“To avoid being a hack writer, hack away at your writing.”

—Michael R. Burch

“I’d rather have questions that can’t be answered, than answers that can’t be questioned.”

—Richard Feynman

Writing has an infinite skill ceiling.

There is always more to learn.

Even history’s most beloved writers had flaws, imperfections.

Reading the best stories of literary icons such as Homer, Victor Hugo, William Shakespeare, Ernest Hemingway, George R. R. Martin, Oscar Wilde, Charles Dickens, Jane Austen, Dante Alighieri, George Orwell, and J. R. R. Tolkien reveals a simple truth…

No artist is ever finished.

We can divide authors into two phylum: formally educated, versus self-taught autodidacts.

There are advantages and disadvantages to both schools.

Formally educated storytellers rise through the network of an entrenched patronage system, which reduces their emotional stress and financial strains. By working with mentors, editors, publicists, and salesmen, these formally educated artists learn how to be professionals. They learn discipline, media promotion, mechanics of compelling storytelling, and are forced to meet an impending deadline, which encourages them to adhere to a productive daily routine.

Huge benefits.

The downside of formal education is that these artists begin by learning how to do everything in the STANDARD manner. Often this encourages a rigid perspective on life, and more mechanical storytelling, which lacks the feeling of surprise, vulnerability, creativity, or authenticity.

Autodidacts are the opposite.

Being self-taught is a grueling uphill battle.

Everything is harder, nothing is easy. Loneliness and self-doubt plague the autodidact. He labors in profound isolation. But there is one huge benefit — nobody tells the Autodidact what he is supposed to be doing. Nobody burdens him with conventional wisdom. The autodidact spends the beginning of his career wandering in a barren, desiccated, unfriendly wilderness, thirsting for even the smallest of opportunities to quench his thirst, any slight validation to justify his delusional quest for personal excellence.

Most autodidacts die wandering this dry, arid wilderness, lost and forgotten, perishing before their career ever begins. The survival rate is extremely low. But the rare autodidacts who stumble out of the desert — bloodied, dehydrated, and delirious — are now in a special position.

They are unique.

Instantly an autodidact stands apart from the crowd.

When you read Quentin Tarrantino, J. K. Rowling, Philip K. Dick, Orson Welles, or Christopher Nolan, these icons are instantly different from anyone else.

It’s a mood.

A vibe.

Even if you don’t like their work personally, you recognize they are DIFFERENT.

The embodiment of Product Differentiation.

They don’t sound like their contemporaries. And they don’t repeat conventional patterns, or trends.

That matters. Unique storytellers are premium commodities in today’s crowded media landscape, which is oversaturated, yet desperate for original content.

The best artists combine both methods.

Memorable authors start in one camp, climb towards success, hit a plateau, struggle with stagnation, and then begin learning how to write differently. Either they are creative writers who need to learn disciplined structure, or they are disciplined artists who need to creatively abandon that structure.

(The previous sentence is an example of “Chiasmus”, which is relevant later.)

It’s a mental battle.

Identity shackles you to a habitual philosophy.

Improvement is a lifelong struggle, and it will never end. But we can still create profound, gorgeous art that expresses an eternal, aspirational message.

Everything meaningful in this world was achieved by imperfect men. We should begin by embracing and forgiving ourselves for our human imperfections.

Let’s talk about FrogTwitter,

FrogTwitter is full of dreamers: aspiring storytellers who swim amid the murky, digital swamp.

Passage Prize was an effective barometer for the current talent pool. Passage Prize revealed the good, the bad, and the ugly aspects of our community.

This literary contest revealed that the Frogs have enormous passion, but lack technical execution in terms of storytelling.

So, we must study technique.

Today, Billionaire Psycho is going to begin by teaching a very simple, easy lesson on how to write better prose.

All of you probably know the standard rhetorical devices that are taught in High School English: alliteration, allusion, analogy, foreshadowing, hyperbole, imagery, irony, metaphor, metonym, onomatopoeia, oxymoron, rhyme, simile, syllogism, and synecdoche.

I’m going to skip those lessons.

Edison Blake has been lurking on FrogTwitter for a couple years now, and during those months he read hundreds of essays by various frogs. The content was amazing. Magnetic, startling, and provocative. So many subversive, brilliant dissidents swim in these waters, and they are churning out fascinating material.

But most of this Dissident Content is carried by forceful ideas and riveting emotion (pathos), not the quality of their prose.

Some of the frogs are brilliant writers.

Lomez, Benjamin Braddock, and MedGold are excellent role models for writing essays — their prose is lean, efficient, purposeful, and well-structured. Their communication travels like one of Patton’s Sherman tanks during the North African Campaign — moves fast, hits hard, annihilates objections, and keeps rolling forward.

These are all beautiful examples of how to write a memorable, persuasive essay:

“Terrible Good Advice” by Benjamin Braddock

Terrible Good Advice › American Greatness (amgreatness.com)

“How the Lizard People Took Over America’s War” by Lomez

How the Lizard People Took Over America's War - The American Mind

“The Dark Path to Increasing the Birth Rate” by MedGold

The Dark Path to Increasing The Birth Rate (realmedgold.com)

When you read these essays, you will notice a similar pattern. Their essays adhere to a functional, efficient structure, as follows:

Title

Subtitle (optional)

Intro — 3 to 5 paragraphs

Subheading, with 3-5 paragraphs of content

(There are 3-5 subheadings, which provide the main body of the essay)

Conclusion, which ties back to the original thesis statement.

Very basic.

“Don’t get bored with consistency”.

Remember, the audience’s experience is different from the author’s. Your audience reads the essay once, and everything feels new to them. They are exploring an unfamiliar landscape created by an unseen puppeteer, a devious chessmaster.

After a dozen revisions, the childish joy of artistic creation often sours to a sense of nasty, frustrated self-loathing. Here, writers veer off-course. Sometimes they quit, abandoning a half-finished draft. The author is tempted to try some kind of exotic, experimental approach — a haphazard structure that produces a suboptimal outcome.

Again, I emphasize, “Don’t get bored with consistency.”

It takes intense discipline to repeat an optimal strategy, master a single method, and then to continually iterate… and iterate… and iterate upon narrow, focused execution, rather than tinkering with a proven design.

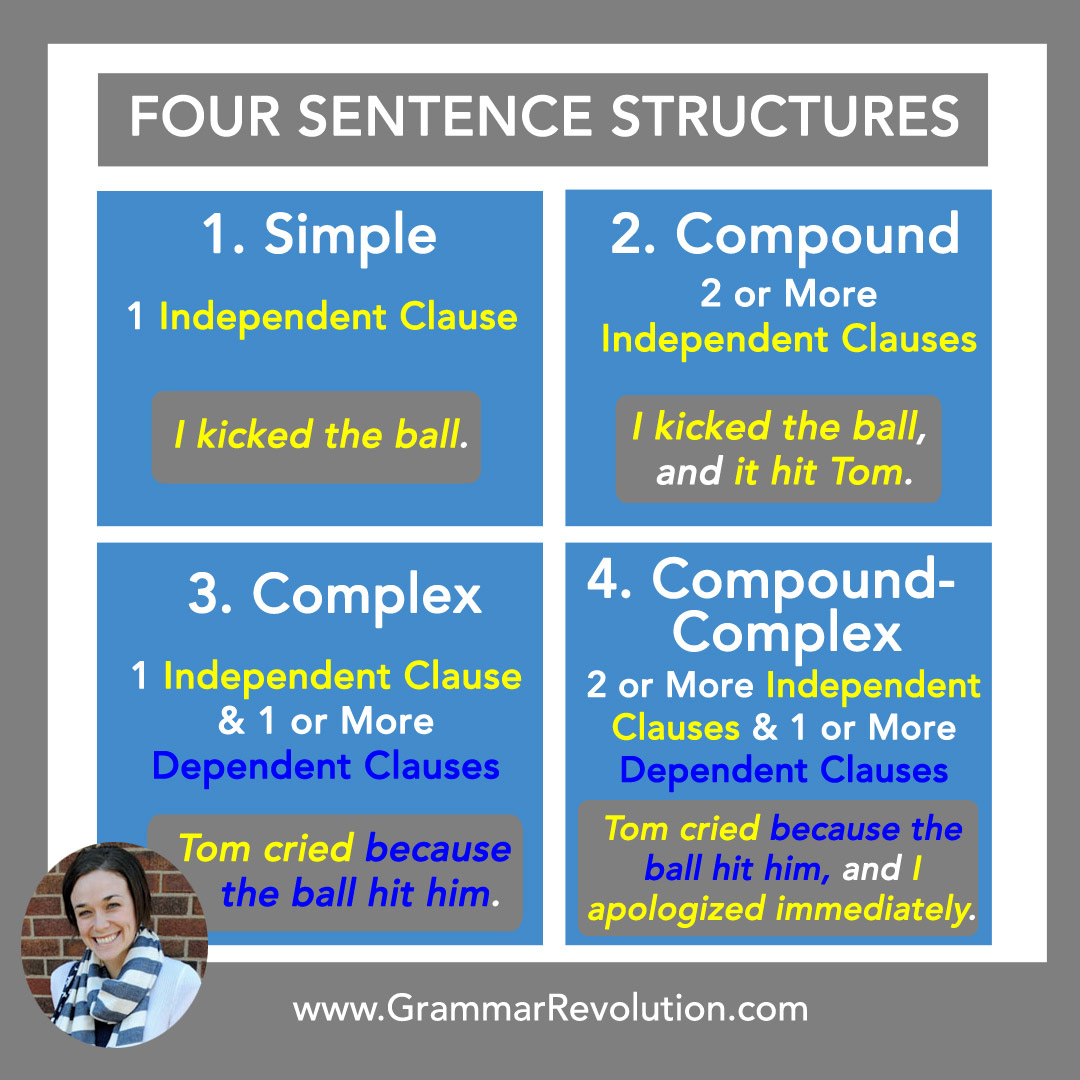

One of the most important techniques any writer should master is Sentence Structure.

This is where the frogs are weak.

Basic mechanics.

They write their blogs, narratives, and Substack articles in an inefficient, clumsy style. Knowing how to construct a proper sentence is a crucial skill — and the frogs were never taught these techniques.

Most of the frogs write in long-winded, rambling, complex sentences — exactly as they were taught during school, when they wrote essays that used excessive words to communicate a simple message. Their sentence structure tends to have one or two commas per sentence, which result in grammatical “compound”, “complex”, or “compound-complex” sentences.

Almost every sentence is longer than it needs to be.

Excess length piles up.

That’s bad.

Short sentences must be included between long paragraphs, functioning as brief interludes which allows the readers’ eyes to rest.

Your prose will improve dramatically.

When you master the art of writing, sentences ebb and flow like tides hitting the beach. Softly, slowly the waves roll against caramel-brown sand. The tide recedes. Then returns. And the waves caress the shoreline, dancing, brushing against crabs and bare feet of giggling children.

There’s a rhythm.

Long sentences follow short sentences.

Short sentences stand out. Brevity is easy to read.

Aphorisms punch HARD.

The author is a musician, and he plays with the tempo of the melody, accelerating and decelerating by altering the length of his sentences, modulating his use of commas, colons, semi-colons, dashes, ellipses, and italics. This variety delights the audience. Random patterns, combinations keep readers off-balance.

This is a simple concept, but it’s hard to train.

What I recommend is studying Chiasmus.

Chiasmus is very flashy, stylish, and rarely used. A notable gimmick. Learning this technique is not going to profoundly transform your writing, because even after you’ve mastered this skill, you will hardly ever use it.

But Chiasmus is the perfect technique for you to train, and refine your habitual sentence structure, because after you learn what it is, Chiasmus is extremely obvious.

It’s unforgettable.

And the problem with improving the sentence structure of your prose is that the sentences you write with are so automatic, you probably never think about it.

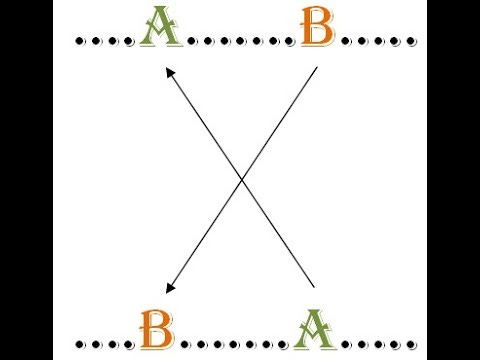

What is Chiasmus?

It’s a mirror technique, where you take a pair of two words, or ideas, and flip them.

Like so much else, Chiasmus comes from the ancient Greeks, based on their word “crossing”. This is because the structure of a Chiasmus can be diagrammed like an “X”.

Oral tradition has often featured the use of Chiasmus. Eloquent speakers from Jesus to John F. Kennedy mastered this tool, because it sounds really smart to the Normies when they hear a verbal reversal, plus Chiasmus is very easy to remember, and sometimes the reversal is able to express a profound truth.

Now, I’m going to repeat this concept to the point of redundancy and beyond, beating and bludgeoning a dead horse into the ground with famous examples of Chiasmus, because I intend to make this technique extremely obvious.

So, I say to any aspiring writers reading this: You must write three samples of Chiasmus after you finish this article. Any child could finish that task. Do the work. Enjoy the results. And this simple, easy exercise will build real skill. You will improve as a writer, and gain precision in your ability to craft a sentence.

40 Examples of Chiasmus:

1.)

“The greatest among you will be your servant. For those who exalt themselves will be humbled, and those who humble themselves will be exalted.”

—Matthew 23: 11-12

2.)

Many who are first will be last, and many who are last will be first.”

—Matthew 19:30

3.)

“Then he said to them, “The Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath.”

—Mark 2:27

4.)

“It is not the oath that makes us believe the man, but the man the oath.”

—Aeschylus

5.)

“Bad men live that they may eat and drink, whereas good men eat and drink that they may live.”

—Socrates

6.)

“One should eat to live, not live to eat.”

—Jean-Baptiste “Molière” Poquelin, The Miser

7.)

“It is not titles that honor men, but men that honor titles.”

—Niccolò Machiavelli

8.)

“The mind is its own place and, in itself can make a heaven of hell or a hell of heaven.”

—John Milton, Paradise Lost

9.)

“In peace sons bury their fathers, but in wars fathers bury their sons.”

—Croesus

10.)

“You were given a choice between war and dishonor. You chose dishonor, and now you will have war.”

—Winston Churchill, speaking to Neville Chamberlain

11.)

“You can take your boy out the hood, but you can’t take the hood out the homie.”

—Snoop Dogg

12.)

“If you can’t be with the one you Love, Love the one you’re with.”

—Billy Preston

13.)

“Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.”

—John F. Kennedy

14.)

“Mankind must put an end to war – or war will put an end to mankind.”

—John F. Kennedy

15.)

“Let us never negotiate out of fear, but let us never fear to negotiate.”

—John F. Kennedy

16.)

“It’s not the parts of the Bible I don’t understand that bother me, it’s the parts I do understand.”

—Mark Twain

17.)

“The difference between them and us is that we want to check government spending — and they want to spend government checks.”

—Ronald Reagan

18.)

“Foreign aid is taking money from the poor people of a rich country and giving it to the rich people of a poor country.”

—Ron Paul

19.)

A fine is a tax for doing wrong. A tax is a fine for doing well.”

—N.C. Chamber

20.)

“I don’t care how much you know until I know how much you care.”

—Teddy Roosevelt

21.)

“College: A place where some pursue learning, and others learn pursuing.”

—Anonymous

22.)

“Life imitates art far more than art imitates life.”

—Oscar Wilde

23.)

“When we are happy, we are always good, but when we are good, we are not always happy.”

—Oscar Wilde

24.)

“Woman begins by resisting a man’s advances, and ends by blocking his retreat.”

—Oscar Wilde

25.)

“A man’s face is his autobiography. A woman’s face is her work of fiction.”

—Oscar Wilde

26.)

“Men always want to be a woman’s first love; women want to be a man’s last romance.”

—Oscar Wilde

27.)

“I didn’t really say all the things I said.”

—Yogi Berra

28.)

“Laura, I don’t hate you because you’re fat. You’re fat because I hate you.”

—Mean Girls

29.)

“I’m not a writer with a drinking problem; I’m a drinker with a writing problem.”

—Dorothy Parker

30.)

“I wasted time, and now time doth waste me.”

—Shakespeare, Richard II

31.)

“I am stuck on Band-Aids, ‘cause Band-Aids stuck on me.”

—Mike Becker

32.)

It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.”

—Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes.

33.)

“Pleasure's a sin, and sometimes sin's a pleasure.”

—Lord Byron, Don Juan

34.)

“In infancy we learn to wrinkle our faces; in old age we learn to face our wrinkles.”

—Anonymous

35.)

“What’s right isn’t always popular; what’s popular isn’t always right.”

—Anonymous

36.)

“Never let a fool kiss you, or a kiss fool you.”

—Mardy Grothe

37.)

“An optimist laughs to forget; a pessimist forgets to laugh.”

—Anonymous

38.)

“Science without religion is lame. Religion without science is blind.”

—Albert Einstein

39.)

“I am a marvelous housekeeper. Every time I leave a man, I keep his house.”

—Zsa Zsa Gabor

40.)

“The purpose of life is a life of purpose.”

—Robert Byrne

Quite a lot of Chiasmus; the pattern should be quite obvious to my readers, and this technique serves as a useful introduction to mastering your sentence structure.

Amateur writers struggle with mastering the niceties of prose, because so much of their process is an automatic, unconscious mental process.

Chiasmus is a blatant gimmick that serves as an ideal primer to slow down that automatic process and consciously seize control of your prose.

Tomorrow I will be publishing another tranche of famous and witty Chiasmus that were gathered for this Lesson.

A nifty trick to make the trick-less nifty. Thanks for the education! Didn't know there was a name for this but I've seen it everywhere, as made obvious by your expansive selection of quotes.

for my next post on Nicomachean Exhortations, I'm looking to apply this.

'Those who listen to do, do well to listen.'

anybody here have better variations on this? I feel like its not clear enough yet. I'm trying to express that those that have the capability to act on wisdom are those that benefit in learning wisdom