“In Hollywood the screenplay is a fire hydrant with 300 dogs lined up around the block.”

—Frank Miller

“THE ILLUSION OF MOVEMENT

While the politics is playing out and the script is trying to gain creative support, it's important to keep the impression that all is proceeding smoothly. So the other purpose of notes and rewrites is to keep a project from seeming to be dead. It's not dead, see, there's a draft coming in, the writer is making fixes! This is a case where it is important to write quickly. The level of excitement and interest in a project is a real, tangible thing. A substantially late revision can kill the momentum of a project — simply by letting attention wander onto other projects.

SHOW BUSINESS

This took me a long time to figure out; stupid me. Very often, you're in a meeting working on a project at a company that is, in fact, not in the business of making movies. You might as well be hanging out shooting pool. How can that be? Doesn't it say Warner Bros., or DreamWorks, or MGM out there on the sign? Sure it does. But there's an ebb and flow to the entertainment business. Films are incredibly expensive — on average, fifty million to make and another fifty million to market. So films are not churned out by assembly line. Each one that happens, happens in a unique way.”

—Terry Rossio, Wordplayer: Hard Bargain

“The making of a picture ought surely to be a rather fascinating adventure. It is not; it is an endless contention of tawdry egos, some of them powerful, almost all of them vociferous, and almost none of them capable of anything much more creative than credit-stealing and self-promotion.

Hollywood is a showman's paradise. But showmen make nothing; they exploit what someone else has made.

…

To me the interesting point about Hollywood's writers of talent is not how few or how many they are, but how little of worth their talent is allowed to achieve. Interesting — but hardly unexpected, once you accept the premise that writers are employed to write screenplays on the theory that, being writers, they have a particular gift and training for the job, and are then prevented from doing it with any independence or finality whatsoever, on the theory that, being merely writers, they know nothing about making pictures, and of course if they don't know how to make pictures, they couldn't possibly know how to write them. It takes a producer to tell them that.

I do not wish to become unduly vitriolic on the subject of producers. My own experience does not justify it, and after all, producers too are slaves of the system.

…

Some are able and humane men and some are low-grade individuals with the morals of a goat, the artistic integrity of a slot machine, and the manners of a floorwalker with delusions of grandeur. In so far as the writing of the screenplay is concerned, however, the producer is the boss; the writer either gets along with him and his ideas (if he has any) or gets out. This means both personal and artistic subordination, and no writer of quality will long accept either without surrendering that which made him a writer of quality, without dulling the fine edge of his mind, without becoming little by little a conniver rather than a creator, a supple and facile journeyman rather than a craftsman of original thought.

It makes very little difference how a writer feels towards his producer as a man; the fact that the producer can change and destroy and disregard his work can only operate to diminish that work in its conception and to make it mechanical and indifferent in execution. The impulse to perfection cannot exist where the definition of perfection is the arbitrary decision of authority. That which is born in loneliness and from the heart cannot be defended against the judgment of a committee of sycophants.

…

There is no present guarantee that his best lines, best ideas, best scenes will not be changed or omitted on the set by the director or dropped on the floor during the later process of cutting—for the simple but essential reason that the best things in any picture, artistically speaking, are invariably the easiest to leave out, mechanically speaking.

…

The motion picture is a great industry as well as a defeated art.”

—Raymond Chandler, Writers in Hollywood

I.

Hollywood has humiliated many of the world’s greatest writers, and ignored the input of artists who were already household names in other mediums: F. Scott Fitzgerald, Vladimir Nabokov, Frank Miller, Raymond Chandler, Stephen Hunter, and William Faulkner. Each of these writers was scorned, rejected, and rewritten until his scripts were unrecognizable trash. Some raged. Some begged. Some bargained. But each man’s experience with the film industry culminated in bitter disappointment.

Cinema is a stubborn industry.

The film business is a low-trust society, which involves a Hobbesian war of all-against-all.

Every room is populated by vapid, charming social climbers… a coterie of beautiful, backstabbing sociopaths clawing desperately for creative control.

Writers tend to be naive, socially awkward daydreamers, and they usually fail in this kind of vicious, neurotic ecosystem.

Social consensus shreds introverted, thoughtful artists.

Ironically, some of the best stories have been written by demoralized, spiritually broken and financially desperate artists who spent years begging for Hollywood’s approval, persistently failed, eventually reached the point where they intensely despised movies, and then harnessed all the RAGE and SORROW and LUST and AMBITION of that pent-up creative energy into creating their masterpiece, their magnum opus.

Ernest Cline is a good example.

Ernest Cline wrote a decent, low-budget screenplay entitled “Fanboys”. He sold the script, and seemed to be the new golden boy. Soon problems began. For the next decade, he suffered through an agonizing cycle of revisions, sales pitches, and unforeseen obstacles. Always it seemed that success was waiting just around the corner. After many years of fruitlessly chasing dreams, he secured the support of George Lucas and (not yet disgraced) Kevin Spacey. A real budget arrived. Cameras started filming. Optimism stirred. False hopes blossomed. Then late into the process, an asshole director rewrote the script. Behind the scenes, a ferocious power struggle unfolded. The emotional core of the film was ripped out, and the subsequent final product was a vulgar, incoherent mess.

Ten years were wasted.

An entire decade of Ernest Cline’s life had been invested, and he had nothing to show for it — only an embarrassing, low-budget failure which grossed less than one million dollars.

But he didn’t quit.

Enraged, embittered, frustrated, saddened, stressed, desperate, frightened, Ernest Cline kept writing.

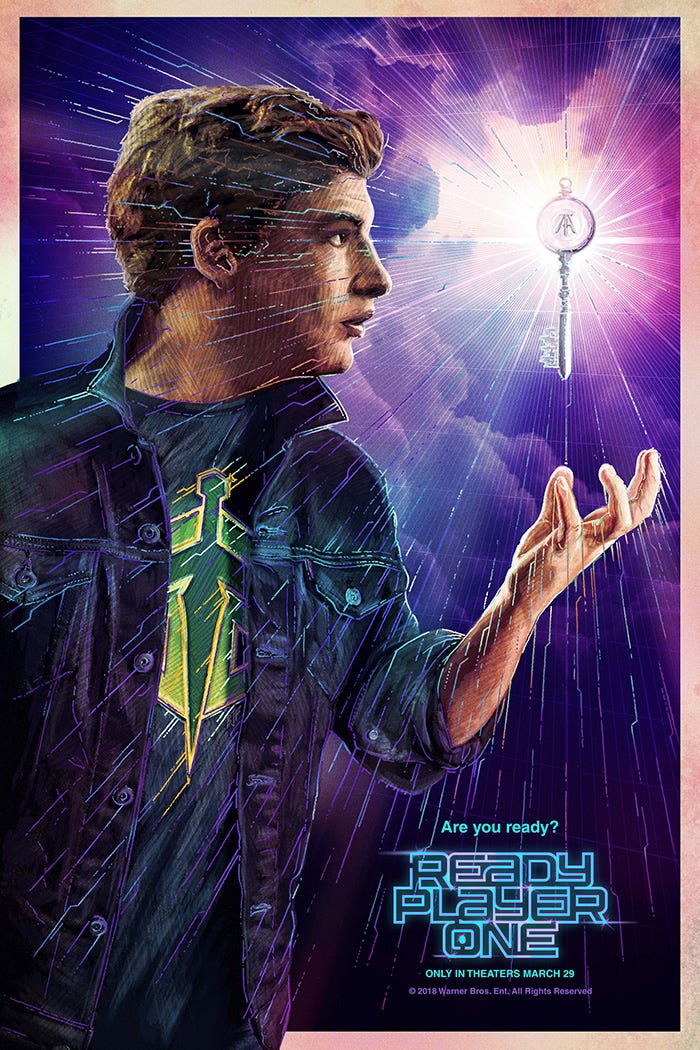

One year after the “Fanboys” disaster, Ernest Cline sold his debut novel, “Ready Player One” in an enthusiastic auction between publishing houses.

The book sold millions of copies.

Steven Spielberg adapted the novel into a blockbuster film, which grossed almost $600 million.

It seems like something out of a fairy tale.

An amazing comeback.

What happened was not an accident, or random luck — for ten years, Ernest Cline suffered through a brutal gauntlet of cruel, arbitrary revisions to his screenplay. He kept rewriting the same script to attract funding which promised to arrive, almost came, then was repeatedly denied. His life was trapped in a Kafkquesuqe bureaucracy of groveling absurdity… imprisoned in a spiritual purgatory of the cinema industry, perhaps as karmic punishment for the sins of a previous life. During this bleak, somber wasteland of meaningless suffering, Ernest Cline achieved two significant milestones: he improved as a storyteller, and he befriended an extensive network of professional contacts. He encountered actors, artists, directors, agents, producers, anyone who might be remotely useful in the future.

He kneeled and kissed the ring of anyone with a crumb of influence.

And it paid off, in a big way.

His debut screenplay was designed as a low-budget experimental vehicle. “Fanboys” was cheap, small, modest.

Unimpressive.

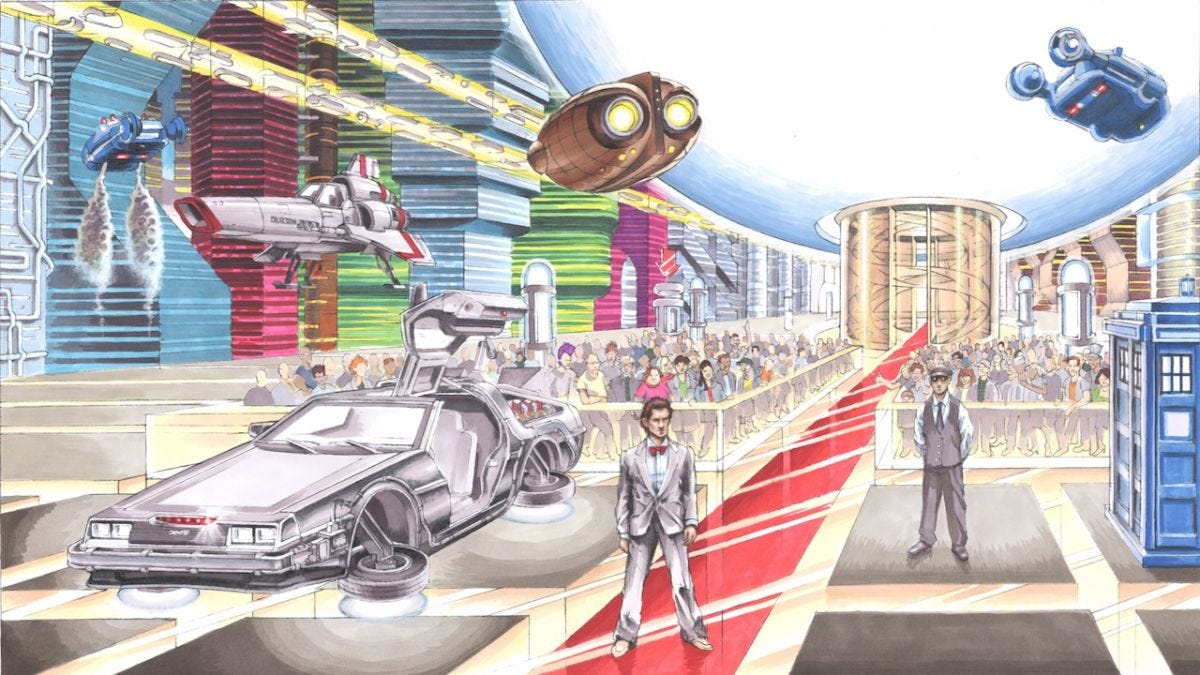

In contrast, his debut novel was a convoluted, epic quest through a dazzling world of retro arcade games, populated by thousands of characters, battling across dozens of impossible landscapes, enmeshed with subtle, sentimental Easter Eggs which provided a marketing gimmick; a narrative function; and alluded to a mostly-forgotten era of childhood delights.

Ready Player One was a rebellion.

A rebellion against Hollywood.

Screenplays impose strict discipline, precise time limits. Everything is limited by money. Background characters need costumes. Locations need to be scouted, rented, staged, filmed, and distorted with computer-generated illusions.

Operating within those constraints is an excellent way to learn the craft of writing.

Escaping these same constraints can deliver remarkable, exhilarating liberation — for the first time in years, Ernest Cline had the freedom to Dream BIG.

Freedom!

And for a brief time, he dreamed of something special.

Game of Thrones was born of the same rebellion, the same liberation; an embittered daydreamer escaping from the comfortable, suffocating prison of the film business.

Game of Thrones was invented as an explicit “fuck you” to Hollywood.

Like Ernest Cline, George R. R. Martin spent a frustrating decade in Hollywood, watching as his beloved screenplays were neutered, shackled, and lobotomized.

In 2011, George R. R. Martin explained that he designed the novel “A Game of Thrones” to be impossible to film, with so many characters, locations, costumes, equipment, stunts, and set pieces that it would bankrupt the budget of any studio which tried to produce it:

“I had worked in Hollywood myself for about 10 years, from the late ’80s to the ’90s. I’d been on the staff of The Twilight Zone and Beauty and the Beast. All of my first drafts tended to be too big or too expensive. I always hated the process of having to cut… I said, ‘I’m sick of this, I’m going to write something that’s as big as I want it to be, and it’s going to have a cast of characters that go into the thousands, and I’m going to have huge castles, and battles, and dragons.”

—George R. R. Martin

Elsewhere, he elaborates upon his frustrated, low-status years spent in Hollywood:

“He did like it. Not well enough to shoot my first draft, mind you (I soon learned that in Hollywood no one ever likes a script that much)…

I joined the series near the end of its first season, as a lowly Staff Writer (you know the position is lowly if the title includes the word ‘writer’)…

Casting, budgets, preproduction meetings, working with a director; all of it was new to me. My script was too long and too expensive. That would prove to be a hallmark of my career in film and television. All my scripts would be too long and too expensive.”

—George R. R. Martin, Dreamsongs: Volume 2: The Siren Song of Hollywood

Beautiful imagery is a huge part of what made “Ready Player One” and “A Game of Thrones” memorable.

These were vast, gorgeous adventures which seemed to explore expansive, vibrant landscapes.

Every medium has its own strengths, and shortcomings.

Films are stingy with time; the narrative must be compressed into 90 to 120 minutes, which provides a breathtaking, exhilarating pace at the price of predictability — the climax always arrives at the same part of the movie. Fans are familiar with every twist, every beat of the classic 3-Act Structure. The mythical hero’s journey is no longer surprising.

Comics are restricted to 22 pages per month. These serial narratives can be creatively choreographed, altering the size, number, perspective, and layout of panels, fusing or juxtaposing the combination of text and static images, pioneering visual art forms which have the potential to transform modern storytelling. But almost nobody reads them, so the commercial possibilities are stagnant. Lack of distribution cannibalizes the audience to a small, dependable audience of superhero fanboys.

Television delves into the psychological realism of characters, exploring the inner lives of heroes and villains with unparalleled depth. But each season threatens to be the last. At any point, a franchise might underperform and be killed by the studio. Precarious insecurity seeps in. Storylines are evaluated season by season. There’s a huge writer’s room collaborating together, but they are inventing, reinventing the show on a yearly basis. Nobody can plan for more than a couple years ahead. Sometimes the writers expect the show to end, they film a satisfying conclusion to the series, fans are thrilled, then ratings exceed expectations — and the studio extends the franchise for another season, after all the dramatic questions have already been answered. The next season is embarrassing, disappointing.

Every art form has a unique value proposition.

Each medium is a paradise. Each medium is a desolate, mud-stained ghetto. It just depends on how you choose to look at it… and what you’re trying to achieve, with the available tools.

Novels enjoy an infinite budget.

Writing a novel is free; all it takes is prolonged months of isolation, diligence, and careful architecture.

That’s a significant, asymmetric edge.

The canvas is as big as your imagination. Complex ideas can be explored at a gentle, methodical pace.

Other mediums feature imagery. But in books dreams can be made real, on an impossible scale.

There’s a certain irony that films are composed of transient images (and sounds), novels are composed of naked text… but screenwriters are better at writing dialogue, and novelists are better at describing images.

The contrast illuminates the nature of their work. Both professions learn to target absence, to create and simulate what does not exist, carefully disguising the empty vacuum yawning in the center of their medium… while leaning on the art form’s corresponding strengths. Both screenwriters and novelists tend to neglect what has been inherited from the medium itself, and never develop a relevant set of creative muscles.

Rarely do screenwriters try their hand at publishing novels; the results tend to be unprofitable, exhausting, and embarrassing. Awkwardly they stagger from chapter to chapter, scene to scene, writing transitions which skip from one camera angle to another.

But you can find countless examples of novelists writing bland, clunky, and inefficient dialogue — long, tedious paragraphs of philosophical sermons, mechanical exposition, and rambling soliloquies.

Good dialogue is short, fast, punchy. You don’t need to read a script’s dialogue in order to guess with remarkable accuracy whether the content is desirable. Normally, it’s enough to simply scan the page, and note the indentation. Long blocks of text are an automatic red flag. More than two sentences together is probably inefficient.

Keep dialogue succinct. This is a guideline, not a firm rule, but the heuristic is surprisingly reliable. One sentence is enough to communicate whatever a character needs to say. Then the conversation jumps to the next character. And perhaps back again.

Imagery offers exotic glimpses, to faraway landscapes.

Gorgeous vistas.

Painting a beautiful image in the minds of the audience taps into the latent wish fulfillment of the audience. A sense of glamor stirs…

The ambient thrill of adventure.

Some lovely descriptions are gathered below, which tend to emphasize four qualities: 1.) colors 2.) precise verbs which make the picture more vivid, more kinetic 3.) a sensory experience which delivers emotion, and 4.) the subject itself. Mountains, sunsets, oceans, castles, forests, canyons, skyscrapers, slums… all these settings can bring life, convey immersive depth to the narrative.

Imagery is one of the most powerful techniques available to a storyteller.

Novels are the most convenient medium to feature these sorts of striking, protracted descriptions. Then comics, and to a lesser extent, television and film.

One related question, which is not immediately obvious, is to ask: If Imagery is so great, so powerful, so beautiful and effective, then why is this technique not used in every story, in every scene? Are there any tradeoffs involved? What are the downsides of featuring lovely descriptions on a regular basis?

The problem is pacing.

Long descriptions slow the narrative.

Verbose documentation of color, terrain, and the interplay of shadows can undercut the dramatic momentum of a well-paced story.

I was surprised when I returned to Harry Potter, and reread J. K. Rowling’s first description of Hogwarts. Only two sentences describe the location. This introduction displays amazing brevity:

“The narrow path had opened suddenly on to the edge of a great black lake. Perched atop a high mountain on the other side, its windows sparkling in the starry sky, was a vast castle with many turrets and towers.”

—J. K. Rowling, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone: Chapter Six: The Journey from Platform Nine and Three-Quarters

The Hogwarts castle is such an important part of the Harry Potter series, but it was presented with a brief glance, and then the storyline hurried on.

I think this is a revealing example of one of Rowling’s most underrated strengths. She is consistently mocked for her politics, the stylistic quality of her prose, the naivete of her characters, and the logical inconsistencies of her world (all of the adults must behave as morons, in order for the heroic children to save the magical world at the end of each novel).

But one of her best qualities as a writer was the inhuman discipline applied to every scene, every chapter of the Harry Potter series.

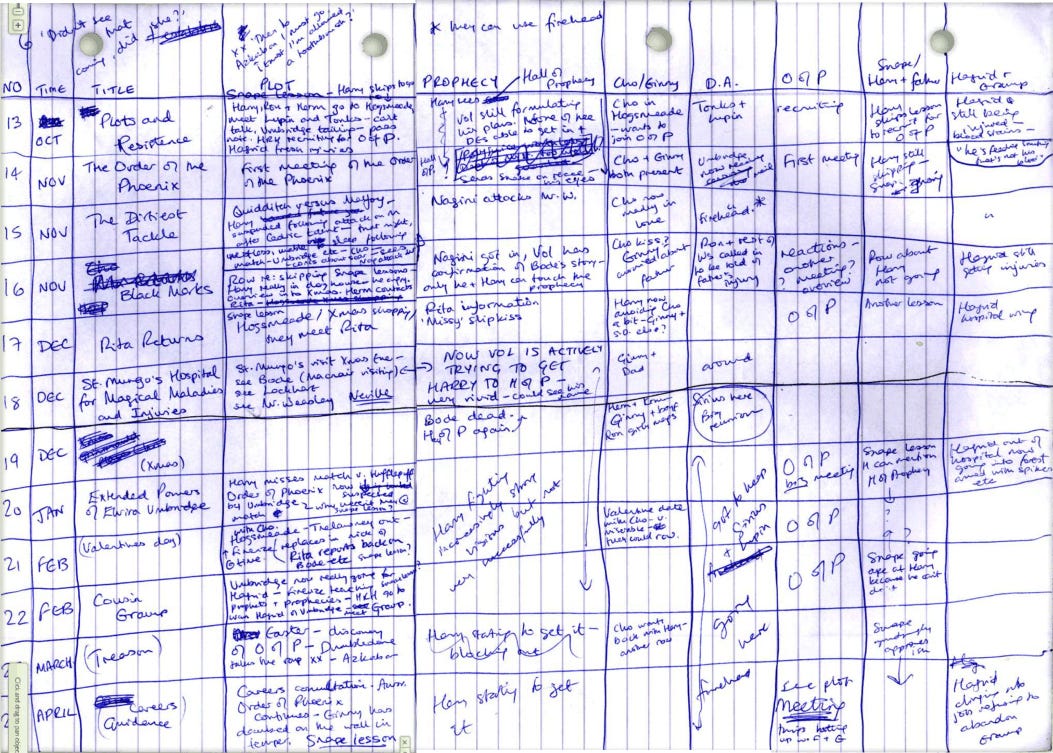

Rowling is clever and methodical in planting clues, intertwining subplots, and juggling a vast ensemble of supporting characters. She prepares herself for success by compiling elaborate, detailed rubrics which outline the character arcs, plots, and subplots that need to happen in each chapter.

This planning occurs long before the scene is written.

Rowling explains:

“I have a large and complicated chart propped on the desk in front of me to remind me what happens where, how, to whom and which bits of crucial information need to be slipped into which innocent-looking chapters.”

During the actual writing, J. K. Rowling progresses extremely quickly, and concisely, from one event to another. Key data is communicated in a single sentence, then the narrative glides to the next character.

Often her short chapters will feature three or four scenes, and each scene will sprinkle together three or four important bits of information, so that when readers arrive upon the end of a chapter, they have plunged into a dozen fresh events, ideas, clues, and curiosities to consider.

This is a great talent. And she makes it look simple.

So, to recap: Imagery is one of the most formidable techniques a writer can employ — but the downside is that too much description will drain momentum from the storyline.

Below are included some of my favorite examples, which I think are excellent models to study, dissect, and aspire towards:

1.)

“They go to each other’s bodies like those dying of thirst beside an oasis, plunging in again and again until their desire is relieved. For him it is ecstasy to see her beneath him on his bed, hair spread like a carpet of flowers, breasts heaved like hills, lips parted. She runs her hands all over him, she wants to touch ever muscle, feel the power behind his neck, cup his face beneath his jaw and pull him close where he is lost in her hair, floral with deep smells of crushed foliage; in his moments of release he sees endless glades, nameless shades of green, rolling hills, infinity.”

—Paulos MythPilot, Our Private Kingdom

Our Private Kingdom - by Paulos - Myth Pilot

2.)

“The rain was still falling, but the darkness had parted in the west, and there was a pink and golden billow of foamy clouds above the sea.”

—F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

3.)

“Cassie studied his face, the geometry of his cheekbones, his slate gray eyes and full lips that had entranced her; first in the nightclub fracas, through a whirlwind of vodka, sweat, pheromone sprays; and then in the back of an autocab; and then in the swaying stairwell to his apartment.”

—Rich Larson, Six Month Ocean

4.)

“Gotham City was cold shafts of concrete lit by cold moonlight, windswept and bottomless, fading to a cloudbank of city lights, a wet, white mist, miles below me. The streets were a soft, sad roar, unbroken and unchanging.”

—Frank Miller, Batman: Year One, The Deluxe Edition (1988), Preface

5.)

“The power is off again; she storms down the hall towards me, a frenetic silhouette backlit by the reflected light of distant fires.”

—Peter Watts, Bethlehem

6.)

“It was the aural equivalent of an island archipelago seen from the air — a chain of low humps broken by broad swaths of blue.”

—Stephen King, Misery

7.)

“The sun drifted down behind the trees, dappling the grass with shadows, and the blue of the sky deepened to a luminous aqua.”

—Lev Grossman, The Magicians

8.)

“A year here and he still dreamed of cyberspace, hope fading nightly. All the speed he took, all the turns he’d taken and the corners he’d cut in Night City, and still he’d see the matrix in his sleep, bright lattices of logic unfolding across that colorless void…”

—William Gibson

9.)

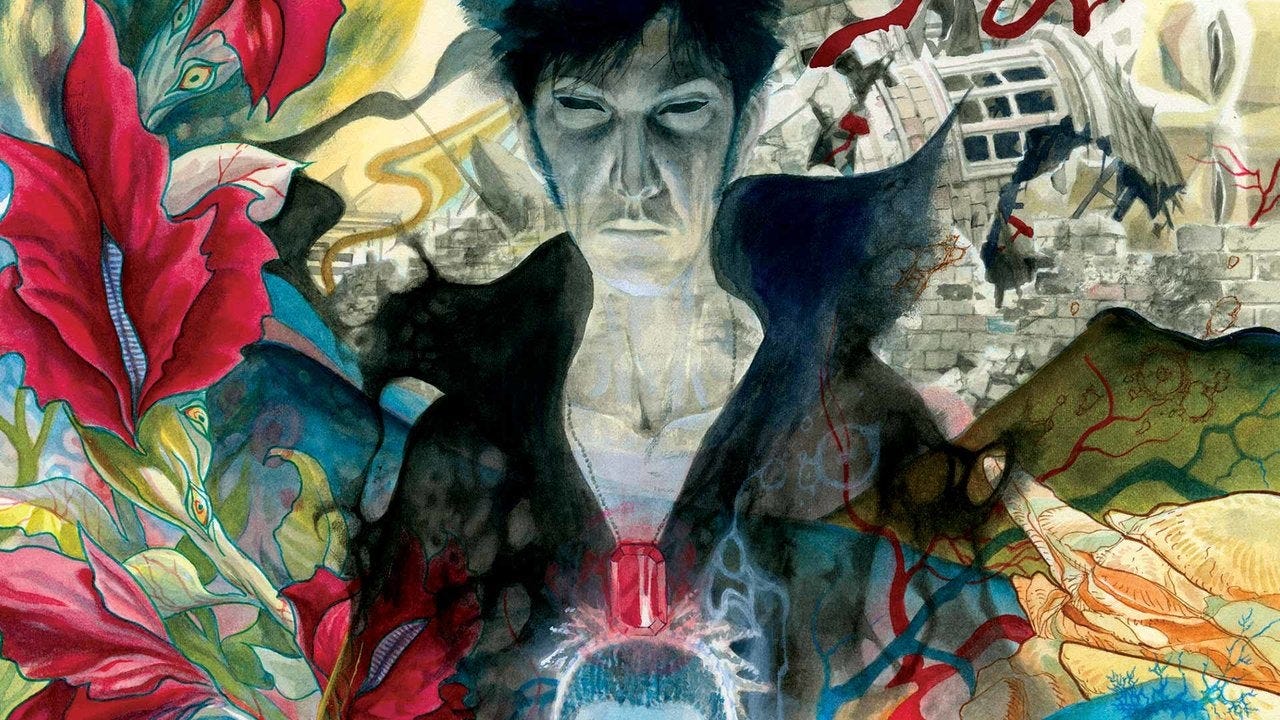

“The King of Dreams had skin as pale as the winter moon and hair as black as a raven’s wing, and his eyes were pools of night inside which distant stars glittered and burned. His robe was the colour of night, and flames and faces appeared in the base of it and were gone. He began to speak, in a voice that was gentle, yet strong as silk.”

—Neil Gaiman, The Sandman: The Dream Hunters

10.)

“There were car gods there: a powerful, serious-faced contingent, with blood on their black gloves and on their chrome teeth: recipients of human sacrifice on a scale undreamed-of since the Aztecs. Even they looked uncomfortable. Worlds change.”

—Neil Gaiman, American Gods

11.)

“The street was still. Brooked by canyons of white limestone facades and shimmering blue-glass skyscrapers, it looked like a film set at night, a giant model of a world no real people occupied.”

—Dennis Lehane, Gone, Baby, Gone

12.)

“The sky was a canvas of explosive colors. Whites, reds, blues, even some orange and yellow. A clap of thunder rocked the room and a starburst of blue and white ignited the sky. A shooting star of red rocketed through the middle and set off a smaller starburst that bled all over the blue and white. The whole display hit its peak then collapsed at once, the colors arcing downward and sputtering out in a cascade of dying embers.”

—Dennis Lehane, A Drink Before the War

13.)

“The deep green pool of the Salinas River was still in the late afternoon. Already the sun had left the valley to go climbing up the slopes of the Gabilan mountains, and the hilltops were rosy in the sun. But by the pool among the mottled sycamores, a pleasant shade had fallen.”

—John Steinbeck, Of Mice and Men

14.)

“She wore that day a pretty print dress that I had seen on her once before, ample in the skirt, tight in the bodice, short-sleeved, pink, checkered with darker pink, and, to complete the color scheme, she had painted her lips and was holding in her hollowed hands a beautiful, banal, Eden-red apple.”

—Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita

15.)

“The night had washed out to a soft blue gloom that was creeping over the buildings beside us like a bleach stain on the darkness.”

—Richard K. Morgan, Altered Carbon

16.)

“The icy sidewalk glinted like new marble, and the wind was dark and gray as slush.”

—Dennis Lehane, Animal Rescue

17.)

“Autumn. A full moon floated over old Edo, behind the thinnest haze of high cloud. It shone like a geisha’s night-lamp through an old mosquito net. The sky was antique browned silk.”

—Bruce Sterling, Flowers of Edo

18.)

“The houses were left vacant on the land, and the land was vacant because of this. Only the tractor sheds of corrugated iron, silver and gleaming, were alive; and they were alive with metal and gasoline and oil, the disks of the plows shining.”

—John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath

19.)

“Another cliff jutted out into the water about thirty yards ahead, effectively cutting off the shore, and to the right of it, out in the ocean, Teddy saw an island he hadn’t even known was there. It lay under the moonlight like a bar of brown soap, and its grip on the sea seemed tenuous.”

—Dennis Lehane, Shutter Island

20.)

“As the sun cascaded through the hazy sky, beams of light drained like spilled paint across the western horizon. Looking at the lacquered lake suffused with deep orange, garnet, and magenta, I stood by the shore for several moments, watching two sunsets collide.”

—Blake Crouch, Desert Places

21.)

“The Wall was still awesome to behold. Seen from orbit, it was a pale, circular ring on the surface of Mars, two thousand kilometres wide. Like a coral atoll, it entrapped its own weather system: a disc of bluer air flecked with creamy white clouds that stopped abruptly at the boundary.”

—Alastair Reynolds, Galactic North

22.)

“The Duke Leto Atreides leaned against a parapet of the landing control tower outside Arrakeen. The night’s first moon, an oblate silver coin, hung well above the southern horizon. Beneath it, the jagged cliffs of the Shield Wall shone like parched icing through a dust haze. To his left, the lights of Arrakeen glowed in the haze — yellow... white... blue.”

—Frank Herbert, Dune

23.)

“Further and further into the wastes she led him, till he saw the wide plains give way to low hills, marching upward in broken ranges. Far to the north he caught a glimpse of towering mountains, blue with the distance, or white with the eternal snows. Above these mountains shone the flaring rays of the borealis. They spread fan-wise into the sky, frosty blades of cold flaming light, changing in color, growing and brightening.

Above him the skies glowed and crackled with strange lights and gleams. The snow shone weirdly, now frosty blue, now icy crimson, now cold silver. Through a shimmering icy realm of enchantment Conan plunged doggedly onward, in a crystalline maze where the only reality was the white body dancing across the glittering snow beyond his reach — ever beyond his reach.”

—Robert E. Howard, Gods of the North

24.)

“Instead of the holographic blue, the dome was now full of stars. It was like no view I’d ever seen from another station or ship. There were furious blue-white stars embedded in what looked like sheets of velvet. There were hard gold gems and soft red smears, like finger smears in pastel. There were streams and currents of fainter stars, like a myriad neon fish caught in a snapshot of frozen motion. There were vast billowing backdrops of red and green cloud, veined and flawed by filaments of cool black. There were bluffs and promontories of ochre dust, so rich in three-dimensional structure that they resembled an exuberant impasto of oil colours; contours light-years thick laid on with a trowel. Red or pink stars burned through the dust like lanterns. Orphaned worlds were caught erupting from the towers, little sperm-like shapes trailing viscera of dust. Here and there I saw the tiny eyelike knots of birthing solar systems. There were pulsars, flashing on and off like navigation beacons, their differing rhythms seeming to set a stately tempo for the entire scene, like a deathly slow waltz. There seemed too much detail for one view, an overwhelming abundance of richness, and yet no matter which direction I looked, there was yet more to see, as if the dome sensed my attention and concentrated its efforts on the spot where my gaze was directed. For a moment I felt a lurching sense of dizziness, and—though I tried to stop it before I made a fool of myself—I found myself grasping the side of the table, as if to prevent myself from falling into the infinite depths of the view.”

—Alastair Reynolds, Beyond the Aquila Rift

25.)

“Oh, if Pa would only come home! She could not endure the suspense another moment She looked impatiently down the road again, and again she was disappointed. The sun was now below the horizon and the red glow at the rim of the world faded into pink. The sky above turned slowly from azure to the delicate blue-green of a robin's egg, and the unearthly stillness of rural twilight came stealthily down about her. Shadowy dimness crept over the countryside. The red furrows and the gashed red road lost their magical blood color and became plain brown earth. Across the road, in the pasture, the horses, mules and cows stood quietly with heads over the split-rail fence, waiting to be driven to the stables and supper. They did not like the dark shade of the thickets hedging the pasture creek, and they twitched their ears at Scarlett as if appreciative of human companionship.

In the strange half-light, the tall pines of the river swamp, so warmly green in the sunshine, were black against the pastel sky, an impenetrable row of black giants hiding the slow yellow water at their feet. On the hill across the river, the tall white chimneys of the Wilkes, home faded gradually into the darkness of the thick oaks surrounding them, and only far-off pin points of supper lamps showed that a house was here. The warm damp balminess of spring encompassed her sweetly with the moist smells of new-plowed earth and all the fresh green things pushing up to the air.

Sunset and spring and new-fledged greenery were no miracle to Scarlett. Their beauty she accepted as casually as the air she breathed and the water she drank, for she had never consciously seen beauty in anything but women's faces, horses, silk dresses and like tangible things. Yet the serene half-light over Tara's well-kept acres brought a measure of quiet to her disturbed mind. She loved this land so much, without even knowing she loved it, loved it as she loved her mother's face under the lamp at prayer time.

Still there was no sign of Gerald on the quiet winding road.”

—Margaret Mitchell, Gone with the Wind

26.)

“The Dothraki sea,” Ser Jorah Mormont said as he reined to a halt beside her on the top of the ridge. Beneath them, the plain stretched out immense and empty, a vast flat expanse that reached to the distant horizon and beyond. It was a sea, Dany thought. Past here, there were no hills, no mountains, no trees nor cities nor roads, only the endless grasses, the tall blades rippling like waves when the winds blew. “It’s so green,” she said.

“Here and now,” Ser Jorah agreed. “You ought to see it when it blooms, all dark red flowers from horizon to horizon, like a sea of blood. Come the dry season, and the world turns the color of old bronze. And this is only hranna, child. There are a hundred kinds of grass out there, grasses as yellow as lemon and as dark as indigo, blue grasses and orange grasses and grasses like rainbows. Down in the Shadow Lands beyond Asshai, they say there are oceans of ghost grass, taller than a man on horseback with stalks as pale as milkglass. It murders all other grass and glows in the dark with the spirits of the damned. The Dothraki claim that someday ghost grass will cover the entire world, and then all life will end."

—George R. R. Martin, A Game of Thrones

27.)

“The cliffs ahead were a bright, liquid gold. Strips of shadow were lengthening in the valleys below. The sun was descending to the peaks in the west. They were going west and up, toward the sun.

The sky had deepened to the greenish-blue of the rails, when they saw smokestacks in a distant valley. It was one of Colorado's new towns, the towns that had grown like a radiation from the Wyatt oil fields. She saw the angular lines of modern houses, flat roofs, great sheets of windows. It was too far to distinguish people. In the moment when she thought that they would not be watching the train at that distance, a rocket shot out from among the buildings, rose high above the town and broke as a fountain of gold stars against the darkening sky. Men whom she could not see, were seeing the streak of the train on the side of the mountain, and were sending a salute, a lonely plume of fire in the dusk, the symbol of celebration or of a call for help.

Beyond the next turn, in a sudden view of distance, she saw two dots of electric light, white and red, low in the sky. They were not airplanes '—she saw the cones of metal girders supporting them—and in the moment when she knew that they were the derricks of Wyatt Oil, she saw that the track was sweeping downward, that the earth flared open, as if the mountains were flung apart—and at the bottom, at the foot of the Wyatt hill, across the dark crack of a canyon, she saw the bridge of Rearden Metal.”

—Ayn Rand, Atlas Shrugged

28.)

“Every night, regularly, at nine, at twelve, at three, they lifted a nocturnal song, a weird and eerie chant, in which it was Buck’s delight to join.

With the aurora borealis flaming coldly overhead, or the stars leaping in the frost dance, and the land numb and frozen under its pall of snow, this song of the huskies might have been the defiance of life, only it was pitched in minor key, with long-drawn wailings and half-sobs, and was more the pleading of life, the articulate travail of existence. It was an old song, old as the breed itself — one of the first songs of the younger world in a day when songs were sad. It was invested with the woe of unnumbered generations, this plaint by which Buck was so strangely stirred. When he moaned and sobbed, it was with the pain of living that was of old the pain of his wild fathers, and the fear and mystery of the cold and dark that was to them fear and mystery. And that he should be stirred by it marked the completeness with which he harked back through the ages of fire and roof to the raw beginnings of life in the howling ages.”

—Jack London, Call of the Wild

29.)

“Ice had frozen on the rock and the myriad of icicles among the conifers glistened blood red in the reflected light of the sunset spread across the prairie to the west. He sat with his back to a rock and felt the warmth of the sun on his face and watched it pool and flare and drain away dragging with it all that pink and rose and crimson sky. An icy wind sprang up and the junipers darkened suddenly against the snow and then there was just stillness and cold.”

—Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian

30.)

“As they came to the opening in the wood, they were surprised to see knights in bright mail and tall guards in silver and black standing there, who greeted them with honour and bowed before them. And then one blew a long trumpet, and they went on through the aisle of trees beside the singing stream. So they came to a wide green land, and beyond it was a broad river in a silver haze, out of which rose a long wooded isle, and many ships lay by its shores.”

—J. R. R. Tolkien, The Return of the King

31.)

“Then the sky would begin to bleed behind them, high cirrus clouds turning purple, rust, crimson, lavender, and then swiftly to metal shavings, in a rosy sky; and the incredible fountain of the sun would pour over some rocky rim or scarp, and they would search anxiously as they ghosted over the pocked and shadowed landscape, looking for some sign of an airstrip by the piste. After the eternal night it seemed impossible that they would have navigated successfully to anything at all, but there lay the gleaming piste below, which they could land on directly in an emergency. And the transponders being all individually identifiable, and pegged to the map, their navigation was always more sure than it seemed; so every dawn they would spot a strip down in the shadows ahead, a welcome blond pencil strip of perfect flatness. Down they would glide, thump against the ground, slow down, taxi to whatever facilities they could find; stop the engines, slump back in the seats. Feel the strange lack of vibration, the stillness of another day.”

—Kim Stanley Robinson, Red Mars

32.)

“Something odd was happening to the tank, where Sunday had tapped it. Ripples of colour raced away from that one spot: pinks and greens, blues and golds. The ripples vanished from sight, scurrying into the ground. They came back in blotches of solid colour, spreading like inkblots but not mixing together. The colours flickered and pulsed, then settled down into the same muddy red tones as the tank’s surroundings.”

—Alastair Reynolds, Blue Remembered Earth

33.)

“The snow fell in her hair and glistened white for just a moment before it melted and disappeared.”

—Dennis Lehane, Darkness, Take My Hand

34.)

“Snow was falling in the San Saba when they crossed it and snow was falling on the Edwards Plateau and in the Balcones the limestone was white with snow and he sat watching out while the gray flakes flared over the windshield glass in the sweep of the wipers. A translucent slush had begun to form along the edge of the blacktop and there was ice on the bridge over the Pedernales. The green water sliding slowly away past the dark bankside trees. The mesquites by the road so thick with mistletoe they looked like liveoaks. The driver sat hunched up over the wheel whistling silently to himself. “

—Cormac McCarthy, All the Pretty Horses

35.)

“It was that time of the year, the turning-point of summer, when the crops of the present year are a certainty, when one begins to think of the sowing for next year, and the mowing is at hand; when the rye is all in ear, though its ears are still light, not yet full, and it waves in gray-green billows in the wind; when the green oats, with tufts of yellow grass scattered here and there among it, droop irregularly over the late-sown fields; when the early buckwheat is already out and hiding the ground; when the fallow lands, trodden hard as stone by the cattle, are half ploughed over, with paths left untouched by the plough; when from the dry dung-heaps carted onto the fields there comes at sunset a smell of manure mixed with meadow-sweet, and on the lowlying lands the riverside meadows are a thick sea of grass waiting for the mowing, with blackened heaps of the stalks of sorrel among it.”

—Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina

36.)

“The shadow of the pyramid’s tip had come to touch the road; now the sky in the west changed from the orange of a riptide bonfire to that cauldron of blood Roland had seen in his dreams ever since childhood. When it did, the call of the Tower doubled, then trebled. Roland felt it reach out and grasp him with invisible hands. The time of his destiny was come.”

—Stephen King, The Dark Tower

37.)

“The density of information overwhelmed the fabric of the matrix, triggering hypnagogic images. Faint kaleidoscopic angles centered into a silver-black focal point. Case watched childhood symbols of evil and bad luck tumble out along translucent planes: swastikas, skulls and crossbones dice flashing snake eyes. If he looked directly at that null point, no outline would form. It took a dozen quick, peripheral takes before he had it, a shark thing, gleaming like obsidian, the black mirrors of its flanks reflecting faint distant lights that bore no relationship to the matrix around it.”

—William Gibson, Neuromancer

38.)

“And as I sat there brooding on the old, unknown world, I thought of Gatsby’s wonder when he first picked out the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock. He had come a long way to this blue lawn, and his dream must have seemed so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it. He did not know that it was already behind him, somewhere back in that vast obscurity beyond the city, where the dark fields of the republic rolled on under the night.”

—F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

39.)

“Chords, vibrations, and harmonic ecstasies echoed passionately on every hand, while on my ravished sight burst the stupendous spectacle of ultimate beauty. Walls, columns, and architraves of living fire blazed effulgently around the spot where I seemed to float in air, extending upward to an infinitely high vaulted dome of indescribable splendor. Blending with this display of palatial magnificence, or rather, supplanting it at times in kaleidoscopic rotation, were glimpses of wide plains and graceful valleys, high mountains and inviting grottoes, covered with every lovely attribute of scenery which my delighted eyes could conceive of, yet formed wholly of some glowing, ethereal plastic entity, which in consistency partook as much of spirit as of matter. As I gazed, I perceived that my own brain held the key to these enchanting metamorphoses; for each vista which appeared to me was the one my changing mind most wished to behold. Amidst this elysian realm I dwelt not as a stranger, for each sight and sound was familiar to me; just as it had been for uncounted eons of eternity before, and would be for like eternities to come.”

—H. P. Lovecraft, Beyond the Wall of Sleep

40.)

“Sharla’s lush sensualism meshed perfectly with the romantic aura of the city. On clear days they would stroll the side streets and boulevards, stopping for lunch at whatever bistro or café might capture their interest; and when it rained, as it did often that summer, they would curl up in the comfortable apartment for long, languid days of fire and flesh, with the unseasonable hazy chill of Paris outside the windows a perfect backdrop to their passion. Jeff wrapped his fears in Sharla’s sleek black hair, hid his undiminished confusion in the folds of her sweet-scented, supple body.

She looked across the table at him with an impish gleam in her eye, and devoured the plump strawberry in one carnal bite. A thin trickle of the bright red juice colored her lower lip, and she wiped it slowly away with one slender, long-nailed finger.”

—Ken Grimwood, Replay

41.)

“They crested the mountain at sunset and they could see for miles. An immense lake lay below them with the distant blue mountains standing in the windless span of water and the shape of a soaring hawk and trees that shimmered in the heat and a distant city very white against the blue and shaded hills. They sat and watched. They saw the sun drop under the jagged rim of the earth to the west and they saw it flare behind the mountains and they saw the face of the lake darken and the shape of the city dissolve upon it. They slept among the rocks face up like dead men and in the morning when they rose there was no city and no trees and no lake only a barren dusty plain.”

—Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian

42.)

“I walked her home, against the wind, snow flying everywhere, helping her rewrap her red knitted scarf once, twice, and on the third time, I was tucking her in properly and our faces were close, and her cheeks were a merry holiday-sledding pink, and it was the kind of thing that could never have happened in another hundred nights, but that night it was possible. The conversation, the booze, the storm, the scarf.

We grabbed each other at the same time, me pushing her up against a tree for better leverage, the spindly branches dumping a pile of snow on us, a stunning, comical moment that only made me more insistent on touching her, touching everything at once, one hand up inside her sweater, the other between her legs. And her letting me.

She pulled back from me, her teeth chattering. ‘Come up with me.’

I paused.

‘Come up with me,’ she said again. ‘I want to be with you.’”

—Gillian Flynn, Gone Girl

43.)

“Prodigy was the word that took him from his parents’ home to a house in a deep deciduous forest where winter was savage and violent and summer a brief desperate eruption of green. He grew up cared for by unsinging servants, and the only music he was allowed to hear was birdsong, and windsong, and the crackling of winter wood; thunder, and the faint cry of golden leaves as they broke free and tumbled to the earth; rain on the roof and the drip of water from icicles; the chatter of squirrels and the deep silence of snow falling on a moonless night.”

—Orson Scott Card, Unaccompanied Sonata

44.)

“I’ll remember how the sunrise felt there on patrol. How bright the stars were as we pulled security at night (I have never seen so many!). Then as we prepared for Stand-To, as the Army has done since back when it was fighting the French and the Indians, the darkness softened to gray, then yielded to sunrise, and you clung to the fading coolness as you watched the merciless sun take its sweet time getting into position to torment you and your buddies for the rest of the day.”

—Samuel Finlay, Requiem for the ‘Stan

https://im1776.com/2021/08/20/requiem-for-the-stan/

45.)

“One day — after a longer than usual gestation period — Zima unveiled a mural that had something different about it. It was a picture of a swirling, star-pocked nebula, from the vantage point of an airless rock. Perched on the rim of a crater in the middle distance, blocking off part of the nebula, was a tiny blue square. At first glance it looked as if the canvas had been washed blue and Zima had simply left a small area unpainted. There was no solidity to the square; no detail or suggestion of how it related to the landscape or the backdrop. It cast no shadow and had no tonal influence on the surrounding colours. But the square was deliberate: close examination showed that it had indeed been overpainted over the rocky lip of the crater. It meant something.”

—Alastair Reynolds, Zima Blue

46.)

“‘So I travelled, stopping ever and again, in great strides of a thousand years or more, drawn on by the mystery of the earth’s fate, watching with a strange fascination the sun grow larger and duller in the westward sky, and the life of the old earth ebb away. At last, more than thirty million years hence, the huge red-hot dome of the sun had come to obscure nearly a tenth part of the darkling heavens. Then I stopped once more, for the crawling multitude of crabs had disappeared, and the red beach, save for its livid green liverworts and lichens, seemed lifeless. And now it was flecked with white. A bitter cold assailed me. Rare white flakes ever and again came eddying down. To the north-eastward, the glare of snow lay under the starlight of the sable sky, and I could see an undulating crest of hillocks pinkish white. There were fringes of ice along the sea margin, with drifting masses further out; but the main expanse of that salt ocean, all bloody under the eternal sunset, was still unfrozen.”

—H. G. Wells, The Time Machine

47.)

“The Company spent that night in the great cavernous hall, huddled close together in a corner to escape the draught: there seemed to be a steady inflow of chill air through the eastern archway. All about them as they lay hung the darkness, hollow and immense, and they were oppressed by the loneliness and vastness of the dolven halls and endlessly branching stairs and passages. The wildest imaginings that dark rumour had ever suggested to the hobbits fell altogether short of the actual dread and wonder of Moria.”

—J. R. R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring

48.)

“They stooped over the dark water. At first they could see nothing. Then slowly they saw the forms of the encircling mountains mirrored in a profound blue, and the peaks were like plumes of white flame above them; beyond there was a space of sky. There like jewels sunk in the deep shone glinting stars, though sunlight was in the sky above. Of their own stooping forms no shadow could be seen.”

—J. R. R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring

49.)

“I gazed around, taking in the grass, a reddish-brown chicken pecking at the side of the driveway, some rusty farm machinery, the wooden trestle table beside the road and the six empty metal milk churns that sat upon it. I saw the Hempstocks’ red-brick farmhouse, crouched and comfortable like an animal at rest. I saw the spring flowers; the omnipresent white and yellow daisies, the golden dandelions and do-you-like-butter buttercups, and, late in the season, a lone bluebell in the shadows beneath the milk-churn table, still glistening with dew…”

—Neil Gaiman, Ocean at the End of the Lane

50.)

“Snow was falling in the San Saba when they crossed it and snow was falling on the Edwards Plateau and in the Balcones the limestone was white with snow and he sat watching out while the gray flakes flared over the windshield glass in the sweep of the wipers. A translucent slush had begun to form along the edge of the blacktop and there was ice on the bridge over the Pedernales. The green water sliding slowly away past the dark bankside trees. The mesquites by the road so thick with mistletoe they looked like liveoaks. The driver sat hunched up over the wheel whistling silently to himself. “

—Cormac McCarthy, All the Pretty Horses

51.)

“They went on. Twice in the night they heard the little prairie vipers rattle among the scrub and they were afraid. With the dawn they were climbing among shale and whinstone under the wall of a dark monocline where turrets stood like basalt prophets and they passed by the side of the road little wooden crosses propped in cairns of stone where travelers had met with death. The road winding up among the hills and the castaways laboring upon the switchbacks, blackening under the sun, their eyeballs inflamed and the painted spectra racing out at the corners. Climbing up through ocotillo and pricklypear where the rocks trembled and sleared in the sun, rock and no water and the sandy trace and they kept watch for any green thing that might tell of water but there was no water. They ate pinole from a bag with their fingers and went on. Through the noon heat and into the dusk where lizards lay with their leather chins flat to the cooling rocks and fended off the world with thin smiles and eyes like cracked stone plates.

They crested the mountain at sunset and they could see for miles. An immense lake lay below them with the distant blue mountains standing in the windless span of water and the shape of a soaring hawk and trees that shimmered in the heat and a distant city very white against the blue and shaded hills. They sat and watched. They saw the sun drop under the jagged rim of the earth to the west and they saw it flare behind the mountains and they saw the face of the lake darken and the shape of the city dissolve upon it. They slept among the rocks face up like dead men and in the morning when they rose there was no city and no trees and no lake only a barren dusty plain.”

—Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian

52.)

“The beach was yellow sand, but at the water's edge a rubble of shell and algae took its place. Fiddler crabs bubbled and sputtered in their holes in the sand, and in the shallows little lobsters popped in and out of their tiny homes in the rubble and sand. The sea bottom was rich with crawling and swimming and growing things. The brown algae waved in the gentle currents and the green eel grass swayed and little sea horses clung to its stems. Spotted botete, the poison fish, lay on the bottom in the eel-grass beds, and the bright-coloured swimming crabs scampered over them.

On the beach the hungry dogs and the hungry pigs of the town searched endlessly for any dead fish or sea bird that might have floated in on a rising tide.

Although the morning was young, the hazy mirage was up. The uncertain air that magnified some things and blotted out others hung over the whole Gulf so that all sights were unreal and vision could not be trusted; so that sea and land had the sharp clarities and the vagueness of a dream. Thus it might be that the people of the Gulf trust things of the spirit and things of the imagination, but they do not trust their eyes to show them distance or clear outline or any optical exactness. Across the estuary from the town one section of mangroves stood clear and telescopically defined, while another mangrove clump was a hazy black-green blob. Part of the far shore disappeared into a shimmer that looked like water. There was no certainty in seeing, no proof that what you saw was there or was not there. And the people of the Gulf expected all places were that way, and it was not strange to them. A copper haze hung over the water, and the hot morning sun beat on it and made it vibrate blindingly.”

—John Steinbeck, The Pearl

53.)

“‘There I found a seat of some yellow metal that I did not recognize, corroded in places with a kind of pinkish rust and half smothered in soft moss, the armrests cast and filed into the resemblance of griffins’ heads. I sat down on it, and I surveyed the broad view of our old world under the sunset of that long day. It was as sweet and fair a view as I have ever seen. The sun had already gone below the horizon and the west was flaming gold, touched with some horizontal bars of purple and crimson. Below was the valley of the Thames, in which the river lay like a band of burnished steel. I have already spoken of the great palaces dotted about among the variegated greenery, some in ruins and some still occupied. Here and there rose a white or silvery figure in the waste garden of the earth, here and there came the sharp vertical line of some cupola or obelisk. There were no hedges, no signs of proprietary rights, no evidences of agriculture; the whole earth had become a garden.”

—H. G. Wells, The Time Machine

54.)

“The horizon was near; it always was in the Rockies, where longer views of the world were inevitably cut off by uptilted plates of bedrock. The sky was a perfect early-morning blue, innocent of clouds. A carpet of green forest climbed the flank of the nearest mountain. There were perhaps seventy acres of open ground between the house and the edge of the forest—the snow-cover over it was a perfect and blazing white. It was impossible to tell if the land beneath was tilled earth or open meadow. The view of this open square was interrupted by only one building: a neat red barn. When she spoke of her livestock or when he saw her trudging grimly past his window, breaking her breath with the impervious prow of her face, he had imagined a ramshackle outbuilding like an illustration from a child’s book of ghost stories — rooftree bowed and sagging from years of snow-weight, windows blank and dusty, some broken and blocked with pieces of cardboard, long double doors perhaps off their tracks and swaying outward. This neat and tidy structure with its dark-red paint and neat cream-colored trim looked like the five-car garage of a well-to-do country squire masquerading as a barn. In front of it stood a Jeep Cherokee, maybe five years old but obviously well cared for. To one side stood a Fisher plow in a home-made wooden cradle. To attach the plow to the Jeep, she would only need to drive the Jeep carefully up to the cradle so that the hooks on the frame matched the catches on the plow, and throw the locking lever on the dashboard. The perfect vehicle for a woman who lived alone and had no neighbor she could call upon for help (except for those dirty-birdie Roydmans, of course, and Annie probably wouldn’t take a plate of pork chops from them if she was dying of starvation). The driveway was neatly plowed, a testament to the fact that she did indeed use the blade, but he could not see the road — the house cut off the view.”

—Stephen King, Misery

55.)

“Out of the mist, one hundred yards away, came Tyrannosaurus Rex.

"It," whispered Eckels. "It......”

"Sh!"

It came on great oiled, resilient, striding legs. It towered thirty feet above half of the trees, a great evil god, folding its delicate watchmaker's claws close to its oily reptilian chest. Each lower leg was a piston, a thousand pounds of white bone, sunk in thick ropes of muscle, sheathed over in a gleam of pebbled skin like the mail of a terrible warrior. Each thigh was a ton of meat, ivory, and steel mesh. And from the great breathing cage of the upper body those two delicate arms dangled out front, arms with hands which might pick up and examine men like toys, while the snake neck coiled. And the head itself, a ton of sculptured stone, lifted easily upon the sky. Its mouth gaped, exposing a fence of teeth like daggers. Its eyes rolled, ostrich eggs, empty of all expression save hunger. It closed its mouth in a death grin. It ran, its pelvic bones crushing aside trees and bushes, its taloned feet clawing damp earth, leaving prints six inches deep wherever it settled its weight.

It ran with a gliding ballet step, far too poised and balanced for its ten tons. It moved into a sunlit area warily, its beautifully reptilian hands feeling the air.”

—Ray Bradbury, A Sound of Thunder

56.)

“She took the dead fish out of the net and examined it. It was still soft, not stiff, and it flopped in her hand. I had never seen so many colours: it was silver, yes, but beneath the silver was blue and green and purple and each scale was tipped with black.”

—Neil Gaiman, Ocean at the End of the Lane

57.)

“The clangor of the swords had died away, the shouting of the slaughter was hushed; silence lay on the red-stained snow. The pale bleak sun that glittered so blindingly from the ice-fields and the snow-covered plains struck sheens of silver from rent corselet and broken blade, where the dead lay in heaps.”

—Robert E. Howard, Gods of the North

58.)

“Shadow turned, slowly, streaming images of himself as he moved, frozen moments, each him captured in a fraction of a second, every tiny movement lasting for an infinite period. The images that reached his mind made no sense: it was like seeing the world through the multifaceted jeweled eyes of a dragonfly, but each facet saw something completely different, and he was unable to combine the things he was seeing, or thought he was seeing, into a whole that made any sense.

He was looking at Mr. Nancy, an old black man with a pencil mustache, in his check sports jacket and his lemon-yellow gloves, riding a carousel lion as it rose and lowered, high in the air; and, at the same time, in the same place, he saw a jeweled spider as high as a horse, its eyes an emerald nebula, strutting, staring down at him; and simultaneously he was looking at an extraordinarily tall man with teak-colored skin and three sets of arms, wearing a flowing ostrich-feather headdress, his face painted with red stripes, riding an irritated golden lion, two of his six hands holding on tightly to the beast’s mane; and he was also seeing a young black boy, dressed in rags, his left foot all swollen and crawling with blackflies; and last of all, and behind all these things, Shadow was looking at a tiny brown spider, hiding under a withered ocher leaf.

Shadow saw all these things, and he knew they were the same thing.

…

Shadow saw a gray-haired old Eastern- European immigrant, with a shabby raincoat and one iron-colored tooth, true. But he also saw a squat black thing, darker than the darkness that surrounded them, its eyes two burning coals; and he saw a prince, with long flowing black hair and a long black mustache, blood on his hands and his face, riding, naked but for a bear skin over his shoulder, on a creature half-man, half-beast, his face and torso blue-tattooed with swirls and spirals.

…

Again, a moment of double vision: Shadow saw the old woman, her dark face pinched with age and disapproval, but behind her he saw something huge, a naked woman with skin as black as a new leather jacket, and lips and tongue the bright red of arterial blood. Around her neck were skulls, and her many hands held knives, and swords, and severed heads.”

—Neil Gaiman, American Gods

59.)

“Misty auburn clouds, so thin they might be only illusion, spread below the ship. They caught red as dusk fell. The thick air refracted six times more than Earth’s, so sunsets had a slow-motion grandeur, the full palette of pinks and crimsons and rouge-reds.”

—Gregory Benford, The Clear Blue Seas of Luna

60.)

“Out in the cornfield, Anthony walked between the tall, rustling rows of green stalks. He liked to smell the corn. The alive corn overhead, and the old dead corn underfoot. Rich Ohio earth, thick with weeds and brown, dry-rotting ears of corn, pressed between his bare toes with every step--he had made it rain last night so everything would smell and feel nice today.

He walked clear to the edge of the cornfield, and over to where a grove of shadowy green trees covered cool, moist, dark ground, and lots of leafy undergrowth, and jumbled moss-covered rocks, and a small spring that made a clear, clean pool. Here Anthony liked to rest and watch the birds and insects and small animals that rustled and scampered and chirped about. He liked to lie on the cool ground and look up through the moving greenness overhead, and watch the insects flit in the hazy soft sunbeams that stood like slanting, glowing bars between ground and treetops. Somehow, he liked the thoughts of the little creatures in this place better than the thoughts outside; and while the thoughts he picked up here weren't very strong or very clear, he could get enough out of them to know what the little creatures liked and wanted, and he spent a lot of time making the grove more like what they wanted it to be. The spring hadn't always been here; but one time he had found thirst in one small furry mind, and had brought subterranean water to the surface in a clear cold flow, and had watched blinking as the creature drank, feeling its pleasure. Later he had made the pool, when he found a small urge to swim.

He had made rocks and trees and hushes and caves, and sunlight here and shadows there, because he had felt in all the tiny minds around him the desire--or the instinctive want--for this kind of resting place, and that kind of mating place, and this kind of place to play, and that kind of home.”

—Jerome Bixby, It’s a Good Life

61.)

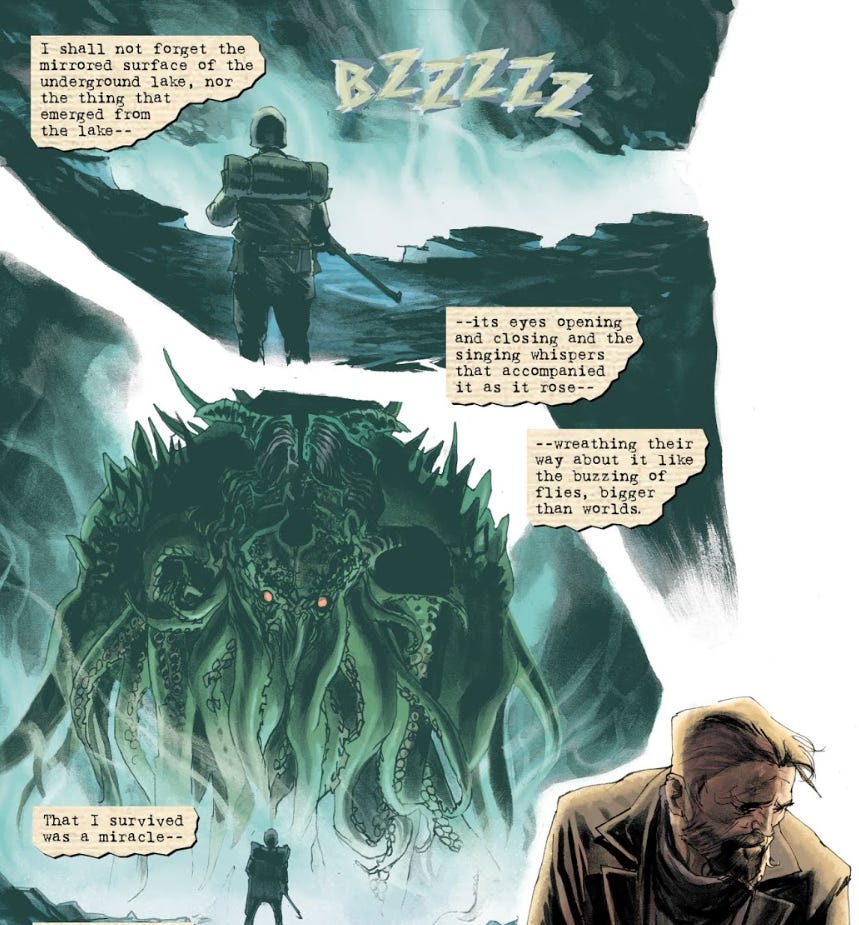

“I shall not forget the mirrored surface of the underground lake, nor the thing that emerged from the lake, its eyes opening and closing, and the singing whispers that accompanied it as it rose, wreathing their way about it like the buzzing of flies bigger than worlds.”

—Neil Gaiman, A Study in Emerald

62.)

“They were standing hand in hand in a snowy lane under a dark blue sky, in which the night’s first stars were already glimmering feebly. Cottages stood on either side of the narrow road, Christmas decorations twinkling in their windows. A short way ahead of them, a glow of golden streetlights indicated the center of the village.”

—J. K. Rowling, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows

63.)

“The following sunrise was something to behold. There was a rare break in the low dark clouds that allowed visible rays of golden smoke to slide sideways across the hills. Juliette lay in her cot, watching the dimness fade to light, her cheek resting on her hands, the smell of cold untouched oatmeal drifting from outside the bars.

…

As Juliette reached the top of the ramp, her head emerged into a lie, a grand and gorgeous untruth. Green grass covered the hills like newly laid carpet. The skies were intoxicatingly blue, the clouds bleached white like fancy linen, the air peppered with soaring things.”

—Hugh Howey, Wool Omnibus (retitled Silo)

64.)

“When he stopped much later the sun was hanging over the fields to his right, red and inflamed, and when he looked at his watch he saw that it was quarter past seven. The sun had stained the corntops a reddish gold, but here the shadows were dark and deep. He cocked his head, listening. With the coming of sunset the wind had died entirely and the corn stood still, exhaling its aroma of growth into the warm air.”

—Stephen King, Children of the Corn

Glad to see you back!