Dean Koontz:

“The English language is so rich, that when you allow yourself not only to be flat discussion of action, and character and moving the story forward, and you don’t use all the tools in the toolbox, you’re just leaving something out. I love to use a moment of description, I don’t go on for six pages describing a room, but you find those images that stick in the reader’s mind.

When I describe that sky, or the landscape with the snow, it needs to serve three functions.

One of them is Mood. It really needs to serve the mood of the scene. Number two is, it needs to be saying something — no matter how subtle — about character, or the character’s state of mind. Because every scene is written from the point of view of one character. Everything that’s said, or you see in that scene, even if it’s not first person, it’s coming through that character’s perspective. So when Jane is seeing that sky, and thinking of it that way, her viewpoint on the landscape’s emotion is describing Jane’s mood.

So, mood of the scene, mood of the character, and there’s many other purposes it can serve, and one of them is theme. If you’re dealing with a novel about the existence (or not) of free will, and the existence of freedom, what it takes to sustain freedom, then a lot of the imagery should tie to that in some way. And that’s how I try to integrate all of that with it.

My favorite writers, from Dickens on, are writers who weren’t afraid to use imagery.

Imagery’s gotten a bad reputation, because there’s a lot of bad imagery. Everybody cites ‘a dark and stormy night’, and say’s that’s bad writing, except when that was written by Bulwer-Lytton it wasn’t a cliche.”

—Dean Koontz

Ray Bradbury, Zen and the Art of Writing:

“Once I learned to keep going back and back again to those times, I had plenty of memories and sense impressions to play with, not work with, no, play with. Dandelion Wine is nothing if it is not the boy-hid-in-the-man playing in the fields of the Lord on the green grass of other Augusts in the midst of starting to grow up, grow old, and sense darkness waiting under the trees to seed the blood.

I was amused and somewhat astonished at a critic a few years back who wrote an article analyzing Dandelion Wine plus the more realistic works of Sinclair Lewis, wondering how I could have been born and raised in Waukegan, which I renamed Green Town for my novel, and not noticed how ugly the harbor was and how depressing the coal docks and railyards down below the town. But, of course, I had noticed them and, genetic enchanter that I was, was fascinated by their beauty. Trains and boxcars and the smell of coal and fire are not ugly to children. Ugliness is a concept that we happen on later and become self-conscious about. Counting boxcars is a prime activity of boys. Their elders fret and fume and jeer at the train that holds them up, but boys happily count and cry the names of the cars as they pass from far places. And again, that supposedly ugly railyard was where carnivals and circuses arrived with elephants who washed the brick pavements with mighty steaming acid waters at five in the dark morning.”

—Ray Bradbury, Zen and the Art of Writing

If Tarzan, Winnie the Pooh, Anna Karenina, and Charles Foster Kane entered a crowded, opulent ballroom, they would notice four different versions of the crowd, and the room — four different interpretations of the same underlying reality. Their reactions would be completely idiosyncratic, dramatic, distinct… perhaps incompatible, perhaps contradictory, but certainly flavored with bold personality.

To a child, the world is enormous, and full of marvels; mysteries; magic.

To an adult, the same world might seem smaller, duller… a hostile ecosystem of petty harassments, financial penalties, burdensome regulations, unspoken etiquette, opaque hierarchies, relentless distractions, and low-level stressors.

Our personalities are drawn to focus on ambient details which confirm, reinforce, and validate the preexisting beliefs of a deeply entrenched worldview.

Beliefs may be empowering, or emasculating, but they are destined to shape the habitual pathways of our lives… guiding towards destiny, towards a fateful destination.

Identity is a compass, magnetically drawn to physically demonstrate the logical consequences of subconscious psychology.

One way or another, a belief system seeks to impose its metaphysical assumptions upon the body of the believer. Even absurd belief systems do this — either as tragedy, or comedy, through ruinous self-parody; the self-destructive wreckage of a clueless, misguided life.

Focus cultivates mood…

There is a habitual, subconscious choice to aim at the same daily targets, the same petty details, the same emotional landscape, which collectively accumulates into a lifestyle; career; family; community.

Focus sorts, sifts, selects, and then filters, ignoring the majority of available information, concentrating on a handful of attention-grabbing details…

The subtle contours of perception.

Blinks, and saccades.

The eyes are windows into the soul… and novels allow readers to perceive life through the eyes of a fictional stranger, to share their most terrifying and passionate experiences, to see the outside world through another person’s lens of predetermined beliefs, ambitions, insecurities, and prejudices.

The eyes are windows into the soul… novels allow readers to reverse-engineer the most hidden, intimate contours of a viewpoint character’s soul.

Perception is difficult to research; perception is difficult to perceive, and the human brain struggles to understand itself. Instinct propels us. Lust… greed… rage… curiosity.

All of this may seem very theoretical.

It’s a remote, abstract discussion which can seem to be a dense, self-referential vanity, coiled into circular loops of worthless, performative philosophical inquiry.

A waste of time.

But these are the sorts of questions which go overlooked.

When writing fiction, characters do not witness concrete reality in an empirical, objective, indisputable form. Their observations are always subjective. Colored and darkened by temperament, or tragedies.

The subjective nature of prose is one of the most useful tools available to a novelist.

Limited information is available to fictional characters, as opposed to the author, who (theoretically) has perfect knowledge of all the events happening in a story. The inner narration of a viewpoint character therefore flavors the story, and adds emotional texture, providing VOICE to the drama.

Every great, iconic character has a voice which is instantly recognizable.

Voice emerges from a distinct worldview: the clarity of intense passions, fierce hatreds; ambitions; affections; loyalties; rivalries; vendettas.

Furthermore, as characters learn and grow, they develop expertise in useful industries… they accumulate formative experiences which scar, strengthen, and transform them. As a result, characters develop insights into their professions, regions, relationships, and communities.

Sometimes characters are wrong, deeply wrong. Their actions are motivated by misguided, distorted worldviews.

Drama doesn’t require absolute truth, or mathematical precision… drama hungers for boldness; passion; conviction; intensity.

Fanatical, confident belief.

There is no place for mild, risk-averse heroes in a novel, movie, or television show.

Stories demand vivid colors.

Even hatred and prejudice are useful, in dramatic terms. Heroes and villains should be operatic, extraordinary, superhuman, and their affections, compulsions, obsessions, and vendettas must be likewise extraordinary.

For a lead character to be vulgar, or eccentric, or impulsive, is an asset.

That’s one of the main techniques which enchants fictional characters with a convincing simulation of life — to endow them with prominent strengths and flaws; steadfast friendships and bitter grudges.

Distinct, provocative opinions which instantly set them apart.

The other kind of character observation which lends credibility to the internal thoughts of a viewpoint hero is to seed the narrative with tiny, precious epiphanies that require authentic wisdom, the type of knowledge that requires personal, up-close experience — or meticulous, detailed research.

Language, culture, industry, social protocols, and the signaling mechanisms which human individuals, corporations, alliances, tribes, and civilizations use to communicate are one of the most elaborate areas of life. Daily interactions are seeded with deceits, obscurations, embellishments, distortions — a Darwinian form of linguistic competition which sometimes shrouds friendships in polite lies… but often masks a vicious battle for prestige, or resources.

Language is a weapon… perhaps the best weapon.

The pen is mightier than the sword… language is negotiated to determine which targets are acceptable, and what behavior is tolerated in a community.

In other words, the pen aims the sword.

Life is a competition.

Every area of life involves a battle for resources, status, authority, priority. Industries cloak themselves in the trappings of tradition and morality, to entrench their position, to protect themselves from scrutiny.

Glamorous myths emerge from this relentless struggle…

Favorable impressions are broadcast by the publicists of every major sector, congratulating themselves for performing a significant, beloved role in the maintenance and regular operation of civilization.

An important concept here is the idea of LEGIBILITY. How much information is available to a character? How much clarity exists? How significant is fog of war; the presence of hidden secrets, or inaccurate data?

One of the best ways to give fictional characters a sense of realism, a sense of Voice, is to tap into this game of unreliable information.

Public deceits are punctured by private truths, and these truths are delivered from the subjective viewpoint of fascinating viewpoint heroes. Small doses of insight are sprinkled into the narrative, interwoven amid the usual, predictable action and dialogue.

What results is a compelling, believable emotional texture which feels real to the audience, and builds trust between the chronicler and his customers.

Competition never stops; humans never quit trying to deceive each other, or to jostle for position, striving for dominance, seeking ascendancy. Because the struggle never ends, authors should never run out of opportunities to employ this technique, to deepen the texture of their narratives by puncturing misrepresentations and romanticized illusions, to bring life to characters by demonstrating the gulf between what people think, say, and do.

Below is a long list of colorful, evocative examples where various authors added texture to their stories and provided a memorable, dazzling voice to their characters:

1.)

“In my experience some of the most successful relationships are founded on lies and deceit. Since that's where they usually end up anyway, it's a logical place to start.”

—Andrew Niccol, Lord of War

2.)

“The next day we began to expand our operation. We started leaning on our social networks to recruit engineers and production managers. Within a quarter we had a staff of forty-five. I was always vague with the staff about our ultimate goals. The truth is, no one cares about how your startup is going to change the world, they just want stock options, a paycheck, and some buzzwords for their resume.

In retrospect, it was a cargo cult of cognition.”

—ZeroHPLovecraft, The Gig Economy

The Gig Economy - Zero HP Lovecraft (substack.com)

3.)

“Maybe he should turn around. Go back and tell them that’s what life was, a long series of things that didn’t go down the way you thought they would.

Hell with it. Either they’d figure it out or they wouldn’t. Most people never did.”

—Drive, James Sallis

4.)

“My hobbies include speculating on cryptocurrency and shitposting, which is where you put in minimal effort in creating your online presence so that you aren't culpable when its bland.”

—ZeroHPLovecraft, The Gig Economy

The Gig Economy - Zero HP Lovecraft (substack.com)

5.)

“Tension melted from his shoulders and he took a relaxed breath. People could talk all the shit they wanted to about strippers, but at least you knew where you stood with them. You could respect them. Strippers were God’s Chosen People. There was an integrity about them and what they did, and all parties went in knowing the rules of the game, and enjoyed the bittersweet narcotic of mutual disposability. The negotiating of its price was all up front and out in the open, unlike the regular nightclubs and bars where bitches postured like beasts in heat on the Serengeti yet spouted the “I’m just here to dance with my girlfriends/I’m not sure what I want right now” lines they regurgitated from whatever piece of Clit-Lit they had just read.”

—Samuel Finlay, Breakfast with the Dirt Cult

6.)

“Mister Sun did not like Los Angeles. He could never find a center to it. It seemed to him to hang on top of the world like a fallen constellation, resting on a rickety scaffold of endless, maddening road.

…

Only in Los Angeles would the production of a screenplay be an instantly forgotten piece of information. It marked him as unspecial. Just another of the ten million people aimlessly orbiting the movie business.”

—Warren Ellis, Dead Pig Collector

7.)

“Hladik had rounded forty. Aside from a few friendships and many habits, the problematic exercise of literature constituted his life. Like all writers, he measured the achievements of others by what they had accomplished, asking of them that they measure him by what he envisaged or planned. All the books he had published had left him with a complex feeling of repentance.”

—Jorge Luis Borges, The Secret Miracle

8.)

“‘Please don’t eat anything in that area,’ he says. It is him (bum bum BUMMM!), but I don’t yet know it’s him (bum-bum-bummm). I know it’s a guy who will talk to me, he wears his cockiness like an ironic T-shirt, but it fits him better. He is the kind of guy who carries himself like he gets laid a lot, a guy who likes women, a guy who would actually fuck me properly. I would like to be fucked properly! My dating life seems to rotate around three types of men: preppy Ivy Leaguers who believe they’re characters in a Fitzgerald novel; slick Wall Streeters with money signs in their eyes, their ears, their mouths; and sensitive smart-boys who are so self-aware that everything feels like a joke. The Fitzgerald fellows tend to be ineffectively porny in bed, a lot of noise and acrobatics to very little end. The finance guys turn rageful and flaccid. The smart-boys fuck like they’re composing a piece of math rock: This hand strums around here, and then this finger offers a nice bass rhythm… I sound quite slutty, don’t I? Pause while I count how many… eleven. Not bad. I’ve always thought twelve was a solid, reasonable number to end at.”

—Gillian Flynn, Gone Girl

9.)

“It was collaborating with the enemy, it was treason, it was betrayal of the rank and file. Diplomats and politicians were supposed to do those things, not soldiers.”

—Peter Watts, Blindsight

10.)

“The hospital administrator was on John’s vast payroll.

Bribery is cheaper business than one would think, so many people selling themselves for so little. He had a theory about this. Most of them felt lucky to be on the take at all, that any negotiation could ruin what they saw as a bonus for doing nothing. It was only in the extreme example that they’d have to do anything, the nature of their illicit employment being what they knew rather than what they did. This administrator knew of Peter’s existence. That was enough to get ten dollars a month for the rest of his life, which could end at any moment if John felt the man apply any pressure to their arrangement.”

—T. R. Hudson, The Perfect and the Wicked

11.)

“Abby sensed disaster and began talking about the church they had joined. It had four thousand members, a gymnasium and bowling alley. She sang in the choir and taught eight-year-olds in Sunday school. Mitch went when he was not working, but he’d been working most Sundays.

“I’m happy to see you’ve found a church home, Abby,” her father said piously. For years he had led the prayer each Sunday at the First Methodist Church in Danesboro, and the other six days he had tirelessly practiced greed and manipulation. He had also steadily but discreetly pursued whiskey and women.”

—John Grisham, The Firm

12.)

T. R. Hudson, Hard Boiled:

“She walked in the room with that pouty look on her face. I knew it was only a matter of time until I’d have her. I could tell that she was thinking the same thing. I had to light up a smoke just to calm myself down at the thought.

“You got a call from your doctor. He says you need to come in and see him. Speaking of which, you never gave me the healthcare info you promised. What insurance do we have?”

It was a great question. What insurance do any of us really have in this world? One day you can be beating up gays and commies for the government and the next, you gotta provide security while they parade down the street. Total madness.

“You’re a good girl, Doll, but you ask too many questions. You want healthcare? Go down to the bodega and get three packs of smokes and an apple. Put it on the expense account.”

—T. R. Hudson, Hard Boiled

Hard Boiled - The Writings of T.R. Hudson (substack.com)

13.)

Tucker Carlson:

“Politicians are a group that I despise on principle, because they tend to be soulless. And have barren and sad personal lives. So they spend their days trying to win affirmation from people they’ve never met. It’s pathetic.

But in real life — no, it’s true. They all have alcoholic or abusive fathers they’re trying to prove something to.

But in practice, in person, they’re all super charming. There’s not a politician in the world who’s not charming, that’s why they went into this business. It was either that or selling cars, and this was more lucrative, so they went into politics. So I like almost all of them when I meet them. You can’t not like them; they can talk about anything, they’ve mastered the art of shallow small talk over coffee.

That’s an acquired skill, and they’ve worked hard at it.”

—Tucker Carlson

14.)

“It was an ordinary day, a Friday, twenty minutes till lunchtime, five hours till quitting time and the weekend, ten months till vacation, thirty-seven years till retirement. Then the phone rang.”

—Jack Finney, Time and Again

15.)

Robert Heinlein, Starship Troopers:

“I see that I didn’t make any mention of how the Terran Federation moved from "peace" to a "state of emergency" and then on into "war." I didn’t notice it too closely myself. When I enrolled, it was "peace," the normal condition, at least so people think (who ever expects anything else?). Then, while I was at Currie, it became a "state of emergency" but I still didn’t notice it, as what Corporal Bronski thought about my haircut, uniform, combat drill, and kit was much more important — and what Sergeant Zim thought about such matters was overwhelmingly important. In any case, "emergency" is still "peace."

"Peace" is a condition in which no civilian pays any attention to military casualties which do not achieve page-one, lead-story prominence — unless that civilian is a close relative of one of the casualties. But, if there ever was a time in history when "peace" meant that there was no fighting going on, I have been unable to find out about it.”

—Robert Heinlein, Starship Troopers

16.)

T. R. Hudson, John Henry:

“George noticed that Frank was looking for sympathy, but it wouldn’t muster.

“I’ve lost sleep,” Frank admitted. “I kept hoping and praying that there would be some miracle solution to all my problems. I built this company fifty-three years ago. My grandfather was an immigrant. My father was a janitor. My son is an asshole. This is all I have. I’m sorry, but I would rather sacrifice part than lose it all.”

George could see the anguish in Frank’s eyes. Frank’s sincerity somehow made the bombshell easier to manage, but not by much. George was angry, but didn’t know who to be angry at. Vito may deserve an ass-kicking, but it was Frank who made the deal. George thought of his family. He could take the deal and keep his job and pay the bills and sleep in his bed with his loving wife, and he could continue as if nothing bad had happened. Frank offered George a lifeline, and why shouldn’t he take it? He was fifty-five years old, and although he still worked harder than men half his age, the years were gaining on him. He moved slower than he did a year ago. Way slower than he did five years ago. Retirement was always a distant mirage, a carrot that kept the horse moving, even if it never got any closer. I only had ten more years.”

—T. R. Hudson, John Henry

John Henry - The Writings of T.R. Hudson (substack.com)

17.)

“We walked down the cell row to a kind of open area at the end. I saw the fire door Spivey had used the night before. Beyond it was a tiled opening. Over the opening was a clock. Nearly twelve noon. Clocks in prisons are bizarre. Why measure hours and minutes when people think in years and decades?”

—Lee Child, The Killing Floor

18.)

“Sometimes Richard did think and feel like an artist. He was an artist when he saw fire, even a match head (he was in his study now, lighting his first cigarette): an instinct in him acknowledged its elemental status. He was an artist when he saw society: it never crossed his mind that society had to be like this, had any right, had any business being like this. A car in the street. Why? Why cars? This is what an artist has to be: harassed to the point of insanity or stupefaction by first principles. The difficulty began when he sat down to write.”

—Martin Amis, The Information

19.)

“You can't have a normal life anymore. You must know that. How can you have a girlfriend if you can't remember her name? Can't have kids, not unless you want them to grow up with a dad who doesn't recognize them. Sure as hell can't hold down a job. Not too many professions out there that value forgetfulness. Prostitution, maybe. Politics, of course.”

—Jonathan Nolan, Memento Mori (short story, basis of Christopher Nolan’s film Memento)

20.)

Bernice Bobs her hair, by F. Scott Fitzgerald:

“He wondered idly whether she was a poor conversationalist because she got no attention or got no attention because she was a poor conversationalist.”

…

“This was more in Bernice's line, but a faint regret mingled with her relief as the subject changed. Men did not talk to her about kissable mouths, but she knew that they talked in some such way to other girls.”

…

“Charley, who knew as much about the psychology of women as he did of the mental states of Buddhist contemplatives, felt vaguely flattered.”

…

“Yes, she was pretty, distinctly pretty; and to-night her face seemed really vivacious. She had that look that no woman, however histrionically proficient, can successfully counterfeit — she looked as if she were having a good time. He liked the way she had her hair arranged, wondered if it was brilliantine that made it glisten so. And that dress was becoming — a dark red that set off her shadowy eyes and high coloring. He remembered that he had thought her pretty when she first came to town, before he had realized that she was dull. Too bad she was dull — dull girls unbearable — certainly pretty though.”

—F. Scott Fitzgerald, Bernice Bobs Her Hair

21.)

“He observed, with satisfaction, that she was silenced by anger. He liked to observe emotions; they were like red lanterns strung along the dark unknown of another's personality, marking vulnerable points. But how one could feel a personal emotion about a metal alloy, and what such an emotion indicated, was incomprehensible to him; so he could make no use of his discovery.”

—Ayn Rand, Atlas Shrugged

22.)

“People here in Dardanelle and Russellville said, well, she hardly knew the man but it is just like a cranky old maid to do a "stunt" like that. I know what they said even if they would not say it to my face. People love to talk. They love to slander you if you have any substance. They say I love nothing but money and the Presbyterian Church and that is why I never married. They think everybody is dying to get married. It is true that I love my church and my bank. What is wrong with that? I will tell you a secret. Those same people talk mighty nice when they come in to get a crop loan or beg a mortgage extension! I never had the time to get married but it is nobody's business if I am married or not married. I care nothing for what they say. I would marry an ugly baboon if I wanted to and make him cashier. I never had the time to fool with it. A woman with brains and a frank tongue and one sleeve pinned up and an invalid mother to care for is at some disadvantage, although I will say I could have had two or three old untidy men around here who had their eyes fastened on my bank. No, thank you! It might surprise you to know their names.”

—Charles Portis, True Grit

23.)

"During all those last weeks I spent there, there was a peculiar evil feeling in the air — an atmosphere of suspicion, fear, uncertainty, and veiled hatred. You seemed to spend all your time holding whispered conversations in corners of cafes and wondering whether that person at the next table was a police spy.

"I do not know if I can bring home to you how deeply that action touched me. It sounds a small thing, but it was not. You have got to realize what was the feeling of the time — the horrible atmosphere of suspicion and hatred."

—George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia

24.)

Alan Glynn, The Dark Fields (Limitless):

“‘And shouldn’t all of these books have similar titles?’ I went on. ‘Something identifiable – mine for instance is Turning On: From Haight- Ashbury to Silicon Valley, so Dean’s could be, instead of just Venus, it could be… Shooting Venus: From… Pickford to Paltrow, or From Garbo to Spencer, something along those lines. Clare’s, if she confined it to boys, could be… Raising Sons: From Beaver to Bart. I don’t know. Give it a formula, make it easier to sell.’

There was a silence on the other end of the line, and then,

‘What do you want me to say, Eddie? It’s Friday afternoon. I’ve got deadlines today.’

I could picture Mark in his office now, lean and geeky, struggling to stay on top of his workload, an un-or half-eaten cheeseburger on his desk, a secretary he was in love with ritually humiliating him every time their eyes met. He had a windowless office on the twelfth floor of the old Port Authority Building on Eighth Avenue, and spent most of his life there – including evenings, weekends and days off.

I felt a wave of contempt for him.”

—Alan Glynn, The Dark Fields (Limitless)

25.)

“Karl could not, would not, hold the next question. “Pepper's shotgun and camping gear were found under one of the beds. How'd they get there?”

Patrick glanced up for a second as if surprised, then he looked away. Karl absorbed this reaction, because he would think about it many times over the next few days. A jolt, then a glance, and then unable to answer truthfully, a diversion to the wall.

The line from the old movie said, “When you commit a murder you make twenty-five mistakes. If you can think of fifteen of them, you're a genius.” Perhaps Patrick, in all his meticulous scheming, had simply forgotten about Pepper's things. In the rush of the moment, he had hurried a bit too much.”

—John Grisham, The Partner

26.)

George R. R. Martin, A Clash of Kings:

““You’ve heard these tidings of your brother?”

“Last night.” Conwy and his charges had brought the news north with them, and the talk in the common room had been of little else. Jon was still not certain how he felt about it. Robb a king? The brother he’d played with, fought with, shared his first cup of wine with? But not mother’s milk, no. So now Robb will sip summerwine from jeweled goblets, while I’m kneeling beside some stream sucking snowmelt from cupped hands. “Robb will make a good king,” he said loyally.

“Will he now?” The smith eyed him frankly. “I hope that’s so, boy, but once I might have said the same of Robert.”

“They say you forged his warhammer,” Jon remembered.

“Aye. I was his man, a Baratheon man, smith and armorer at Storm’s End until I lost the arm. I’m old enough to remember Lord Steffon before the sea took him, and I knew those three sons of his since they got their names. I tell you this — Robert was never the same after he put on that crown. Some men are like swords, made for fighting. Hang them up and they go to rust.”

“And his brothers?” Jon asked.

The armorer considered that a moment. “Robert was the true steel. Stannis is pure iron, black and hard and strong, yes, but brittle, the way iron gets. He’ll break before he bends. And Renly, that one, he’s copper, bright and shiny, pretty to look at but not worth all that much at the end of the day.”

And what metal is Robb? Jon did not ask. Noye was a Baratheon man; likely he thought Joffrey the lawful king and Robb a traitor. Among the brotherhood of the Night’s Watch, there was an unspoken pact never to probe too deeply into such matters. Men came to the Wall from all of the Seven Kingdoms, and old loves and loyalties were not easily forgotten, no matter how many oaths a man swore… as Jon himself had good reason to know. Even Sam — his father’s House was sworn to Highgarden, whose Lord Tyrell supported King Renly. Best not to talk of such things. The Night’s Watch took no sides.”

—George R. R. Martin, A Clash of Kings

27.)

Alan Glynn, The Dark Fields (Limitless):

“When I felt sufficiently awake, I stared at myself in the mirror for a while. It wasn’t the usual bathroom mugshot. I wasn’t bleary-eyed or puffy, or dangerous-looking, I was just tired – as well as all the other things that hadn’t changed since the day before, the fact that I was overweight, and jowly, and badly in need of a haircut. There was another thing I needed, too, but you couldn’t tell it from looking at me in the mirror – I needed a cigarette.

I tramped into the living-room and got my jacket from the back of the chair. I took the pack of Camels out of the side pocket, lit one up and filled my lungs with rich, fragrant smoke. As I was exhaling, I surveyed the room and reflected that being untidy was less a lifestyle choice of mine than a character defect.”

—Alan Glynn, The Dark Fields (Limitless)

28.)

T. E. D. Klein, Children of the Kingdom:

“If I sound less than reverent toward my elders, there’s a good reason: I am. No doubt I’ll be joining their ranks some day myself (unless I’m already food for worms, knocked down by an addict or a bus), and I’ll probably spend my time blinking and daydreaming like everyone else. Meanwhile, though, I find it hard to summon up the respect one’s supposed to feel for age. Old people have always struck me as rather childish, in fact. Despite their reputation, they’ve never seemed particularly wise.

Perhaps I just tend to look for wisdom in the wrong places. I remember a faculty party where I introduced myself to a celebrated visiting theologian and asked him a lot of earnest questions, only to discover that he was more interested in making passes at me. I once eavesdropped on the conversation of two well-known writers on the occult who turned out to be engaged in a passionate argument over whether a Thunderbird got better mileage than a Porsche. I bought the book by Dr. Kubler-Ross, the one in which she interviews patients with terminal cancer, and I found, sadly, that the dying have no more insight into life, or death, than the rest of us. But old people have been the biggest disappointment of all; I’ve yet to hear a one of them say anything profound. They’re like that ninety-two-year-old Oxford don who, when asked by some deferential young man what wisdom he had to impart after nearly a century of living, ruminated a moment and then said something like, “Always check your footnotes.” I’ve never found the old to be wiser than anyone else. They’ve never told me anything I didn’t know already.

But Father Pistachio… Well, maybe he was different. Maybe he was onto something after all.”

—T. E. D. Klein, Children of the Kingdom

29.)

Ayn Rand, Atlas Shrugged:

“When the train jolted forward, the blast of its whistle dying over the fields, she sat by the window, lighting another cigarette. She thought: It's cracking to pieces, like this, all over the country, you can expect it anywhere, at any moment. But she felt no anger or anxiety; she had no time to feel.

This would be just one more issue, to be settled along with the others. She knew that the superintendent of the Ohio Division was no good and that he was a friend of James Taggart. She had not insisted on throwing him out long ago only because she had no better man to put in his place. Good men were so strangely hard to find. But she would have to get rid of him, she thought, and she would give his post to Owen Kellogg, the young engineer who was doing a brilliant job as one of the assistants to the manager of the Taggart Terminal in New York; it was Owen Kellogg who ran the Terminal. She had watched his work for some time; she had always looked for sparks of competence, like a diamond prospector in an unpromising wasteland. Kellogg was still too young to be made superintendent of a division; she had wanted to give him another year, but there was no time to wait. She would have to speak to him as soon as she returned.

The strip of earth, faintly visible outside the window, was running faster now, blending into a gray stream. Through the dry phrases of calculations in her mind, she noticed that she did have time to feel something: it was the hard, exhilarating pleasure of action.”

—Ayn Rand, Atlas Shrugged

30.)

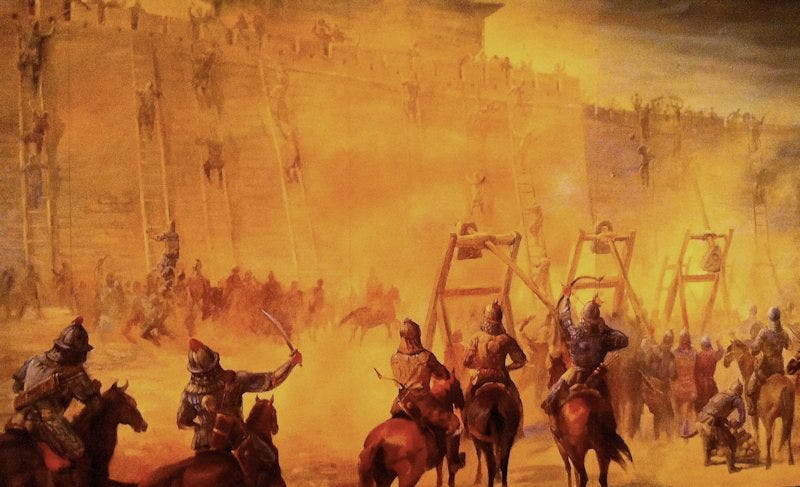

Jorge Luis Borges, Story of the Warrior and the Captive:

“The wars bring him to Ravenna and there he sees something he has never seen before, or has not seen fully. He sees the day and the cypresses and the marble. He sees a whole whose multiplicity is not that of disorder; he sees a city, an organism composed of statues, temples, gardens, rooms, amphitheaters, vases, columns, regular and open spaces. None of these fabrications (I know) impresses him as beautiful; he is touched by them as we now would be by a complex mechanism whose purpose we could not fathom but in whose design an immortal intelligence might be divined. Perhaps it is enough for him to see a single arch, with an incomprehensible inscription in eternal Roman letters. Suddenly he is blinded and renewed by this revelation, the City. He knows that in it he will be a dog, or a child, and that he will not even begin to understand it, but he also knows that it is worth more than his gods and his sworn faith and all the marshes of Germany. Droctulft abandons his own and fights for Ravenna.

…

When I read the story of this warrior in Croce's book, it moved me in an unusual way and I had the impression of having recovered, in a different form, something that had been my own. Fleetingly I thought of the Mongolian horsemen who tried to make of China an infinite pasture ground and then grew old in the cities they had longed to destroy; this was not the memory I sought.”

—Jorge Luis Borges, Story of the Warrior and the Captive

31.)

“Before Sandy's eyes, J. Murray was transformed from a hard-nosed advocate to a soulful mediator, a chameleon-like conversion common among lawyers who suddenly found themselves stripped of ammunition. He exhaled heavily, defeated, and sat low in his leather swivel, “They never tell us everything, do they,” he said. It was suddenly us versus them. Lawyers versus their clients. He and Sandy were really together now, and what were they to do?”

—John Grisham, The Partner

32.)

T. E. D. Klein, Black Man with a Horn:

“I looked through every book I could find with “Malaya” in its title. I read about rainbow gods and phallic altars and something called “the tatai," a sort of unwanted companion; I came across wedding rites and The Death of Thorns and a certain cave inhabited by millions of snails. But I found no mention of the Tcho-Tcho, and nothing on their gods.

This in itself was surprising. We are living in a day when there are no more secrets, when my twelve-year-old nephew can buy his own grimoire and books with titles like The Encyclopaedia of Ancient and Forbidden Knowledge are remaindered at every discount store. Though my friends from the twenties would have hated to admit it, the notion of stumbling across some moldering old “black book” in the attic of a deserted house — some lexicon of spells and chants and hidden lore — is merely a quaint fantasy. If the Necronomicon actually existed, it would be out in Bantam paperback with a preface by Lin Carter.”

—T. E. D. Klein, Black Man with a Horn

33.)

F. Scott Fitzgerald, Winter Dreams:

“Next evening while he waited for her to come down-stairs, Dexter peopled the soft deep summer room and the sun-porch that opened from it with the men who had already loved Judy Jones. He knew the sort of men they were--the men who when he first went to college had entered from the great prep schools with graceful clothes and the deep tan of healthy summers. He had seen that, in one sense, he was better than these men. He was newer and stronger. Yet in acknowledging to himself that he wished his children to be like them he was admitting that he was but the rough, strong stuff from which they eternally sprang.

…

But a week later he was compelled to view this same quality in a different light. She took him in her roadster to a picnic supper, and after supper she disappeared, likewise in her roadster, with another man. Dexter became enormously upset and was scarcely able to be decently civil to the other people present. When she assured him that she had not kissed the other man, he knew she was lying--yet he was glad that she had taken the trouble to lie to him.”

—F. Scott Fitzgerald, Winter Dreams

34.)

T. E. D. Klein, Children of the Kingdom:

“I missed the last train back to New York and was forced to take the eleven-thirty bus. It proved to be a “local,” wending its way through the shabby little cities of southern New England and pulling into a succession of dimly lit Greyhound stations far from the highway, usually in the older parts of town—the decaying ethnic neighborhoods, the inner-city slums, the ghettos. I had a bad headache, and soon fell asleep. When I awoke I felt disoriented. All the other passengers were sleeping. I didn’t know what time it was, but hesitated to turn on the light and look at my watch lest it disturb the man next to me.

Instead, I looked out the window.

We were passing through the heart of yet another shabby, nameless city, moving past the same gutted buildings I’d been seeing all night in my dreams, the same lines of cornices and rooftops, empty windows, gaping doorways. In the patches of darkness, familiar shapes seemed strange. Mailboxes and fire hydrants sprouted like tropical plants. Yet somehow it was stranger beneath the streetlights, where garbage cast long shadows on the sidewalk, and vacant lots hid glints of broken glass among the weeds. I remembered what I’d read of those great Mayan cities standing silent and abandoned in the Central American jungle, with no clue to where the inhabitants had gone. Through the window I could now see crumbling rows of tenements, an ugly red-brick housing project, some darkened and filthy-looking shops with alleys blocked by iron gates. Here and there a solitary figure would turn to watch the bus go by. Except for my reflection, I saw not one white face. A pair of little children threw stones at us from behind a fortress made of trash; a grown man stood pissing in the street like an animal, and watched us with amusement as we passed.

I wanted to be out of this benighted place, and prayed that the driver would get us through quickly. I longed to be back in New York. Then a street sign caught my eye, and I realized that I’d already arrived. This was my own neighborhood; my home was only three streets down and just across the avenue. As the bus continued south I caught a fleeting glimpse of the apartment building where, less than half a block away, my wife lay awaiting my return.

Less than half a block can make a difference in New York. Different worlds can co-exist side by side, scarcely intersecting. There are places in Manhattan where you can see a modern high-rise, with its terraces and doormen and well-appointed lobby, towering white and immaculate above some soot-stained little remnant of the city’s past—a tenement built during the Depression, lines of garbage cans in front, or a nineteenth-century brownstone gone to seed, its brickwork defaced by graffiti, its front door yawning open, its hallway dark, narrow, and forbidding as a tomb. Perhaps the two buildings will be separated by an alley; perhaps not even that. The taller one’s shadow may fall across the other, blotting out the sun; the other may disturb the block with loud music, voices raised in argument, the gnawing possibility of crime.

Yet to all appearances the people of each group will live their lives without acknowledging the other’s existence. The poor will keep their rats, like secrets, to themselves; the cooking smells, the smells of poverty and sickness and backed-up drains, will seldom pass beyond their windows. The sidewalk in front may be lined with the idle and unshaven, men with T-shirts and dark skins and a gaze as sharp as razors, singing, or trading punches, or disputing, perhaps, in Spanish; or they may sit in stony silence on the stoop, passing round a bottle in a paper bag. They are rough-looking and impetuous, these men; but they will seldom leave their kingdom for the alien world next door. And those who inhabit that alien world will move with a certain wariness when they find themselves on the street, and will hurry past the others without meeting their eyes.”

—T. E. D. Klein, Children of the Kingdom

35.)

Nico Walker, Cherry:

“I walk to the counter, with the gun down now so it’s pointed at the floor. There’s no sense in making a big deal out of this. One thing about holding up banks is that you’re mostly robbing women, so you don’t ever want to be rude. About 80% of the time, so long as you’re not rude, the women don’t mind when you hold up the bank; probably it breaks up the monotony for them. Of course there are exceptions; about 20% have a bad outlook. Like there was one lady, looked like Janet Reno, wouldn’t come off a cent more than $1800; she’d have seen everybody dead before she’d have come off another cent. She actually thought the bank was right. But this was a fanatic. Usually the tellers are pretty cool: you give them a note or tell them you’re there to do a robbery, and they go in the cash drawers and lay the money on the counter, and you take it and you leave and that’s all there is to it. Really it’s very civilized. It’s like a quiet joke you’ve shared with them. I say joke because it my case I don’t imagine there was ever one to believe I’d do anything serious if push came to shove, though I do make it a point to try and at least look a little deranged because I don’t want anyone getting in trouble on account of me. I have a lot of sadness in the face to make up for, so I have to make faces like I’m crazy or else people will think I’m a pussy. The risk you run is that sometimes people think you’re a crazy pussy. But I have to do what I can; otherwise her manager might say to her, “Why’d you give that pussy the money? You’re fired!” And she goes home and tells the kids there isn’t going to be any Christmas.”

—Nico Walker, Cherry

36.)

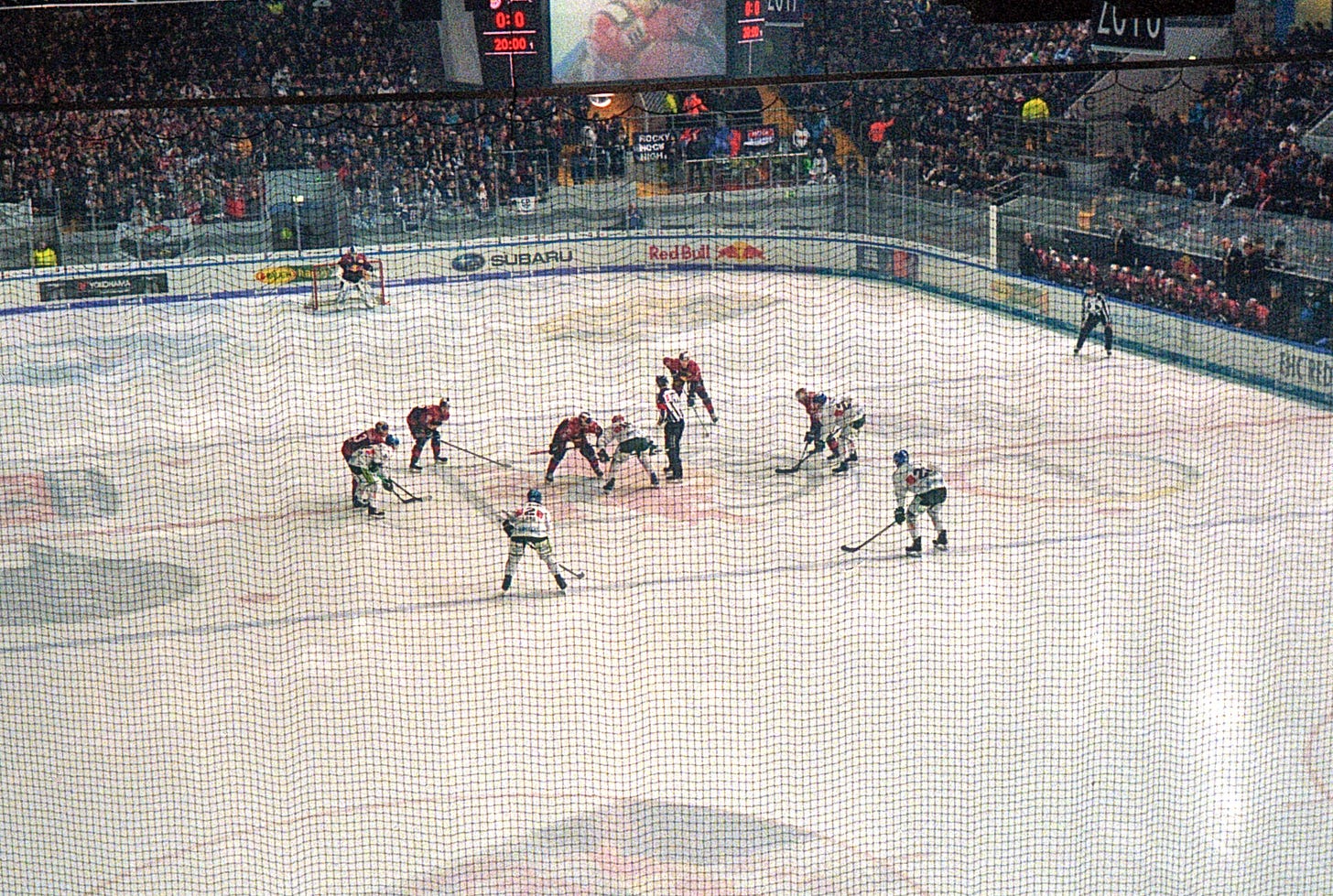

G. B. Joyce, The Code:

“Understand that the league is a systemic organization of hatreds. You might know a lot about the game but you’ll know nothing about the league until you accept this. It’s true of all of them: the players, the coaches, the general managers, the executives, the agents, and the owners. It goes from the high and mighty, the commissioner and his ilk in their plush Madison Avenue offices, right down to the lowest ranks, the scouts who sit next to me in arenas great and small.

No man is above the blackest animus. Could be a ref you jawed with. Could be your linemate who maybe knows your girlfriend better than he says. Could be the agent who rounds up his cut every time he thinks you’re not looking. Could be the massage therapist who rubbed you the wrong way. Could be the goalie farting in the whirlpool when you’re next in. If you are or were in the league in any capacity, even for the briefest time, somewhere somebody hopes that the next breath you draw will be your last. And guys won’t give up hating you when you’re dead. At that point the hate crosses over and they’ll draw the same exquisite satisfaction from your demise that they’d take from raising the Cup.

Hated and Hated By: They should be listed on a hockey card, right below the height, weight, position, and hometown. They’re a lot more important than your hometown, that’s for sure.

I’ve got my hates, too — not many, but deeply felt.

…

One sportswriter tagged me “the Journeyman’s Journeyman,” a pejorative squared. They always said I was “good in the room.” I was just being pragmatic. I wasn’t good enough on the ice to have an attitude. Gifted, I wasn’t. I had to think my way around the ice, and I took the same approach off it. I played in the minors with and against dozens of guys who were better than me but who never played a game in the league or landed a job there after hanging up their skates. Funny how in the minors I felt like a guy apart, like I got inside the league’s door only far enough to get it slammed on the instep of my skate.”

—G. B. Joyce, The Code

37.)

Neon Bag, Asylum Magazine: Volume Two: Issue Six: “Vers Le Vitesse D'Échappement”:

“I looked at Robert, forty years old, slouching into an unrecoverable smartphone-neck and a pant size that threatened to outpace his age. He had a boat he called a ship and didn’t own, a Maryland townhome the bank owned and he couldn’t legally defend, two good kids from a wife who owned him utterly and that was about it. Our college days were more promising, believe me, but he got busy with his now-wife and he withered, shriveled right up. His conservative vanity mag — the better circulated of his two basically vestigial organs — was small but mildly influential. It was funded more by benefactors than subscribers despite the constant and unctuous fundraisers.

…

He was expecting violence and wasn’t planning on helping: I had fought Bobby’s battles in elementary school, in high school and college, and he’d spent the rest of his life avoiding conflict altogether. Which explains how he got the second kid and the bully wife, and had finally buried himself in boat debt during a paroxysm of pretty understandable selfishness. He had never fought to know whether he could fight, or what life would be like knowing he had survived — or even won — a fight.”

—Neon Bag, Asylum Magazine: Volume Two: Issue Six: “Vers Le Vitesse D'Échappement”

VERS LE VITESSE D’ÉCHAPPEMENT - The Asylum (asylummagazine.ca)

38.)

Ernest Hemingway, The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber:

“Mrs. Macomber looked at Wilson quickly. She was an extremely handsome and well-kept woman of the beauty and social position which had, five years before, commanded five thousand dollars as the price of endorsing, with photographs, a beauty product which she had never used. She had been married to Francis Macomber for eleven years.

…

“I’ve dropped the whole thing,” she said, sitting down at the table. “What importance is there to whether Francis is any good at killing lions? That’s not his trade. That’s Mr. Wilson’s trade. Mr. Wilson is really very impressive killing anything. You do kill anything, don’t you?”

“Oh, anything,” said Wilson. “Simply anything.” They are, he thought, the hardest in the world; the hardest, the cruelest, the most predatory and the most attractive and their men have softened or gone to pieces nervously as they have hardened. Or is it that they pick men they can handle? They can’t know that much at the age they marry, he thought. He was grateful that he had gone through his education on American women before now because this was a very attractive one.

…

When she left, Wilson was thinking, when she went off to cry, she seemed a hell of a fine woman. She seemed to understand, to realize, to be hurt for him and for herself and to know how things really stood. She is away for twenty minutes and now she is back, simply enamelled in that American female cruelty. They are the damnedest women. Really the damnedest.”

—Ernest Hemingway, The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber

39.)

Adrian Tchaikovsky, Bear Head:

““Not saying the Emancipation Acts were a mistake but.” Thompson was saying. “When you can’t feel safe in. People are telling me it’s. Due a change, don’t you? The American citizen can’t be expected to.” Conversational fog to hide the forging of chains. And yet when Thompson lifted his head and smiled just so, mouth tight, eyes almost shut as though blinded by staring into his own genius, something in that impenetrable self-confidence communicated itself to the viewer, to the listener. I’m right, it told them. I’m right, not just in this but in my very being. So that people followed him, lifted him up, put him on a pedestal. Not like a man, a human leader who might be weighed and judged and required to do concrete things, but like the icon of a god, placed above them by right, impossible to challenge or question.

He was all handshakes and smiles when he came out: the author, the host, a couple of others he’d singled out for cultivating. Carole took note of names, scheduled a time to call them, sound them out. That indefatigable certainty bullied into the room, took up all the available space, became the gravity people orbited around. He ignored the stooge, still pale and shaking. Carole wondered if she should say something, because it was getting harder to find people to play the voice of reason opposite Thompson, and the last thing he wanted was for someone with actual convictions to start a genuine argument, quote facts, bring up any awkward contradictions from past speeches. But Thompson didn’t really do subtext. Someone spoke against him, that made them the enemy, even if they were doing it to his order. He was a man who lived his cover; he didn’t distinguish between who he was and the act he put on a lot of the time. Carole thought that was what people reacted to. She’d gone over the polls and the surveys obsessively, all the qualitative analysis from a legion of consultants tasked to find out just how it was that maverick politician Warner S. Thompson had come to dominate the nation’s conversation. People thought he was genuine, he said it straight, told them the truth. Despite the fact that he never quite told them anything at all. In the moment when he smiled and shook your hand, though; in the moment when he looked straight at the camera and beamed at the audience, you existed for him, and because his world was tiny, just a single point that was his own being, that meant you’d been admitted into the Divine Presence. You were real, for the second he acknowledged you.

She’d felt it herself. She saw it happening now. People fell over themselves to catch the edge of that spotlight that always seemed to be on the man.

Then he had broken abruptly from the crowd, and none of them existed any more. He took his personal light with him, that was just in his mind but that he believed in so firmly he could make others see it. He was grabbing Grubb by the shoulder, what looked like a friendly squeeze but was obviously painful.

…

He sat on the bed, jacket off, tie loosened, the lights turned low, and for a long time he did nothing. All that smile-and-gladhanding was gone from him, like a light had been switched off. His face had gone slack.”

—Adrian Tchaikovsky, Bear Head

40.)

Ernest Hemingway, The Snows of Kilimanjaro:

“It was not her fault that when he went to her he was already over. How could a woman know that you meant nothing that you said; that you spoke only from habit and to be comfortable? After he no longer meant what he said, his lies were more successful with women than when he had told them the truth.

It was not so much that he lied as that there was no truth to tell. He had had his life and it was over and then he went on living it again with different people and more money, with the best of the same places, and some new ones.”

You kept from thinking and it was all marvellous. You were equipped with good insides so that you did not go to pieces that way, the way most of them had, and you made an attitude that you cared nothing for the work you used to do, now that you could no longer do it. But, in yourself, you said that you would write about these people; about the very rich; that you were really not of them but a spy in their country; that you would leave it and write of it and for once it would be written by some one who knew what he was writing of. But he would never do it, because each day of not writing, of comfort, of being that which he despised, dulled his ability and softened his will to work so that, finally, he did no work at all. The people he knew now were all much more comfortable when he did not work. Africa was where he had been happiest in the good time of his life, so he had come out here to start again. They had made this safari with the minimum of comfort. There was no hardship; but there was no luxury and he had thought that he could get back into training that way. That in some way he could work the fat off his soul the way a fighter went into the mountains to work and train in order to bum it out of his body.

She had liked it. She said she loved it. She loved anything that was exciting, that involved a change of scene, where there were new people and where things were pleasant. And he had felt the illusion of returning strength of will to work. Now if this was how it ended, and he knew it was, he must not turn like some snake biting itself because its back was broken. It wasn’t this woman’s fault. If it had not been she it would have been another. If he lived by a lie he should try to die by it. He heard a shot beyond the hill.

She shot very well this good, this rich bitch, this kindly caretaker and destroyer of his talent. Nonsense. He had destroyed his talent himself. Why should he blame this woman because she kept him well? He had destroyed his talent by not using it, by betrayals of himself and what he believed in, by drinking so much that he blunted the edge of his perceptions, by laziness, by sloth, and by snobbery, by pride and by prejudice, by hook and by crook. What was this? A catalogue of old books? What was his talent anyway? It was a talent all right but instead of using it, he had traded on it. It was never what he had done, but always what he could do. And he had chosen to make his living with something else instead of a pen or a pencil. It was strange, too, wasn’t it, that when he fell in love with another woman, that woman should always have more money than the last one? But when he no longer was in love, when he was only lying, as to this woman, now, who had the most money of all, who had all the money there was, who had had a husband and children, who had taken lovers and been dissatisfied with them, and who loved him dearly as a writer, as a man, as a companion and as a proud possession; it was strange that when he did not love her at all and was lying, that he should be able to give her more for her money than when he had really loved.

We must all be cut out for what we do, he thought. However you make your living is where your talent lies. He had sold vitality, in one form or another, all his life and when your affections are not too involved you give much better value for the money. He had found that out but he would never write that, now, either. No, he would not write that, although it was well worth writing.”

—Ernest Hemingway, The Snows of Kilimanjaro

41.)

Leo Tolstoy, The Death of Ivan Ilyich:

“Now, as an examining magistrate, Ivan Ilych felt that everyone without exception, even the most important and self-satisfied, was in his power, and that he need only write a few words on a sheet of paper with a certain heading, and this or that important, self-satisfied person would be brought before him in the role of an accused person or a witness, and if he did not choose to allow him to sit down, would have to stand before him and answer his questions. Ivan Ilych never abused his power; he tried on the contrary to soften its expression, but the consciousness of it and the possibility of softening its effect, supplied the chief interest and attraction of his office. In his work itself, especially in his examinations, he very soon acquired a method of eliminating all considerations irrelevant to the legal aspect of the case, and reducing even the most complicated case to a form in which it would be presented on paper only in its externals, completely excluding his personal opinion of the matter, while above all observing every prescribed formality. The work was new and Ivan Ilych was one of the first men to apply the new Code of 1864.

…

Praskovya Fedorovna blamed her husband for every inconvenience they encountered in their new home. Most of the conversations between husband and wife, especially as to the children’s education, led to topics which recalled former disputes, and these disputes were apt to flare up again at any moment. There remained only those rare periods of amorousness which still came to them at times but did not last long. These were islets at which they anchored for a while and then again set out upon that ocean of veiled hostility which showed itself in their aloofness from one another. This aloofness might have grieved Ivan Ilych had he considered that it ought not to exist, but he now regarded the position as normal, and even made it the goal at which he aimed in family life. His aim was to free himself more and more from those unpleasantness and to give them a semblance of harmlessness and propriety. He attained this by spending less and less time with his family, and when obliged to be at home he tried to safeguard his position by the presence of outsiders. The chief thing however was that he had his official duties. The whole interest of his life now centered in the official world and that interest absorbed him. The consciousness of his power, being able to ruin anybody he wished to ruin, the importance, even the external dignity of his entry into court, or meetings with his subordinates, his success with superiors and inferiors, and above all his masterly handling of cases, of which he was conscious — all this gave him pleasure and filled his life, together with chats with his colleagues, dinners, and bridge. So that on the whole Ivan Ilych’s life continued to flow as he considered it should do — pleasantly and properly.

So things continued for another seven years.

…

At first she retorted and said disagreeable things to him, but once or twice he fell into such a rage at the beginning of dinner that she realized it was due to some physical derangement brought on by taking food, and so she restrained herself and did not answer, but only hurried to get the dinner over. She regarded this self-restraint as highly praiseworthy. Having come to the conclusion that her husband had a dreadful temper and made her life miserable, she began to feel sorry for herself, and the more she pitied herself the more she hated her husband. She began to wish he would die; yet she did not want him to die because then his salary would cease. And this irritated her against him still more. She considered herself dreadfully unhappy just because not even his death could save her, and though she concealed her exasperation, that hidden exasperation of hers increased his irritation also.

After one scene in which Ivan Ilych had been particularly unfair and after which he had said in explanation that he certainly was irritable but that it was due to his not being well, she said that if he was ill it should be attended to, and insisted on his going to see a celebrated doctor.

…

There was the usual waiting and the important air assumed by the doctor, with which he was so familiar (resembling that which he himself assumed in court), and the sounding and listening, and the questions which called for answers that were foregone conclusions and were evidently unnecessary, and the look of importance which implied that “if only you put yourself in our hands we will arrange everything — we know indubitably how it has to be done, always in the same way for everybody alike.” It was all just as it was in the law courts. The doctor put on just the same air towards him as he himself put on towards an accused person.

…

To Ivan Ilych only one question was important: was his case serious or not? But the doctor ignored that inappropriate question.

…

All this was just what Ivan Ilych had himself brilliantly accomplished a thousand times in dealing with men on trial. The doctor summed up just as brilliantly, looking over his spectacles triumphantly and even gaily at the accused. From the doctor’s summing up Ivan Ilych concluded that things were bad, but that for the doctor, and perhaps for everybody else, it was a matter of indifference, though for him it was bad. And this conclusion struck him painfully, arousing in him a great feeling of pity for himself and of bitterness towards the doctor’s indifference to a matter of such importance.

He said nothing of this, but rose, placed the doctor’s fee on the table, and remarked with a sigh: “We sick people probably often put inappropriate questions. But tell me, in general, is this complaint dangerous, or not? … ”

The doctor looked at him sternly over his spectacles with one eye, as if to say: “Prisoner, if you will not keep to the questions put to you, I shall be obliged to have you removed from the court.”

“I have already told you what I consider necessary and proper. The analysis may show something more.” And the doctor bowed.

Ivan Ilych went out slowly, seated himself disconsolately in his sledge, and drove home.”

—Leo Tolstoy, The Death of Ivan Ilyich

42.)

Donald Maass, The Breakout Novelist:

“The Psychology of Place:

Have you ever said to yourself, This place gives me the creeps? If so, you have experienced the psychological influence of inert physical surroundings. We are affected by what is around us.

If you have ever stood in a room designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, you know his interiors make you relax. The high-vaulting arches of Notre Dame can lift you to a spiritual plane. A simple Shaker meeting room does both things simultaneously; it is inner peace and fervent piety captured in four walls.

Anne Rivers Siddons is good at evoking the world of the tidewater Carolinas. In her 1997 novel Up Island, however, she brings her heroine Molly Bell Redwine north to Martha’s Vineyard to repair herself after a marital breakup. At the end of the summer season, Molly rents a small cottage on a remote upisland pond. The conjunction of house, landscape, and shattered spirit is deftly detailed:

“The house stood in full sun on the slope of the ridge that seemed to sweep directly up into the steel-blue sky. Below it, the lane I had just driven on wound through low, dense woodlands, where the Jeep had plunged in and out of dark shade. But up here there was nothing around the house except a sparse stand of wind-stunted oaks, several near-to-collapsing outbuildings, and two or three huge, freestanding boulders left, I knew, by the receding glacier that had formed this island. Above the house, the ridge beetled like a furrowed brow, matted with low-growing blueberry and huckleberry bushes. At the very top, no trees grew at all. I looked back down and caught my breath at the panorama of Chilmark Pond and the Atlantic Ocean. It was a day of strange, erratic winds and running cloud shadow, and the patch-work vista below me seemed alive, pulsing with shadow and sun, trees and ocean moving restlessly in the wind. Somehow it disquieted me so that I had to turn and face the closed door of the big, old house. I had come here seeking the shelter of the up-island wood, but this tall, blind house, alone in its ocean of space and dazzle of hard, shifting light, offered me no place to hide.”

The power of this passage results from more than the objects that it describes. Molly is uniquely affected by the light and landscape around her. Another character might have seen it as bright and refreshing. Molly, in her grief, experiences it as harsh and comfortless. See the difference? That is the psychology of place. You can deepen the psychology of place in your story by returning to a previously established setting and showing how your character’s perception of it has changed. You can also give your characters an active relationship to place, which, in turn, means marking your characters’ growth (or decline) through their relationships to their various surroundings. That, in turn, demands that you be writing in a strong point of view, regardless of whether your novel is first or third person. Do you have plain vanilla description in your current manuscript? Try evoking the description the way it is experienced by a character. Feel the difference? So will your readers.”

—Donald Maass, The Breakout Novelist