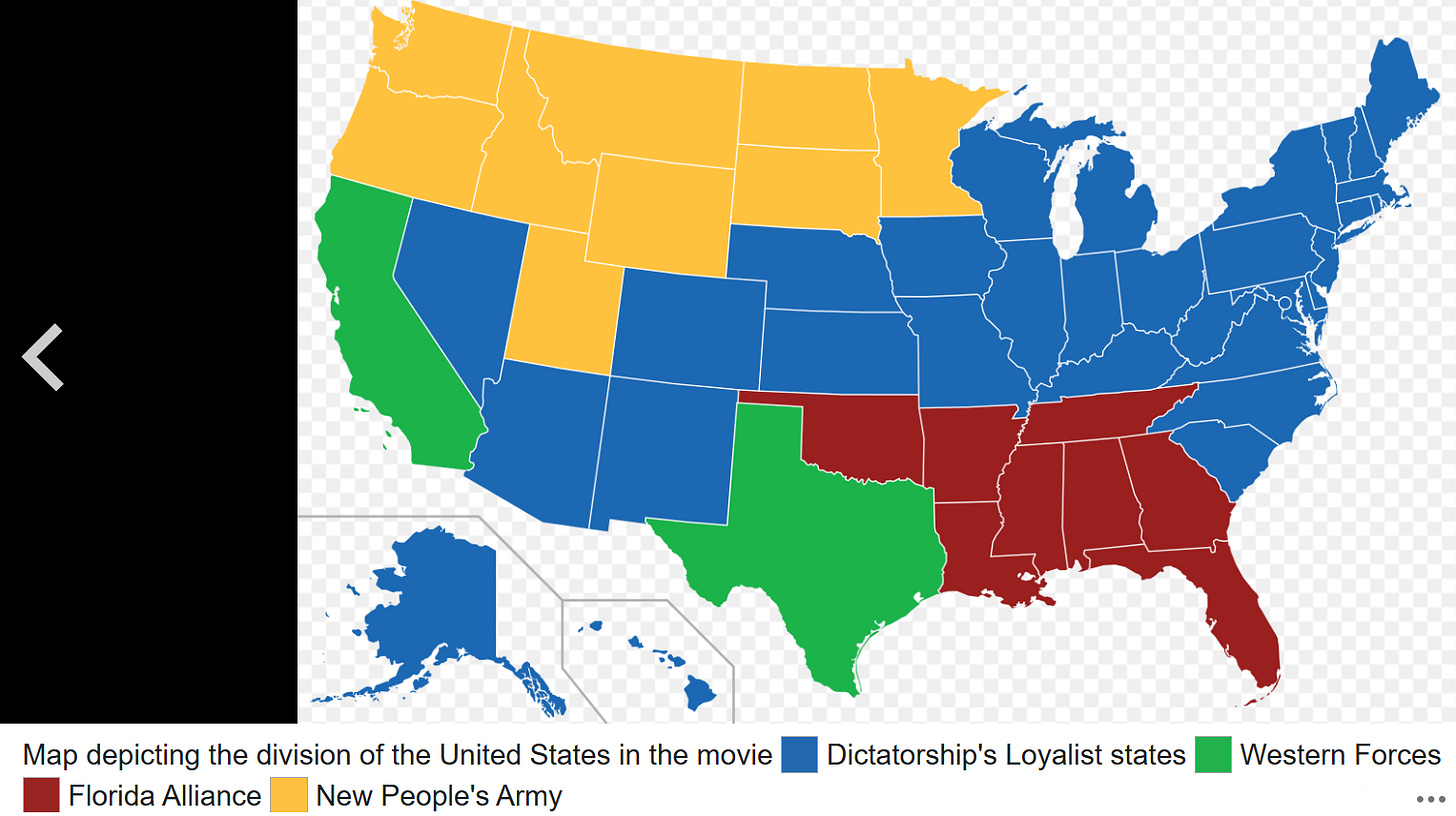

According to the film’s map, supposedly there are four political factions. But having watched the actual movie, I can tell you that there are only two which impact the story: the doomed city of Washington, DC — and everyone else, who are seceding. One of the journalists makes an offhand comment that after ransacking Washington, DC, the secessionist armies will splinter and turn against each other. Nothing in the movie supports this comment.

Finally, there is never any mention of what substance motivates the violent political divisions of this near-future America, or the cause of ideological fragmentation.

Wired Magazine comments:

“In Civil War, Garland’s apocalyptic US features a country ostensibly stripped of partisan labels, where both the left and right become intolerant of each other and turn deadly.

…

Garland’s argument that both sides are at fault, though, is disingenuous to the reality of the United States, both in 2020 when Garland wrote the script and even more so now, just months out from potentially the most consequential election in American history.

There is only one side calling for a “civil war.” There is only one side stoking hatred by spreading conspiracy theories about the Great Replacement. There is only one side boosting baseless and widely debunked theories that elections are rigged. There is only one side whose presidential candidate is promising a “bloodbath” if he loses the election.

For all its visual artistry — and there is plenty of that in this film — Garland has created a confused narrative that attempts to portray all sides as evil, with only the journalists at the center the real arbiters of truth. But in an age where extremists are ready and primed to decode and interpret any piece of media for their own ends, what Garland has really done is create a film in which these groups can see themselves on screen as the good guys.

Garland is well known for creating open-ended films that allow audiences to interpret the meaning in whatever way they want.”

—David Gilbert, Wired Magazine: "Alex Garland’s Civil War Plays Both Sides"

The frustration from establishment Libtard platforms here is amusing, but they are broadly correct that Alex Garland’s Civil War is a film which does its best to hide from the logical extrapolations of its own central dramatic premise. Journalists are theoretically scouts, collectors, curators, and distributors of information. But by narrowing his camera’s focus to the personal roadtrip of a van of journalists, Alex Garland makes a story so small that any hint of subversion or crimethink is prevented from endangering his own Hollywood career as an auteur, a rising star of the current studio system.

It’s a brilliant career move, but the result is a lackluster artistic product.

Alex Garland was presented with two immediate choices: tell an honest story about American tensions which would destroy his career, OR depict a dishonest affirmation of a corrupt status quo which would result in mediocre, forgettable art. Trapped between Scylla and Charybdis, he chose a third option — to incoherently ignore the subject at hand, while teasing and suggesting to audiences that important; provocative; timely epiphanies lurked around the corner.

The result is mediocre and forgettable, but has the virtue of refraining from the standard limpwristed denunciations of populism, fascism, and all of the other “isms” which have grown so tired in the bleeding, gasping organism of the Globohomo Imperial Leviathan.

To produce an apolitical movie about political conflict is something of a contradiction in terms, but we live in a contradictory, paradoxical age, so the confusion blends in well with the overall Clownworld ecosystem of vapid media entertainment.

Perhaps most surprising, there is no portrayal of Republicans, conservatives, QAnon, frogs, or MAGA Boomers.

Both sides of Alex Garland’s Civil War are in fact the dueling aspects of the Woke coalition.

The doomed, besieged President represents the anxiety of the Globohomo American Empire, and the global project of Gay Race Communism, which always feels precarious, perched on a dangerous ledge of geopolitical intrigues and domestic discontent — because the excesses and and aspirations of Bioleninist idealism are always running up against the limitations of propaganda, finance, and social consensus. As Curtis Yarvin wrote in 2008:

“You have to be a bit of a reactionary yourself to see the truth: these institutions are simply a matter of reality. So it is reality itself that progressivism attacks. Reality is the perfect enemy: it always fights back, it can never be defeated, and infinite energy can be expended in unsuccessfully resisting it.”

—Curtis Yarvin, An Open Letter to Open-Minded Progressives: Chapter 8: A Reset is not a Revolution

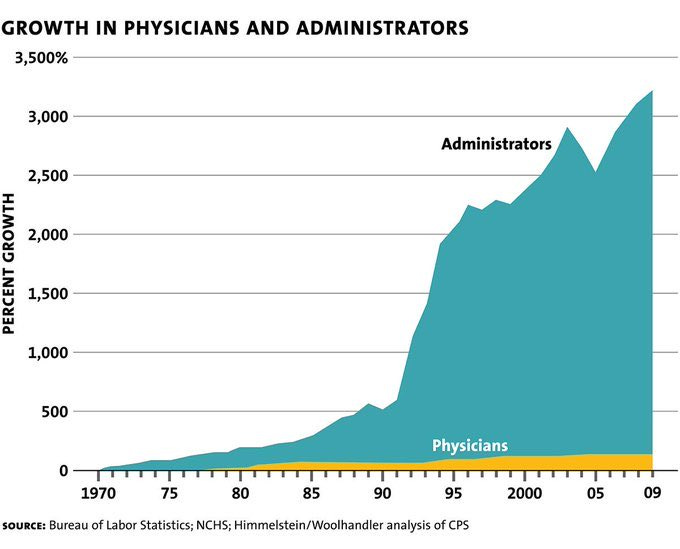

Progressives feel tired, so tired. They are trapped in the role of Sisyphus, forever pushing an enormous boulder up a hill, forever chasing the egalitarian destruction of all hierarchies everywhere, forever seeking to eradicate the invisible hand of white supremacy which causes disparate impact in the labor market and heterogenous outcomes in individual achievement, forever in denial of Pareto distributions and gender preferences, forever seeking to engineer a new form of life which will replace the imperfections of man.

The Utopia of Fully Automated Luxury Space Communism is a kind of Zeno’s Paradox; forever arriving, always close, seemingly inevitable, and yet it never finishes the journey.

In Alex Garland’s Civil War, the defeated President represents Woke anxiety — they are surrounded by enemies, they feel trapped, the situation seems hopeless.

Interestingly, the President himself is quite similar to Biden. He’s an irrelevant, powerless scapegoat who is trapped in his position. He has a big job title, and the ceremonial trappings of power, but lacks power itself. It seems to be a historical accident that he has found himself as the nominal boss of a weak, outgunned faction, and he has difficulty delivering the speeches which are written for him by other people. It's not clear this dictator character did anything to start the war, or ever committed a crime.

He is somewhat a hostage of his own position.

The secessionists are also Woke Libtards, and they embody the ambition of the contemporary American status quo. The soldiers are a multiethnic coalition of feminist women, gays, troons, whites, and they include every racial group. Their encampments are filthy tent cities and bombed-out favelas spread among the rubble of a decimated urban landscape. A black woman is included in the five-man kill team which storms the White House and assassinates the former American President — and she shoots an unarmed, white brunette Secret Service agent Girlboss who attempts to negotiate a peaceful surrender. Both sides are feminist Libtards who send women to fight and die along the front lines of the conflict. Both factions are cruel, nihilistic, vindictive, and merciless. There is no discernable ideological gap between the factions; this is a Bolshevik crusade against Mensheviks.

According to this film, the future will be proud, it will be gay, it will be Girlboss, and it will be ugly — the clothes, the architecture, especially the sanitation descend to third-world dysfunction and incompetence.

I expected a riveting, adventurous thriller where fictional characters struggled to win (or survive) a Civil War. Instead, this film presents a photojournalist’s search for an iconic photograph, which culminates in two memorable portraits.

There’s a nice literary aspect to this movie: Early on, a famous and seasoned Girlboss photojournalist mentors a young, aspiring camerawoman who reminds her of herself. In one of their early scenes, the young ingénue asks something along the lines of, “If I died, would you take a photo of me being shot?” Tired, and cynical, her mentor responds, “What do you think?” But at the end of the film, the young camerawoman stumbles out into the middle of a gunfight to grab a beautiful picture. She lines up to die in the crossfire, and her older, more cynical mentor leaps forward to push her to the ground, immediately being torn apart by gunfire. Quietly, coldly, the young photojournalist snaps her camera, capturing and preserving the death of her mentor.

True to life, the old generation of Leftist activists is gruesomely purged to feed the next generation of iconoclastic rebels… and someday their ideological children will devour them as well.

Imagine if the roles were reversed!

Cthulhu swims slowly, but he always swims left.

Eternal Revolution, comrades.

The young camerawoman stumbles forward, and she captures the iconic photograph which summarizes the end of the war — the execution of the American President, who dies on the floor of the White House, begging incoherently for mercy.

Funny enough, and again true to life, the photograph of the President’s execution is remembered, while the heroic and sacrificial death of the veteran photojournalist is forgotten.

Old Leftists are cast aside, desecrated.

Nobody remembers yesterday’s radicals.

And in similar fashion, this movie will soon be forgotten.

The year is 2044.

During the Second China Shock nearly all advanced manufacturing and other major industries were taken over by China. BYD crushed Tesla. China won the AI race.

To try to keep Chinese goods out tariffs were erected, but by relocating much production/assembly to mexico China was able to use nafta to get around this.

The Green New Deal and Chips Act also turned out to be major flops, but Mexico was immune to this as American became less competitive.

Meanwhile, boomer retirement and reckless spending caused a fiscal crises and China dumping treasuries wrecked the currency.

Demographic changes and Chinese backed Mexican economic strength caused Texas to flip blue in the 2030s.

Electorally this was offset by the entire rust belt flipping solid red as well as some places in the Mid Atlantic or Northeast turning against this Mexico/China alliance.

The western forces are Chinese/Mexican proxy agents and the end of the movie shows their victory in the proxy war. The United States will henceforth be a puppet state (or perhaps carved up). Perhaps promises of independence were what kept the Florida alliance on the sidelines (and clearly they allowed western forces through their territory).

Was expecting this movie to be about decrying Trump and the fascists supposedly poised to take over the country (what a ridiculous notion). It's fascinating that you say it takes a mostly apolitical stance. I strongly suspect there is a large contingent of people who would want an Alex Garland type civil war--where they can remain timidly apolitical and sit on the sidelines even as history moves forward, anything to avoid having to answer the hard questions.