Q: Issac Simpson:

“What’s the quality of the stuff you’re getting for Passage Prize?”

A: Lomez:

“There’s huge variance here. Any nascent subculture will feature a lot of naive art. Amateurish art. It’s not polished or produced. It’s got a lot of energy, and this powerful creative force that compensates for the lack of craftsmanship or polish.

The people writing and submitting for us lack experience, they haven’t put in the hours into their craft necessary to generate work that’s high-quality craftsmanship.

On the other hand, we are getting some writing from people who I don’t know who they are, many of them are anons, but I can pretty easily tell they are accomplished, seasoned writers and artists. Because you can tell, there’s a certain polish there, the mechanics of the writing, if you know what they’re looking for, are all there.

You’re a writer, so I know you know this.

There’s these little hinge points in an essay or story where the writer is moving from one idea, or character viewpoint, to another, and it’s something that if you’re not practiced at it, it’s really easy to mess up, and it’s glaring. These little things you can get wrong.

So what we’re seeing is people who know how to do that. And I know these people are seasoned writers.”

—Lomez

47. Lomez - by Isaac Simpson - The Carousel (substack.com)

“The one consistent problem I see in most writing students’ work is plotting or pacing. Sometimes too fast, but more often too slow. This year I’ll focus on methods you might consider for keeping time and characters in motion throughout your work. In the real world, time has the nasty habit of passing. In the fictional world... time needs some help.”

—Chuck Palahniuk, 36 Craft Essays: Killing Time – Part One

“We read books where lifetimes pass in a paragraph, and in which civilizations rise and fall in the space of a single chapter. All of that human experience gets compressed under the weight of time, like geological strata that thin down centuries into millimetres of dirt: all of the boring bits, the long stretches of ordinary, day-to-day life, get tossed out, leaving only the significant events, resulting in the illusory sense that the significant events are all that there was. Our own memories work the same way: if we’re bored for an hour, or a year, time seems to stretch endlessly while we’re trapped in that boredom, but once it’s over our minds simply discard it, and it’s as though it never happened.”

—John Carter, Postcards from Barsoom: Nothing Ever Happens

Nothing Ever Happens - by John Carter (substack.com)

https://barsoom.substack.com/p/nothing-ever-happens

Time, and Time Again:

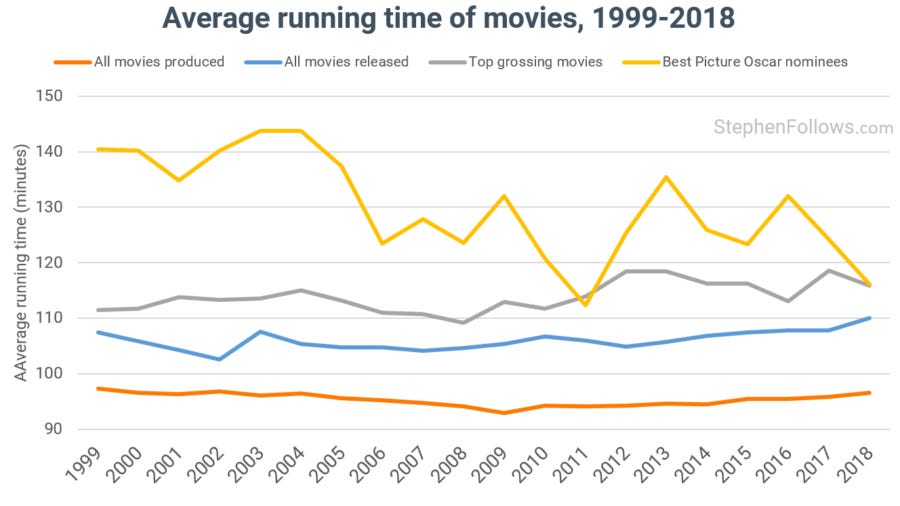

Compare the duration of films.

Today, the average movie hovers around 100 minutes. Short films are compressed close to 90 minutes; epic cinema stretches out to 120 minutes.

Rare blockbusters like Gone with the Wind, Ben-Hur, The Godfather Part II, Avatar 2, Avengers: Endgame, and LOTR: Return of the King can exceed three hours.

A dense mathematical formula has been applied. Commerce outweighs art. Audiences need time to watch a slate of unrelated movie trailers, prior to the movie. This pads the theatrical exhibit by twenty minutes, advertising future promotions. In-person chains of movie theaters prefer short, popular films… by reducing the length of movies, a fully-booked auditorium can theoretically be emptied and filled by another two, or three crowds per day. Total capacity can (theoretically) accommodate several hundred extra customers.

All of this is very boring, and there is no room for creativity or deviation. Profit margins have been graphed out to the last decimal point.

Mature industries settle into a stable mold… a Nash Equilibrium.

But the stories themselves diverge in scope, and scale, and ambition.

Action films depict blazing gunfights, besieged fortresses, reckless car chases which remain fused to the adrenaline and euphoria of living dangerously. Films like John Wick, Home Alone, Drive, Enemy of the State, The Terminator, World War Z, Mission Impossible, Taken, Sicario, Jurassic Park, National Treasure, True Lies, and Independence Day can tell a meaningful story which covers only a few weeks… days… or hours in terms of the narrative.

Poignant themes, and fascinating character arcs, can fit into that narrow schedule.

High-octane psychological thrillers.

Explosive dramatic momentum, paired with philosophical depth.

Die Hard shows the end of a marriage; a turbulent hostage situation; a brutal rescue; and the romantic catharsis of a bitter, career-oriented feminist falling back in love with the blue-collar, low-status, dangerous cop she married — an intense emotional transformation, which occurs on Christmas Eve within less than 24 hours.

The television show “24” is arranged around a very conscious manipulation of real-time. There are 24 episodes per season: each minute and second of screentime aligns with one corresponding minute, one corresponding second of narrative events. Each television season occurs within the terrifying, exuberant events of a single traumatic day.

In similar fashion, but brightened by a more playful and comedic tone, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off explores the goofy, forbidden shenanigans of a trio of high school friends who decide to skip school. They evade bureaucratic detection, travel Chicago, and say goodbye to the twilight of their shared childhood. And at the end of the movie, a rich boy who is terrified of his stern, overbearing father accidentally destroys his father’s most prized possession — a gleaming vintage Ferrari. As a result, the terrified rich boy must learn for the first time in his life to be brave, to be his own man, to stand up to his father… while accepting accountability for destroying something beautiful, irreplaceable, and expensive.

That juvenile comedy masks some heavy truths about life, family, regret, authority, duty, and the bittersweet pain of growing up.

Childhood ends; all men die; our lives measure up to a limited handful of moments, choices, betrayals, sacrifices.

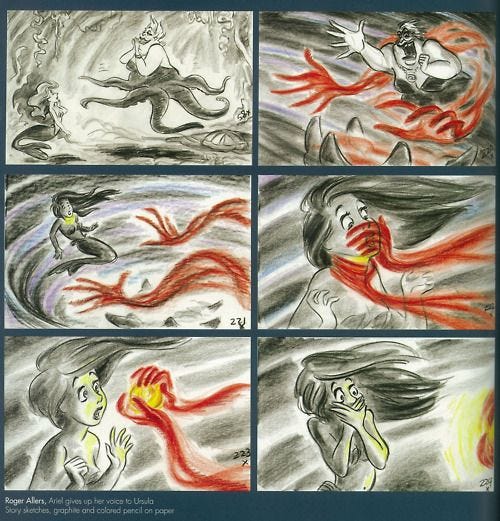

Contrast these action films, and comedy films, which occur in a single day — against the vast civilizational, historical panorama presented by a movie like 2001: A Space Odyssey. Stanley Kurbrik’s famous sci-fi mystery is an epic film which begins with monkeys battling before the birth of mankind… and it progresses into the distant future, where astronauts travel among the stars with spaceships, futuristic mechanisms, and Artificial Intelligence.

A two-hour film can cover a single important event. Or the birth, and death of a universe.

That’s a question of pacing.

Compare the word-count of novels.

Compare the panels, and layout of comic books.

The same question recurs.

Stories are tapestries, tapestries which paint with characters, characters who can build and destroy civilizations, civilizations which prosper or descend into tragedies, tragedies that communicate eternal lessons encoded as stories.

This is a key decision, to determine narrative scope.

How a story is framed affects every subsequent decision. That initial choice flows downhill, and creates a convoluted ecosystem of secondary consequences.

Time, and the curation of time, the presentation of time, the omission of insignificant details… these are crucial elements. Implicit aesthetic choices.

Framing a story efficiently is an underrated skill. Something which often goes unnoticed. And as a result, many books, comics, movies, and television serials are bogged down by unimportant content, slowed and bored by filler scenes which lack any kind of dramatic purpose.

Even many, perhaps most professionals don’t know how to think dramatically.

What this means is that scenes should be written less according to chronological sequence, and more appropriately to narrative significance. Dialogue can be structured so that exposition, tension, and emotions flow together in a gradual crescendo.

Details are arranged based on the emotional effect they will have upon characters — and the real-world audience.

Every character, scene, and detail needs to provide some kind of aesthetic functionality.

Pacing depends upon two related, overlapping skills:

Framing, and transitions.

Scale determines the size of the narrative: How many characters are involved? How many years does this story cover? What is the skeleton, the throughline, the connective tissue which connects all the disconnected ideas together into a coherent gestalt… in other words, what character arcs and plot lines and transformative payoffs will occur between Point A and Point B?

The velocity of the story is determined by the distance (duration of events from beginning to end), and speed (number of scenes, arrangement of events, digression of subplots, economy of detail) needed to travel from the hero’s origin to his eventual destiny.

Transitions skip, and blink, and glide, and hurry, and march, and stumble between these various separate concepts.

A good transition should be efficient. It should be elegant. It should be fast. It should be subtle. Most of all, a good transition should disguise the artificial nature of the artistic illusion so convincingly… so persuasively… so confidently that two completely unrelated, incompatible, perhaps even adversarial ideas, places, themes, or characters feel like they are part of the same shared world.

Amateur writers often struggle with transitions.

Connecting one cool idea to another delightful, unrelated concept is part of the daily process of storytelling. After a while, gliding between topics can become automatic. But the negative space between Point A and Point B, the absence of any substance, challenges beginners.

Some lessons can only be learned from experience. Questions of pacing, and the length of scenes, require practical answers.

There are a lot of tricks, we can explore a lot of potential answers, and we can read dozens of books which discuss these problems. On some level all of these tricks will be true, and correct, and stylish, and intelligent — and useless.

Too much education dulls the mind, blurs the senses, drowns the kernel of creative inspiration which is the engine of any great creative work.

Knowledge is useful, but knowledge must be paired with action, action which experiments and fails and then regroups to iterate.

The one trick I would say is: Learn to think visually.

Close your eyes. Dream in colors, and shapes.

Picture the characters in your mind. Picture their world. Then play with that image — imagine your hero consumed by flames. Or coated in oils and perfumed silks. Or armored by ugly, corrugated steel. Or encircled by slavering, ravenous, disease-tainted wolves. Or seated on a golden throne, flanked by hulking bodyguards, surrounded by seas of beautiful, half-naked harems.

This hero has very quickly changed identities — perhaps a martyr burnt alive for refusing to renounce his religion… then a pampered feudal aristocrat… then a brutal, belligerent conqueror… then a grim, battle-hardened soldier isolated in the wilderness… and finally a king beloved by a decadent, imperial citizenry.

Learn to think visually.

Take that image, transform it. Watch your hero gaining muscle, or deforming into a monster, or drowning beneath the ocean. Do the same thing to their environment.

Learn to think visually.

Build a city in your mind; tall, proud spires stabbing up into a soft blue sky, silver-gray clouds drifting slowly against the horizon. Populate your city with flying cars… or dinosaurs in business suits… or parasitic plants which mount humans and speak through their mouths like puppets. Send a comet to destroy that city. Watch smoke rising from the ruins. Then observe as spores find traction, and flowers bloom from the ruins of a once-proud metropolis.

Learn to think visually… play with the images, and then write what you see.

Character transformations can be marked by costume changes.

Study the costume changes of Star Wars, how each outfit communicates the psychology of a hero or villain. You can pick up a Star Wars toy from one of the first six movies, a children’s action figure, and their clothes will indicate what’s happening to them.

When you think visually, a lot of these storytelling problems naturally solve themselves. There is a clear image, guided by its own surreal, dreamlike logic — sort of a finished puzzle, waiting to be deciphered. And after you dream up a picture in your mind, the frustrating labor of writing is not quite so tedious… you are less “inventing” fiction than “describing” a vision which has already appeared to you.

Every movie, novel, and comic involves these aesthetic questions — the scale of a narrative, and the effort of moving from one idea to another. The real world results tend to be bland, and unimpressive. Most of their applied solutions are suboptimal, based on imitation of popular convention — and a blind, automatic inheritance of whatever patterns seem to form the default, shared consensus of a culture. Sometimes imitation leads to brilliant solutions, without any understanding of how, and why, a particular solution operates.

Framing, and transitions, offer some delightful aesthetic possibilities.

Along with inherent challenges.

Design problems.

There is never a perfect design. Design architecture always involves tradeoffs, the subtle art of hiding weaknesses, and emphasizing prominent strengths.

Below is a compilation of various examples of how to move between scenes, juggle time, and paint a vast panorama:

1.)

“Winter was waltzing closer and closer, whipping fierce winds and stabbing, frozen rains like shrapnel across the landscape.”

—T. R. Hudson, Automaton

Amazon.com: Automaton eBook : Hudson, T.R. : Kindle Store

2.)

“As they entered November, the weather turned very cold. The mountains around the school became icy grey and the lake like chilled steel. Every morning the ground was covered in frost.”

—J. K. Rowling, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone

3.)

“Dark came fast in the deep woods.”

—Stephen King, Rat

4.)

“While they had been talking, the train had carried them out of London. Now they were speeding past fields full of cows and sheep. They were quiet for a time, watching the fields and lanes flick past.”

—J. K. Rowling, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone

5.)

“The days wore on, with battles every day, until at last Ender settled into the routine of the destruction of himself.”

—Orson Scott Card, Ender’s Game

6.)

“There were no days in the unending stream of hours that followed. There were only ragged periods of sleep, apart at first, later together, as they held each other in free-fall. The sexual feel of skin and body became an anchor to their common humanity, a divided, frayed humanity so many light-years away that the concept no longer had any meaning. Life in the warm and swarming tunnels was the here and now; the two of them were like germs in a bloodstream, moving ceaselessly with the pulsing ebb and flow. Hours stretched into months, and time itself grew meaningless.”

—Bruce Sterling, Swarm

7.)

“Four hours later he was back in bed and he would have burned all his books for even a single Novril. Sitting hadn’t bothered him a bit while he was doing it — not with enough shit in his bloodstream to have put half the Prussian Army to sleep — but now it felt as if a swarm of bees had been loosed in the lower half of his body.”

—Stephen King, Misery

8.)

“At first, finding himself alone in Chiba, with little money and less hope of finding a cure, he’d gone into a kind of terminal overdrive, hustling fresh capital with a cold intensity that had seemed to belong to someone else. In the first month, he’d killed two men and a woman over sums that a year before would have seemed ludicrous. Ninsei wore him down until the street itself came to seem the externalization of some death wish, some secret poison he hadn’t known he carried.”

—William Gibson, Neuromancer

9.)

“Gurgeh found the days slipping by almost unnoticed. He would sleep only two or three hours each night, and the rest of the time he was in front of the screen, or sometimes standing in the middle of one of the game-boards as the ship talked to him, drew holo diagrams in the air, and moved pieces about. He was glanding the whole time, his bloodstream full of secreted drugs, his brain pickled in their genofixed chemistry as his much-worked maingland - five times the human-basic size it had been in his primitive ancestors - pumped, or instructed other glands to pump, the coded chemicals into his body.”

—Iain M. Banks, Player of Games

10.)

“Just before it was dark, as they passed a great island of Sargasso weed that heaved and swung in the light sea as though the ocean were making love with something under a yellow blanket, his small line was taken by a dolphin. He saw it first when it jumped in the air, true gold in the last of the sun and bending and flapping wildly in the air. It jumped again and again in the acrobatics of its fear and he worked his way back to the stern and crouching and holding the big line with his right hand and arm, he pulled the dolphin in with his left hand, stepping on the gained line each time with his bare left foot. When the fish was at the stem, plunging and cutting from side to side in desperation, the old man leaned over the stern and lifted the burnished gold fish with its purple spots over the stem.”

—Ernest Hemingway, The Old Man and the Sea

11.)

“It was colder. Nothing moved in that high world. A rich smell of woodsmoke hung over the road. He pushed the cart on through the snow. A few miles each day. He'd no notion how far the summit might be. They ate sparely and they were hungry all the time. He stood looking out over the country. A river far below. How far had they come?”

—Cormac McCarthy, The Road

12.)

“An hour later he was sitting on a rock at the edge of the two-lane, waiting for a seemingly endless freight train to cross the road.”

—Stephen King, The Institute

13.)

Every year, after the lottery, Mr. Summers began talking about a new box, but every year the subject was allowed to fade off without anything being done. The black box grew shabbier each year; by now it was no longer completely black but splintered badly along one side to show the original wood color, and in some places faded or stained.”

—Shirley Jackson, The Lottery

14.)

“He fit in well now. With his corpses.

Yet — not completely. Inside, the dream. Something believed, something hungered, something yearned. It was strong enough to keep him away from the meathouse, from the vegetable life the others had all chosen. And sometimes, on bleak lonely nights, it would grow stronger still.

Then Trager would rise from his empty bed, dress, and walk the corridors for hours with his hands shoved deep into his pockets while something twisted, clawed and whimpered in his gut. Always, before his walks were over, he would resolve to do something, to change his life tomorrow. But when tomorrow came, the silent gray corridors were half forgotten, the demons had faded, and he had six roaring, shaking automills to drive across the pit. He would lose himself in routine, and it would be long months before the feelings came again.”

—George R. R. Martin, Meathouse Man

15.)

“Ned closed his eyes and opened them; it made no difference. He slept and woke and slept again. He did not know which was more painful, the waking or the sleeping. When he slept, he dreamed: dark disturbing dreams of blood and broken promises. When he woke, there was nothing to do but think, and his waking thoughts were worse than nightmares.”

—George R. R. Martin, A Game of Thrones

16.)

“They drank until closing, him and Mueller and the Andersons, who came in later, and others, friends and enemies and people that Sykes had long ago forgotten. Then they went to Kenyon’s apartment behind the tavern and drank some more, and big mouth Mueller laughed uproariously and told stories about the old days and dirty jokes about his corpses and asked Sykes what the tail was like on Vendalia and Skrakky. Then, finally, Mueller passed out and the others left and Sykes got some sleep.

But he was up before dawn.”

—George R. R. Martin, Nobody Leaves New Pittsburgh

17.)

“When night finally fell the stars burned shrilly overhead with impossible force and beauty. Quentin jogged with his head up, knees high, no longer feeling anything below his waist, gloriously isolated, lost in the spectacle. He became nothing, a running wraith, a wisp of warm flesh in a silent universe of midnight frost.”

—Lev Grossman, The Magicians

18.)

“The arguing raged on late into the night. Each lord had a right to speak, and speak they did… and shout, and curse, and reason, and cajole, and jest, and bargain, and slam tankards on the table, and threaten, and walk out, and return sullen or smiling. Catelyn sat and listened to it all.”

—George R. R. Martin, A Game of Thrones

19.)

“He talked for a long time, and the longer he talked, the more horrified she became. All these years she’d been living with a madman, but how could she have known? His insanity was like an underground sea. There was a layer of rock over it, and a layer of soil over the rock; flowers grew there. You could stroll through them and never know the madwater was there, but it was. It always had been.

—Stephen King, A Good Marriage

20.)

“So they sat there in the shade where the camp was pitched under some wide-topped acacia trees with a boulder-strewn cliff behind them, and a stretch of grass that ran to the bank of a boulder-filled stream in front with forest beyond it, and drank their just-cool lime drinks and avoided one another’s eyes while the boys set the table for lunch. Wilson could tell that the boys all knew about it now and when he saw Macomber’s personal boy looking curiously at his master while he was putting dishes on the table he snapped at him in Swahili. The boy turned away with his face blank.”

—Ernest Hemingway, The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber

21.)

“Standing outside, Roland had judged the Tower to be roughly six hundred feet high. But as he peered into the hundredth room, and then the two hundredth, he felt sure he must have climbed eight times six hundred. Soon he would be closing in on the mark of distance his friends from America-side had called a mile. That was more floors than there possibly could be — no Tower could be a mile high! — but still he climbed, climbed until he was nearly running, yet never did he tire. It once crossed his mind that he’d never reach the top; that the Dark Tower was infinite in height as it was eternal in time. But after a moment’s consideration he rejected the idea, for it was his life the Tower was telling, and while that life had been long, it had by no means been eternal. And as it had had a beginning (marked by the cedar clip and the bit of blue silk ribbon), so it would have an ending.

Soon now, quite likely.”

—Stephen King, The Dark Tower

22.)

“In the days that followed, as Dawson grew closer and closer, Buck still continued to interfere between Spitz and the culprits; but he did it craftily, when Francois was not around, With the covert mutiny of Buck, a general insubordination sprang up and increased. Dave and Sol-leks were unaffected, but the rest of the team went from bad to worse. Things no longer went right. There was continual bickering and jangling. Trouble was always afoot, and at the bottom of it was Buck. He kept Francois busy, for the dog-driver was in constant apprehension of the life-and-death struggle between the two which he knew must take place sooner or later; and on more than one night the sounds of quarreling and strife among the other dogs turned him out of his sleeping robe, fearful that Buck and Spitz were at it.

But the opportunity did not present itself, and they pulled into Dawson one dreary afternoon with the great fight still to come. Here were many men, and countless dogs, and Buck found them all at work.”

—Jack London, Call of the Wild

23.)

“Summer arrived, and dogs and men packed on their backs, rafted across blue mountain lakes, and descended or ascended unknown rivers in slender boats whipsawed from the standing forest.

The months came and went, and back and forth they twisted through the uncharted vastness, where no men were and yet where men had been if the Lost Cabin were true. They went across divides in summer blizzards, shivered under the midnight sun on naked mountains between the timber line and the eternal snows, dropped into summer valleys amid swarming gnats and flies, and in the shadows of glaciers picked strawberries and flowers as ripe and fair as any the Southland could boast.

In the fall of the year they penetrated a weird lake country, sad and silent, where wild-fowl had been, but where then there was no life nor sign of life—only the blowing of chill winds, the forming of ice in sheltered places, and the melancholy rippling of waves on lonely beaches.

And through another winter they wandered on the obliterated trails of men who had gone before.”

—Jack London, Call of the Wild

24.)

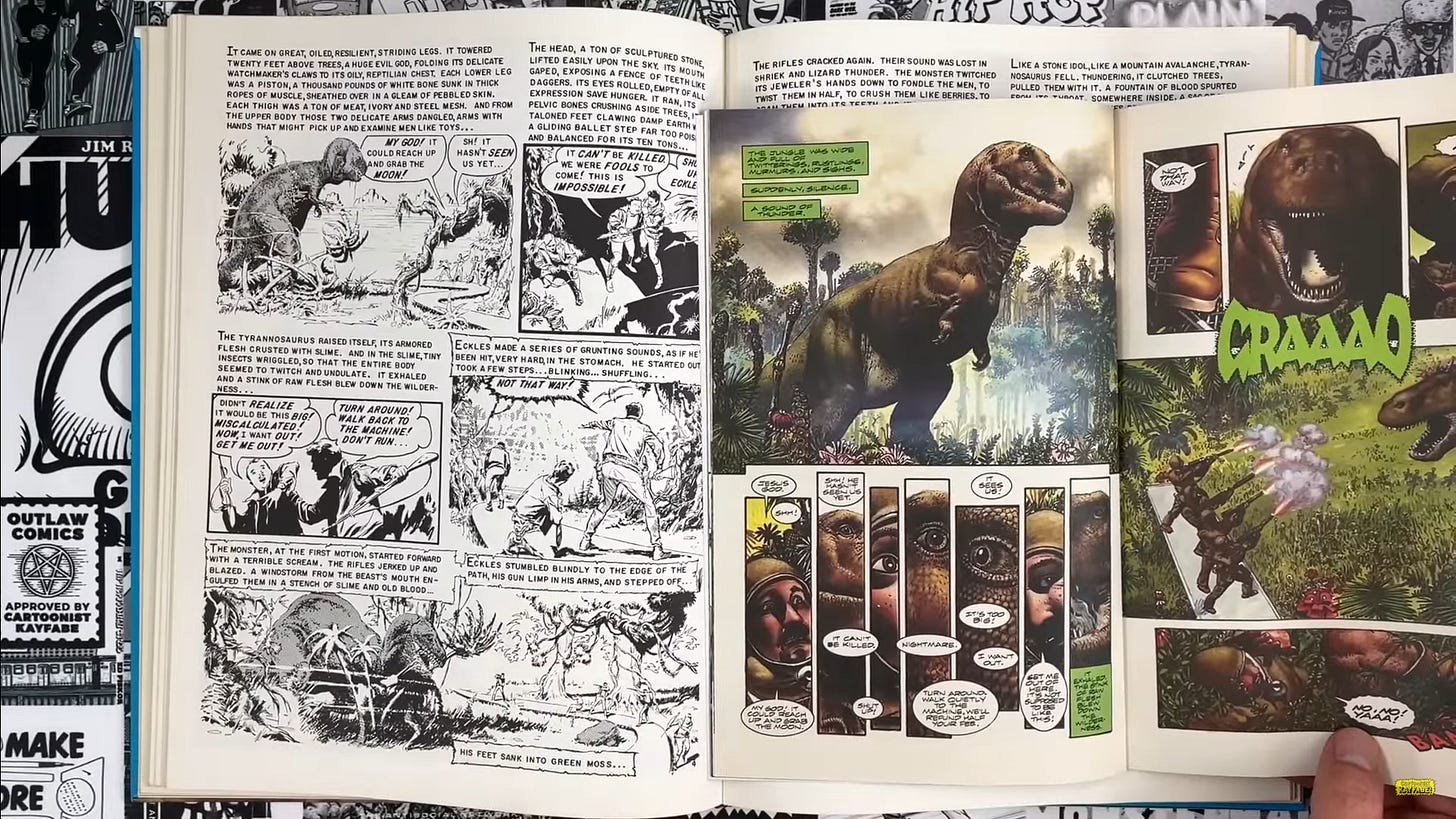

“They moved silently across the room, taking their guns with them, toward the Machine, toward the silver metal and the roaring light.

First a day and then a night and then a day and then a night, then it was day-night-day-night. A week, a month, a year, a decade! A.D. 2055. A.D. 2019. 1999! 1957! Gone! The Machine roared.

They put on their oxygen helmets and tested the intercoms. Eckels swayed on the padded seat, his face pale, his jaw stiff. He felt the trembling in his arms and he looked down and found his hands tight on the new rifle. There were four other men in the Machine. Travis, the Safari Leader, his assistant, Lesperance, and two other hunters, Billings and Kramer. They sat looking at each other, and the years blazed around them.

…

The Machine howled. Time was a film run backward. Suns fled and ten million moons fled after them. "Think," said Eckels. "Every hunter that ever lived would envy us today. This makes Africa seem like Illinois."

The Machine slowed; its scream fell to a murmur. The Machine stopped.

The sun stopped in the sky.”

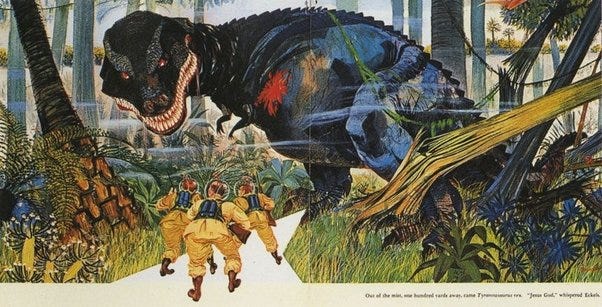

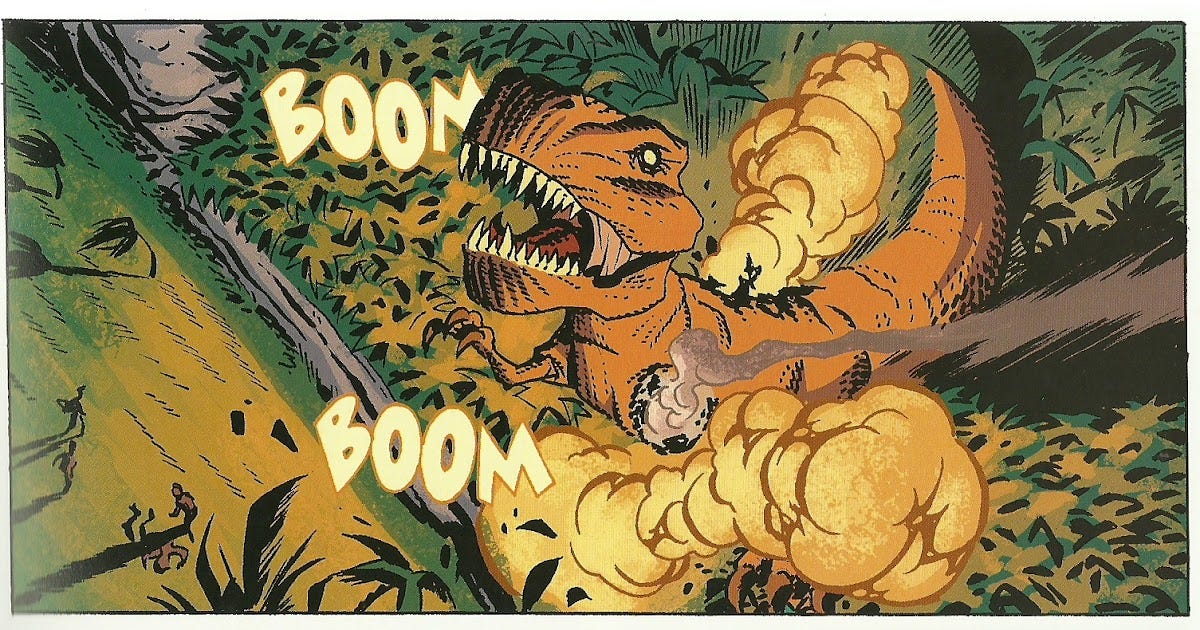

—Ray Bradbury, A Sound of Thunder

25.)

“He had been appointed to a sub-committee of a sub-committee which had sprouted from one of the innumerable committees dealing with minor difficulties that arose in the compilation of the Eleventh Edition of the Newspeak Dictionary. They were engaged in producing something called an Interim Report, but what it was that they were reporting on he had never definitely found out. It was something to do with the question of whether commas should be placed inside brackets, or outside. There were four others on the committee, all of them persons similar to himself. There were days when they assembled and then promptly dispersed again, frankly admitting to one another that there was not really anything to be done. But there were other days when they settled down to their work almost eagerly, making a tremendous show of entering up their minutes and drafting long memoranda which were never finished — when the argument as to what they were supposedly arguing about grew extraordinarily involved and abstruse, with subtle haggling over definitions, enormous digressions, quarrels — threats, even, to appeal to higher authority. And then suddenly the life would go out of them and they would sit round the table looking at one another with extinct eyes, like ghosts fading at cock-crow.”

—George Orwell, 1984

26.)

“At five A.M. the alarm clock exploded on the new bed table under the new lamp, and was immediately silenced. Mitch staggered through the dark house and found Hearsay waiting at the back door. He released him into the backyard and headed for the shower. Twenty minutes later he found his wife under the covers and kissed her goodbye. She did not respond.

With no traffic to fight, the office was ten minutes away. He had decided his day would start at five-thirty, unless someone could top that; then he would be there at five, or fourthirty, or whenever it took to be first. Sleep was a nuisance. He would be the first lawyer to arrive at the Bendini Building on this day, and every day until he became a partner. If it took the others ten years, he could do it in seven. He would become the youngest partner in the history of The Firm, he had decided.”

—John Grisham, The Firm

27.)

“There were questions asked and answers given there in the chill of morning, but afterward Bran could not recall much of what had been said. Finally, his lord father gave a command, and two of his guardsmen dragged the ragged man to the ironwood stump in the center of the square. They forced his head down onto the hard black wood.

…

Bran kept his pony well in hand, and did not look away.

His father took off the man’s head with a single sure stroke. Blood sprayed out across the snow, as red as summerwine. One of the horses reared and had to be restrained to keep from bolting. Bran could not take his eyes off the blood. The snows around the stump drank it eagerly, reddening as he watched.”

—George R. R. Martin, A Game of Thrones

28.)

“Best not to think on the past.

I’ve spent so very long in the ice already. I didn’t know how long until the world put the clues together, deciphered the notes and the tapes from the Norwegian camp, pinpointed the crash site. I was being Palmer, then; unsuspected, I went along for the ride.

I even allowed myself the smallest ration of hope.

But it wasn’t a ship any more. It wasn’t even a derelict. It was a fossil, embedded in the floor of a great pit blown from the glacier. Twenty of these skins could have stood one atop another, and barely reached the lip of that crater. The timescale settled down on me like the weight of a world: how long for all that ice to accumulate? How many eons had the universe iterated on without me?

And in all that time, a million years perhaps, there’d been no rescue. I never found myself. I wonder what that means. I wonder if I even exist any more, anywhere but here.”

—Peter Watts, The Things

The Things by Peter Watts : Clarkesworld Magazine – Science Fiction & Fantasy

29.)

“In a pool of the wizard’s blood, by the light of blazing torches, he caught sight of himself. He saw a huge and monstrous creature with an apelike face and tired, lost eyes.

Along with his mind he seemed to be losing even the form of a man, as the corrosive influence of his surroundings worked to transform him.

After that night, he tried to re-dedicate himself to Khorne, to lose himself in the wine of battle and drown out thoughts of his fading humanity in gore.

…

With each gift his humanity seemed to fade, his sick hopelessness to withdraw, to form a small solid kernel buried deep in his mind. Memories of his homeland, friends and family had all but gone, like old paintings whose pigment has faded to the point of invisibility. He became only dimly aware of the beings about him, seeing them only as victims or slaves.”

—William King, The Laughter of Dark Gods

30.)

“The intricacies of scrollwork and the excruciating delicacy of the gold inlay work would, because of the brevity of his spare-project time, make it a labor of many years; but in a dark sea of centuries wherein nothing seemed to flow, a lifetime was only brief eddy, even for the man who lived it. There was a tedium of repeated days and repeated seasons; then there were aches and pains, finally Extreme Unction, and a moment of blackness at the end — or at the beginning, rather. For then the small shivering soul who had endured the tedium, endured it badly or well, would find itself in a place of light, find itself absorbed in the burning gaze of infinitely compassionate eyes as it stood before the Just One.”

—Walter M. Miller Jr., A Canticle for Leibowitz

31.)

“Jeff went back to New York alone, back to his investments.

Skirts, he knew, would be getting shorter for the next few years, creating an enormous demand for patterned stockings and panty hose. Jeff bought thirty thousand shares of Hanes. All those exposed thighs had to lead somewhere; he bought heavily in the pharmaceutical houses that manufactured birth-control pills.

…

Fast-food chains—Jeff chose Denny’s, Kentucky Fried Chicken, and McDonald’s—went through a big slump in 1967, before skyrocketing up an average five hundred percent one year later.

By 1968 his company’s assets were into the hundreds of millions, and he had approved an I. M. Pei design for a sixty-story corporate-headquarters building at Park and Fifty-third. Jeff also mandated the purchase of extensive parcels of land in choice commercial and residential areas of Houston, Denver, Atlanta, and Los Angeles. The company bought close to half of the undeveloped property in L.A.’s new Century City project, at a price of five dollars per square foot. For his personal use, Jeff bought a three-hundred-acre estate in Dutchess County, two hours up the Hudson from Manhattan.

He went out with a variety of women, slept with some of them, hated the whole meaningless process.

Drinks, dinners, plays and concerts and gallery openings … He grew to despise the rigid formality of dating, missed the easy familiarity of simply being with someone, sharing friendly silences and unforced laughter. Besides, most of the women he met were either too openly interested in his wealth or too studiedly blasé about it. Some even hated him for it, refused to go out with him because of it… He bided his time, focused his energies on work.”

—Ken Grimwood, Replay

32.)

“There was a rhythm in my arms, my legs. With each pulse of blood, a kind of sound welled up within me, like an orchestra thousands strong, but not playing in unison; playing whole seasons of symphonies at once. Music in the blood. The sound became harsher, but more coordinated, wave-trains finally canceling into silence, then separating into harmonic beats.

The beats seemed to melt into me, into the sound of my own heart.

First, they subdued our immune responses. The war—and it was a war, on a scale never before known on Earth, with trillions of combatants—lasted perhaps two days.

By the time I regained enough strength to get to the kitchen faucet, I could feel them working on my brain, trying to crack the code and find the god within the protoplasm. I drank until I was sick, then drank more moderately and took a glass to Gail. She sipped at it. Her lips were cracked, her eyes bloodshot and ringed with yellowish crumbs. There was some color in her skin. Minutes later, we were eating feebly in the kitchen.

…

They had learned inside Vergil; their tactics within the two of us were very different. I itched all over for about two hours—two hours in hell—before they made the breakthrough and found me. The effort of ages on their timescale paid off and they communicated smoothly and directly with this great, clumsy intelligence who had once controlled their universe.

They were not cruel. When the concept of discomfort and its undesirability was made clear, they worked to alleviate it. They worked too effectively. For another hour, I was in a sea of bliss, out of all contact with them.

With dawn the next day, they gave us freedom to move again; specifically, to go to the bathroom.”

—Greg Bear, Blood Music

33.)

“At first it had not come easy. The khalasar had broken camp the morning after her wedding, moving east toward Vaes Dothrak, and by the third day Dany thought she was going to die. Saddle sores opened on her bottom, hideous and bloody. Her thighs were chafed raw, her hands blistered from the reins, the muscles of her legs and back so wracked with pain that she could scarcely sit. By the time dusk fell, her handmaids would need to help her down from her mount.

Even the nights brought no relief. Khal Drogo ignored her when they rode, even as he had ignored her during their wedding, and spent his evenings drinking with his warriors and bloodriders, racing his prize horses, watching women dance and men die. Dany had no place in these parts of his life. She was left to sup alone, or with Ser Jorah and her brother, and afterward to cry herself to sleep. Yet every night, some time before the dawn, Drogo would come to her tent and wake her in the dark, to ride her as relentlessly as he rode his stallion. He always took her from behind, Dothraki fashion, for which Dany was grateful; that way her lord husband could not see the tears that wet her face, and she could use her pillow to muffle her cries of pain. When he was done, he would close his eyes and begin to snore softly and Dany would lie beside him, her body bruised and sore, hurting too much for sleep.

Day followed day, and night followed night, until Dany knew she could not endure a moment longer. She would kill herself rather than go on, she decided one night …

Yet when she slept that night, she dreamt the dragon dream again. Viserys was not in it this time. There was only her and the dragon. Its scales were black as night, wet and slick with blood. Her blood, Dany sensed. Its eyes were pools of molten magma, and when it opened its mouth, the flame came roaring out in a hot jet. She could hear it singing to her. She opened her arms to the fire, embraced it, let it swallow her whole, let it cleanse her and temper her and scour her clean. She could feel her flesh sear and blacken and slough away, could feel her blood boil and turn to steam, and yet there was no pain. She felt strong and new and fierce.

And the next day, strangely, she did not seem to hurt quite so much.”

—George R. R. Martin, A Game of Thrones

34.)

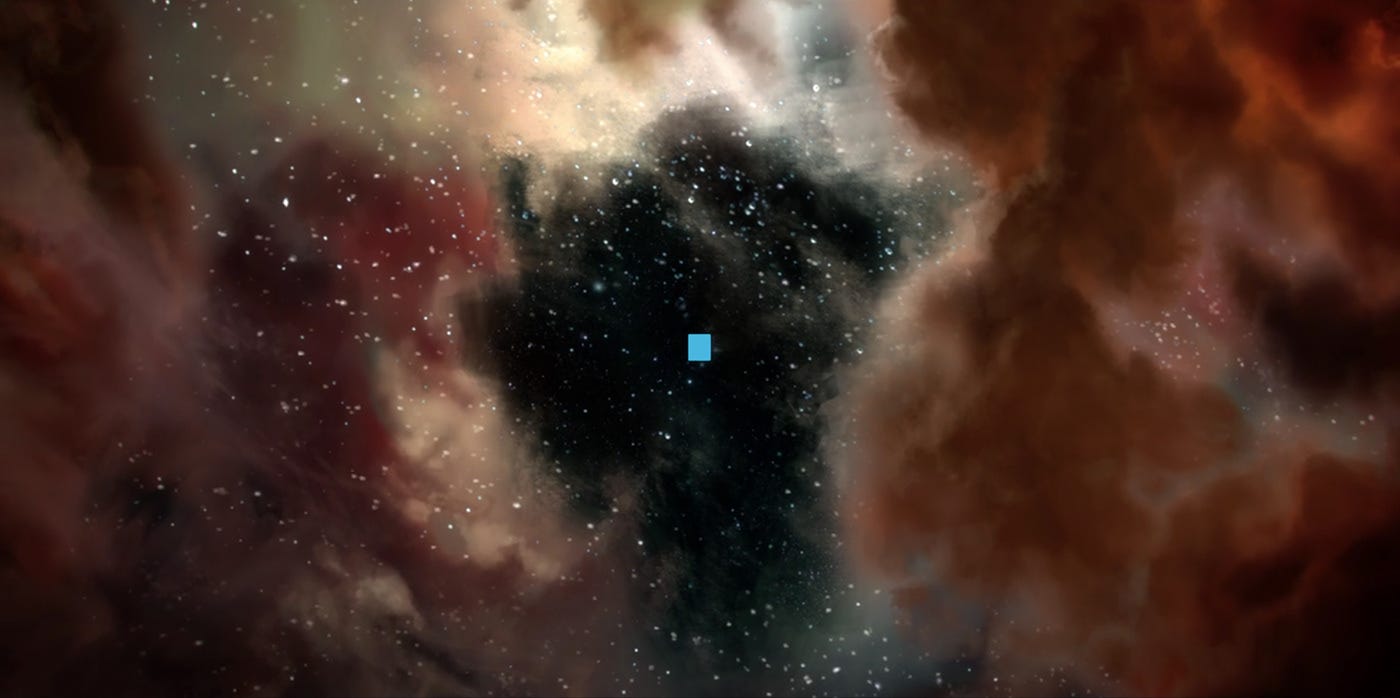

“One day — after a longer than usual gestation period — Zima unveiled a mural that had something different about it. It was a picture of a swirling, star-pocked nebula, from the vantage point of an airless rock. Perched on the rim of a crater in the middle distance, blocking off part of the nebula, was a tiny blue square. At first glance it looked as if the canvas had been washed blue and Zima had simply left a small area unpainted. There was no solidity to the square; no detail or suggestion of how it related to the landscape or the backdrop. It cast no shadow and had no tonal influence on the surrounding colours. But the square was deliberate: close examination showed that it had indeed been overpainted over the rocky lip of the crater. It meant something.

The square was just the beginning. Thereafter, every mural that Zima released to the outside world contained a similar geometric shape: a square, triangle, oblong or some similar form embedded somewhere in the composition. It was a long time before anyone noticed that the shade of blue was the same from picture to picture.

It was Zima Blue: the same shade of blue as on the gold-lettered card.

Over the next decade or so, the abstract shapes became more dominant, squeezing out the other elements of each composition. The cosmic vistas ended up as narrow borders, framing blank circles, triangles, rectangles. Where his earlier work had been characterised by exuberant brushwork and thick layers of paint, the blue forms were rendered with mirror-smoothness.”

—Alastair Reynolds, Zima Blue

35.)

“In the following year, one of the sisters would be fifteen: but as each was a year younger than the other, the youngest would have to wait five years before her turn came to rise up from the bottom of the ocean, and see the earth as we do. However, each promised to tell the others what she saw on her first visit, and what she thought the most beautiful; for their grandmother could not tell them enough; there were so many things on which they wanted information. None of them longed so much for her turn to come as the youngest, she who had the longest time to wait, and who was so quiet and thoughtful. Many nights she stood by the open window, looking up through the dark blue water, and watching the fish as they splashed about with their fins and tails. She could see the moon and stars shining faintly; but through the water they looked larger than they do to our eyes. When something like a black cloud passed between her and them, she knew that it was either a whale swimming over her head, or a ship full of human beings, who never imagined that a pretty little mermaid was standing beneath them, holding out her white hands towards the keel of their ship.

As soon as the eldest was fifteen, she was allowed to rise to the surface of the ocean. When she came back, she had hundreds of things to talk about; but the most beautiful, she said, was to lie in the moonlight, on a sandbank, in the quiet sea, near the coast, and to gaze on a large town nearby, where the lights were twinkling like hundreds of stars; to listen to the sounds of the music, the noise of carriages, and the voices of human beings, and then to hear the merry bells peal out from the church steeples; and because she could not go near to all those wonderful things, she longed for them more than ever. Oh, did not the youngest sister listen eagerly to all these descriptions? and afterwards, when she stood at the open window looking up through the dark blue water, she thought of the great city, with all its bustle and noise, and even fancied she could hear the sound of the church bells, down in the depths of the sea.

In another year the second sister received permission to rise to the surface of the water, and to swim about where she pleased. She rose just as the sun was setting, and this, she said, was the most beautiful sight of all. The whole sky looked like gold, while violet and rose-colored clouds, which she could not describe, floated over her; and, still more rapidly than the clouds, flew a large flock of wild swans towards the setting sun, looking like a long white veil across the sea. She also swam towards the sun; but it sunk into the waves, and the rosy tints faded from the clouds and from the sea.

The third sister's turn followed; she was the boldest of them all, and she swam up a broad river that emptied itself into the sea.

…

The fourth sister was more timid; she remained in the midst of the sea, but she said it was quite as beautiful there as nearer the land.

…

The fifth sister's birthday occurred in the winter; so when her turn came, she saw what the others had not seen the first time they went up. The sea looked quite green, and large icebergs were floating about, each like a pearl, she said, but larger and loftier than the churches built by men. They were of the most singular shapes, and glittered like diamonds.”

—Hans Christian Anderson, The Little Mermaid

36.)

“And saw her brother Rhaegar, mounted on a stallion as black as his armor. Fire glimmered red through the narrow eye slit of his helm. “The last dragon,” Ser Jorah’s voice whispered faintly. “The last, the last.” Dany lifted his polished black visor. The face within was her own.

After that, for a long time, there was only the pain, the fire within her, and the whisperings of stars.

She woke to the taste of ashes.”

—George R. R. Martin, A Game of Thrones

37.)

“When I brought myself to look at the dials again I was amazed to find where I had arrived. One dial records days, another thousands of days, another millions of days, and another thousands of millions. Now, instead of reversing the levers, I had pulled them over so as to go forward with them, and when I came to look at these indicators I found that the thousands hand was sweeping round as fast as the seconds hand of a watch — into futurity.

As I drove on, a peculiar change crept over the appearance of things. The palpitating greyness grew darker; then — though I was still travelling with prodigious velocity — the blinking succession of day and night, which was usually indicative of a slower pace, returned, and grew more and more marked. This puzzled me very much at first. The alternations of night and day grew slower and slower, and so did the passage of the sun across the sky, until they seemed to stretch through centuries. At last a steady twilight brooded over the earth, a twilight only broken now and then when a comet glared across the darkling sky. The band of light that had indicated the sun had long since disappeared; for the sun had ceased to set — it simply rose and fell in the west, and grew ever broader and more red. All trace of the moon had vanished. The circling of the stars, growing slower and slower, had given place to creeping points of light. At last, some time before I stopped, the sun, red and very large, halted motionless upon the horizon, a vast dome glowing with a dull heat, and now and then suffering a momentary extinction. At one time it had for a little while glowed more brilliantly again, but it speedily reverted to its sullen red heat. I perceived by this slowing down of its rising and setting that the work of the tidal drag was done. The earth had come to rest with one face to the sun, even as in our own time the moon faces the earth. Very cautiously, for I remembered my former headlong fall, I began to reverse my motion. Slower and slower went the circling hands until the thousands one seemed motionless and the daily one was no longer a mere mist upon its scale. Still slower, until the dim outlines of a desolate beach grew visible.

…

The machine was standing on a sloping beach.

…

‘I cannot convey the sense of abominable desolation that hung over the world. The red eastern sky, the northward blackness, the salt Dead Sea, the stony beach crawling with these foul, slow-stirring monsters, the uniform poisonous-looking green of the lichenous plants, the thin air that hurts one’s lungs; all contributed to an appalling effect. I moved on a hundred years, and there was the same red sun — a little larger, a little duller — the same dying sea, the same chill air, and the same crowd of earthy crustacea creeping in and out among the green weed and the red rocks. And in the westward sky I saw a curved pale line like a vast new moon.

So I travelled, stopping ever and again, in great strides of a thousand years or more, drawn on by the mystery of the earth’s fate, watching with a strange fascination the sun grow larger and duller in the westward sky, and the life of the old earth ebb away. At last, more than thirty million years hence, the huge red-hot dome of the sun had come to obscure nearly a tenth part of the darkling heavens. Then I stopped once more, for the crawling multitude of crabs had disappeared, and the red beach, save for its livid green liverworts and lichens, seemed lifeless. And now it was flecked with white. A bitter cold assailed me. Rare white flakes ever and again came eddying down. To the north-eastward, the glare of snow lay under the starlight of the sable sky, and I could see an undulating crest of hillocks pinkish white. There were fringes of ice along the sea margin, with drifting masses further out; but the main expanse of that salt ocean, all bloody under the eternal sunset, was still unfrozen.

I looked about me to see if any traces of animal life remained. A certain indefinable apprehension still kept me in the saddle of the machine. But I saw nothing moving, in earth or sky or sea. The green slime on the rocks alone testified that life was not extinct.”

—H. G. Wells, The Time Machine

Excellent piece!

Have you by chance read “The Woman Chaser” by Charles Willeford? You brought it to mind for me in two ways. First because I admire the way he handles time and transitions in the story. And second because near the end, the main character gets into a violent struggle about how long his movie should run. The producers have proposed dismembering his work in two different ways, either expanding it into a meaningless television series and discarding the movie distribution, or cutting the movie so severely as to demolish the story.

Dear Billionaire Psycho (BP), I have been binge reading all your articles since I found the link to Pygmalion and the Anime Girl in The American Sun, which I have been reading since 2019.

I appreciate your articles about storytelling since I want to make my own stories as well in visual formats about adult protagonists, globe-trotting adventures and bloody fights (things that appeal to men since time immemorial).

That being said having characters from different parts of our world is a sensible topic as I hesitate to consider some groups that I am biased against, especially concerning groups that I don't have positive views such as Africans, Arabs, South Asians and the Chinese. I have worries whether making a character of any of these 4 as benevolent will make the story as subversive as Big Hollywood productions are since the evidence against them is high.

I will keep in touch with your future articles nevertheless.

Stay Psycho