John Gardner, The Art of Fiction:

“By detail the writer achieves vividness; to make the scene continuous, he takes pains to avoid anything that might distract the reader from the image of fighting snakes to, say, the manner in which the image is presented or the character of the writer. This is of course not to say that the writer cannot break from the scene to some other—for instance, the conservationist rushing toward the snakes in his jeep. Though characters and locale change, the dream is still running like a movie in the reader’s mind.

The writer distracts the reader — breaks the film, if you will — when by some slip of technique or egoistic intrusion he allows or forces the reader to stop thinking about the story (stop “seeing” the story) and think about something else.

Some writers — John Barth, for instance — make a point of interrupting the fictional dream from time to time, or even denying the reader the chance to enter the fictional dream that his experience of fiction has led him to expect.

We will briefly examine the purpose and value of such fiction later. For now, it is enough to say that such writers are not writing fiction at all, but something else, metafiction.

They give the reader an experience that assumes the usual experience of fiction as its point of departure, and whatever effect their work may have depends on their conscious violation of the usual fictional effect. What interests us in their novels is that they are not novels but, instead, artistic comments on art.

…

I may as well add that I do not give much emphasis here to the various forms of unconventional fiction now popular in universities. Since metafiction is by nature a fiction-like critique of conventional fiction, and since so-called deconstructive fiction (think of Robert Coover’s story “Noah’s Brother”) uses conventional methods, it seems to me more important that young writers understand conventional fiction in all its complexity than that they be too much distracted from the fundamental.

…

Art does not imitate reality (hold the mirror up to nature) but creates a new reality. This reality may be apposite to the reality we walk through every day — streets and houses, mailmen, trees — and may trigger thoughts and feelings in the same way a newly discovered thing of nature might do—a captured Big Foot or Loch Ness monster— but it is essentially itself, not the mirror reflection of something familiar. The increasingly sharp recognition that art works in this way has generated the popularity, in recent years, of formalist art — art for art’s sake — and metafiction, of which we spoke earlier. The general principle of the former has been familiar for centuries. The first modern thinker to define the mode clearly may have been Robert Louis Stevenson in his preface to the Chesterfield edition of the translated Works of Victor Hugo. There Stevenson pointed out that all art exists on a continuum between poles he calls “objective” and “subjective.” At one extreme, the subjective, we have novels like those of Hugo, wherein we feel as we read that we are among the French mobs, surrounded by noise and smoke, transported from the room in which we read to Hugo’s imaginary Paris. At the other extreme we have Fielding’s Tom Jones, wherein we are never allowed to imagine for long that the hero is a “real” young man.

…

All literary parodists are inescapably creators of objective, or formalist, art. The parody becomes meaningless the moment we forget that the work is a literary object jokingly or seriously commenting on another literary object. In ordinary “realistic” fiction — what Robert Louis Stevenson would call subjective fiction — the writer’s intent is that the reader fall through the printed page into the scene represented, so that he sees not words and fictional conventions but the dream image of, say, a tumbleweed crossing Arizona. In formalist fiction we are conscious mainly of the writer’s art, or of both the tumbleweed and the art that makes it tumble.

…

“It is, as we’ve seen, this same nervous fascination with art’s untrustworthy character that has led to the popularity of metafiction, the piece of fiction on the subject of making fiction. Some of the more interesting recent examples — some of the less boring — are William Gass’s Willie Master’s Lonesome Wife, Ron Sukenick’s “What’s Your Story?” and John Barth’s “Life-Story.”

A central concern in all such fiction is the extent to which technique or medium may be art’s sole message.

One of the most elegant of recent American metafictions is John Barth’s “Lost in the Funhouse,” the story of a boy who goes to a fun-house with his older sister and her lover, a sailor. All that is moving and beautifully written in the story, by customary standards, Barth interrupts with comments from real or imagined manuals on the art of fiction. We like and affirm the story’s unsophisticated lovers, responding to the beauty of the prose that represents them; but the constant interruption of that prose with comments on how effective prose is written makes us irritably conscious of the extent to which moving prose is not natural but achieved. As a result, we doubt our naive response to the lovers, as Barth intends us to. We share — as in ordinary fiction we are never meant to do — the doubts and problems of the artist, but also his pleasure in his work, and in doing so lose the innocence of our delight in the funhouse and the experience of the lovers. Like the bright younger brother, we get no real pleasure from the sensations of life’s funhouse; we slip in to where the lovers are pulled and become “lost.”

Barth is not claiming that masterful technique is a thing to be avoided but only that, if possible, once one has captured it one should keep it on its chain.

On one hand, showy technique is thrilling, as much in a work of fiction as in the work of a brilliant trapeze artist or animal trainer. No one would ask that the master artist hide his abilities. On the other hand, cleverness can become its own end, subverting higher ends, as when style overshadows character, action, and idea. The question is whether the artist can ever hold a balance between subject and presentation. Perhaps it is in the nature of art that actuality must be murdered, as it is in “Ligeia,” and that what art brings forth is not some higher reality but a blood-stained thing that, like Madeline Usher, can flicker with apparent life for only an instant before collapsing back to death.”

—John Gardner, The Art of Fiction:

Metafiction is a bizarre, recursive topic:

Stories about stories.

Dreams within dreams… plays within plays… books which allude to literature… comics that depict comic books… films which discuss movies… metafiction comments upon the nature of entertainment itself. This is a big risk. Fiction requires suspension of disbelief; stories cannot succeed if the audience refuses to emotionally invest themselves in the narrative. Any kind of metafiction reminds the audience they are participating in a simulation, and threatens to disrupt their pleasant daydreams.

Breaking the fourth wall can often elicit a brief laugh. This abrupt joke will almost always work. Deadpool regularly violates the conventional rules of storytelling by referencing his status as a fictional comic book character in a ridiculous world of cartoon superheroes. This strategy of purposeful deconstruction is convenient and comedic in the short-term, but destructive of the long-term narrative.

Caveat emptor.

Beware temptations and shortcuts which lead travelers astray, for such paths end in solemn desolation, anguish, and perdition.

Counterfeit dollars spend the same as any other dollars… until they don’t. When trust is destroyed, rebuilding a broken relationship is more difficult, expensive, and time-consuming than it would have been to simply maintain the original loyalties, and reciprocal obligations.

That warning should be shared upfront.

Any storytellers considering the inclusion of metafiction should realize: You only have one option, which is to insert this technique fluidly; skillfully; thoughtfully; masterfully. If the novelty doesn’t work, you must fix it, and if it can’t be fixed, you need to cut it. A few drops of gasoline will ruin a glass of lemonade. Some mistakes are more damaging, and capture more attention, than conventional errors.

Handle with caution.

The logical question is to ask: why do artists ever bother with metafiction? If we accept that fiction is a simulation, and metafiction comments upon that simulation by drawing attention to the mechanical construction of narrative illusions, which risks alienating an engaged audience from the entertainment they desire, why should anyone attempt this sort of aesthetic?

If properly asked, then properly answered, an exploration of metafiction should teach us how to apply pioneering, experimental methods drawn from literature and cinema’s avant-garde frontier. And by understanding the frontier, by understanding the functions and ramifications of novelty, we should also achieve a renewed clarity into how stories operate at the simplest, most fundamental level.

Where does metafiction come from?

How did this strain of aesthetic expression originate?

Metafiction is a response to the failures, limitations, imperfections, and artifice of fiction.

Fiction is an illusion.

And there are a lot of flawed illusions, which fail to engage their audience, or to persuade fans that their world feels real.

There’s a lot of bad art. Hence the expression “there’s a thousand channels, and nothing on Television.”

Artists have a lot to say about art; they dedicate their lives to it. Nobody understands cities better than the architects who design them. Nobody understands lighting better than a photographer, who frames subjects at all times of day, manipulating aperture and distance to achieve bokeh — an elegant, focused foreground paired with a blurred, indistinct background.

Nobody understands body language and facial expressions better than an actor, who must inhabit their assigned character, performing a role — because the immutable secret of art is that before you persuade an audience, you must first persuade yourself.

Some artists are frustrated by mediocre versions of their craft: bad movies, books, comics. Others become curious.

Properly implemented, metafiction adds an extra layer to a comic; movie; novel, or television show:

On one level, the plot tells a superficial and literal story of dramatic tension, conflict, suspense, revelation, transformation, and resolution. On a second level, the characters act out a religious parable, a morality play, and their lives progress in metaphorical, allegorical fashion to organically stumble across and discover a spiritual thematic epiphany, some kind of valuable insight or personal lesson — even if the eventual lesson is that there is no lesson, even if the message is that life in our universe is a random chaotic experience devoid of any higher message. Nihilism requires precise structure to effectively demonstrate to a real world audience, portrayed through the struggle and defeat of optimistic characters who search for a hidden truth or a metaphysical sense of belonging. On a third level, if we choose to insert metafiction into an otherwise perfectly adequate narrative, the inclusion of metafiction comments upon stories with a sort of ironic and self-aware process of internal dissection — which opens up a new horizon of narrative possibilities, aesthetic sensibilities, and modes of artistic expression.

Stories can operate on more than three levels. And they regularly do.

But the above summary simplifies the process of how various layers of a narrative interact together with synergy in order to produce our ultimate goal: a gorgeous, multifaceted tapestry. Every part of a story must serve a purpose. Each component must combine together into something larger and more beautiful.

In Hamlet, Shakespeare uses a play within a play entitled “The Murder of Gonzago; or, The Mousetrap” as part of the elaborate intrigue and revenge scheme Hamlet undertakes against his uncle Claudius, who Hamlet suspects murdered his father.

This metafictional play within a play is designed by Hamlet to mirror the circumstances of his father’s death. Searching for guilt, probing for hidden malice, Hamlet closely observes the reactions of King Claudius during the performance, and he says to himself, “The play’s the thing, Wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the king.”

It’s a very convoluted and impractical strategy.

Hamlet’s plan is needlessly elaborate and inefficient, but this same implausible approach is what makes the narrative so dramatic, theatrical, and delightful.

Adventures are supposed to be bigger than life. More colorful. More dangerous. More suspenseful. Embedded with symbolism, and subtle indications of philosophical intent.

Metafiction adds another layer to a story. The additional layer mirrors, juxtaposes, accentuates, or amplifies the primary storyline. The author plays a game with the audience. The game’s rules explore how separate layers of fiction blend together to produce exotic effects. Rarely does the inserted metadrama impact the actual events of the main plot. More often, metafiction combines with the primary storyline through the power of suggestion and ambiguity. The events of a plot are literal. Metafiction is symbolic, and allows audiences to solve a puzzle themselves, as they analyze the implicit messages and hidden meanings which are buried and sealed into the skeleton of the story.

Consider Hamlet’s play within a play.

“The Murder of Gonzago; or, The Mousetrap”.

A trap for a king… planted to achieve revenge.

Hamlet’s father comes to him as a ghost. The ghost warns Hamlet that his uncle King Claudius murdered Hamlet’s father (also named Hamlet). Prince Hamlet is unsure whether this supernatural event is real, can be trusted, or is simply a dreamlike hallucination. Hamlet chooses “The Murder of Gonzago; or, The Mousetrap” to test King Claudius, but also to test himself, because Prince Hamlet lacks confidence in whether his father truly appeared to him as a phantom oracle.

The result is absurd, byzantine complexity which borders on comedic foolishness.

To summarize, Hamlet interprets the reaction of Claudius interpreting the play to determine the potential criminal guilt of King Claudius, and to interpret the veracity of his own supernatural experiences.

The logic here is cartoonish.

Preposterous.

But this complexity creates gaps, errors, and misunderstandings, which allow the narrative to unfold in unpredictable, thrilling directions.

Some additional examples…

In the anime “Spy × Family”, a spy named Loid Forger assembles a pair of strangers to pretend to be his wife and daughter, using his undercover pseudo-family to infiltrate a dangerous target. The young girl of family enjoys watching television cartoons, to an obsessive extent. Her favorite show is called “Spy Wars”.

“Spy Wars” is mostly used for comedic purposes, illustrating the divide between the public’s entertainment-oriented perception of espionage, versus the reality of a stressful, paranoid, and dangerous profession. Sometimes “Spy Wars” also provides exposition, advances the plot, or reflects an episode’s theme.

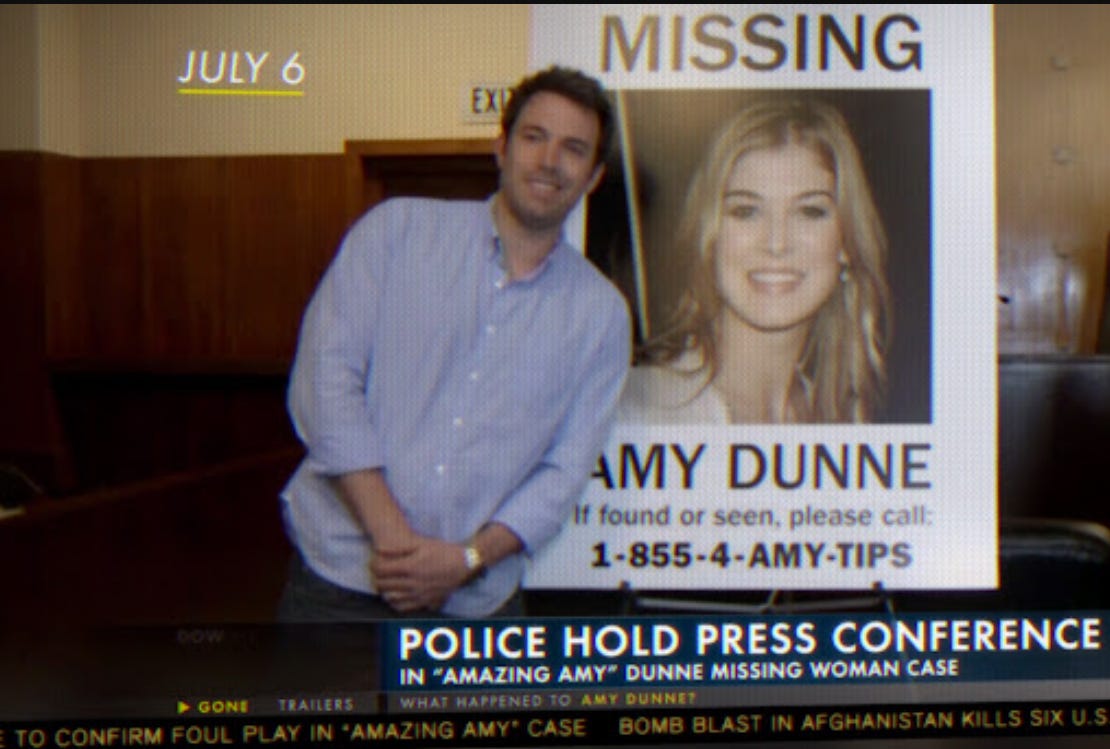

In Gillian Flynn’s “Gone Girl”, a marriage between urban strivers endures tremendous stress after both husband and wife lose their prestigious, trendy jobs, and they are forced to move back to a dying, blue-collar small town, one of America’s many neighborhoods to be abandoned and hollowed out by a globalized economy. The result is humiliation, despair, and a loss of purpose. Before, Amy and Nick Dunne enjoyed life among the glittering, beautiful caste of New York’s useless intellectuals. They embodied a certain kind of striver ideal: they were charming, sexy, intelligent, sophisticated, and educated to a kind of ironic detachment with the cliched patterns of their own lives. Both were brilliant, underachieving writers, and they bring that kind of overeducated, self-deprecating analytical lens to every mundane experience.

Downward mobility corrodes their once-happy marriage.

Bitterness and regret grows to consume them.

Pent-up rage simmers, then builds, and builds, boiling towards a volcanic crescendo.

This sense of irony manifests with witty, cynical humor, an awareness of how people live in literature, movies, and television, and a sort of resigned disgust observing themselves repeating the same cliched desires and ambitions, the same cliched tragedies and mistakes as every other couple.

That kind of irony undercuts every scene; Amy and Nick Dunne are always analyzing their own lives more as a stranger, an observer, than as a participant.

In particular, Amy Dunne’s chapters feature a series of metafictional quizzes, which speak to her former profession as an overeducated psychology major who used that degree to write trite online quizzes — a trivial and meaningless job. Through quizzes, Amy Dunne considers the stresses and tension of her dysfunctional marriage, her downwardly mobile family, and her unsuccessful career, and presents herself with a range of options — how to respond to the accumulation of discontent in her life. These quizzes are used to demonstrate the strain of Amy’s false positivity, and the increasing effort she dedicates to maintaining a positive attitude and a polite facade as her life deteriorates.

It’s a beautiful example of metafiction, which presents the real-world audience with a familiar discontent, but communicates with a clever, exotic presentation.

Alan Moore, Alan Moore’s Writing for Comics: Volume One:

“All right… in the previous Lord knows how many pages, we have considered different approaches to structure, storytelling, environment, and characterization — along with the nature of a plot, and the importance of a central idea. Bearing all of the above notions in mind, we can finally proceed to start work on the script itself.

We have an idea we wish to communicate, and a plot that underlines and reveals the idea in an interesting way.

We have solid, rounded characters for the story to happen to, and an equally solid and credible world for it to happen in.

The first step is to take our story, which presumably we will have arrived at with an eye to how many pages are available to print it in, and see exactly how well it fits into the given restrictions that we have.

As an example for how this process works, I’d cite 1985’s Superman Annual #11. The idea behind the story was to examine the concept of escapism and fantasy dreamworlds, including happy times in the past that we look back and idealize, and long-for points in the imagined future when we will finally achieve whatever our goal happens to be. I wanted to have a look at how useful these ideas actually are, and how wide the gap is between the fantasy and any sort of credible reality.

It was a story, if you like, for the people I’ve encountered who are fixated upon some point in the past where things could have gone differently — or who are equally obsessed with some hypothetical point in the future when certain circumstances will have come to pass, and they can finally be “happy”. People who say, “If only I hadn’t married that man or that woman. If only I’d stayed in college, left college earlier, settled down, gone off to see the world, got that job I turned down…” or who say, “When the mortgage is paid off, then I can enjoy myself. When I’m promoted and I get more money, then I can have a good time. When the divorce comes through, when the kids are grown up, when I finally manage to get my novel published…” These people are so enslaved by their perception of the past and future, that they are incapable of properly experiencing the present until it’s vanished.

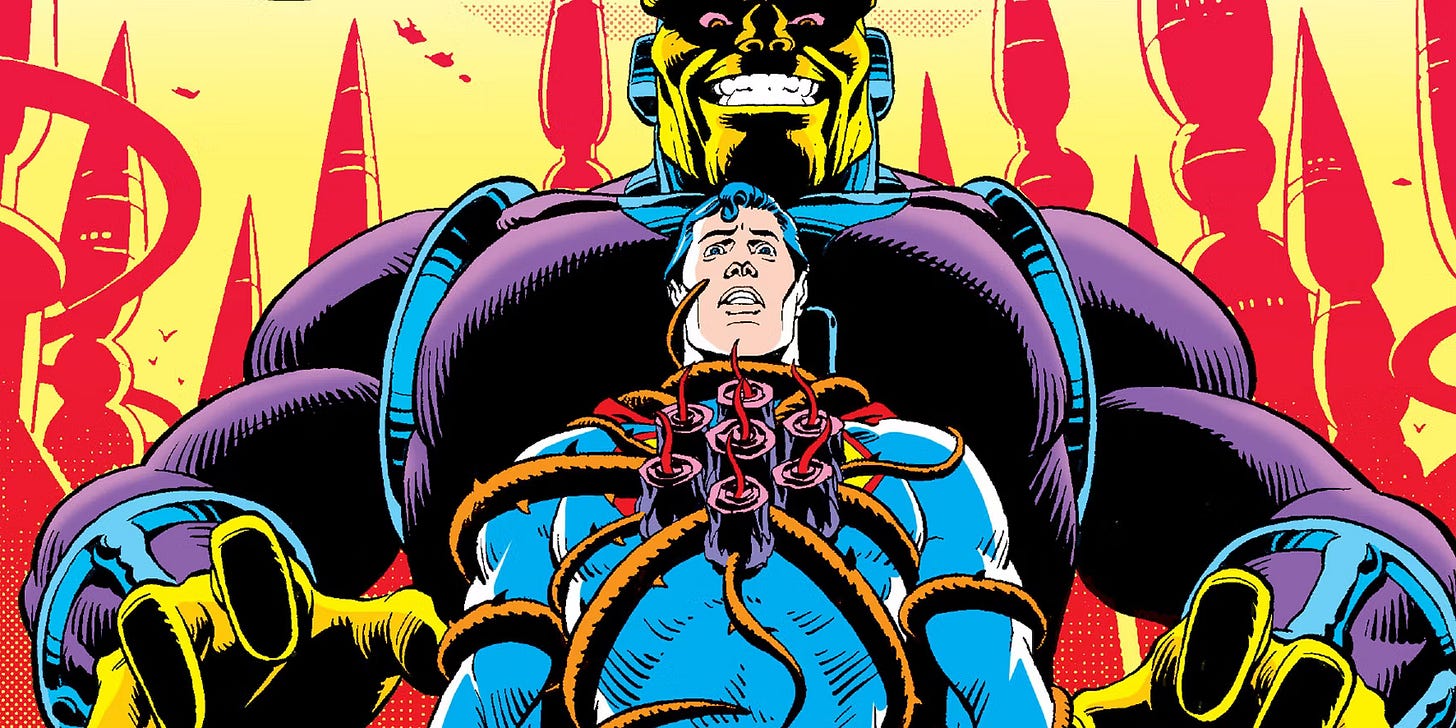

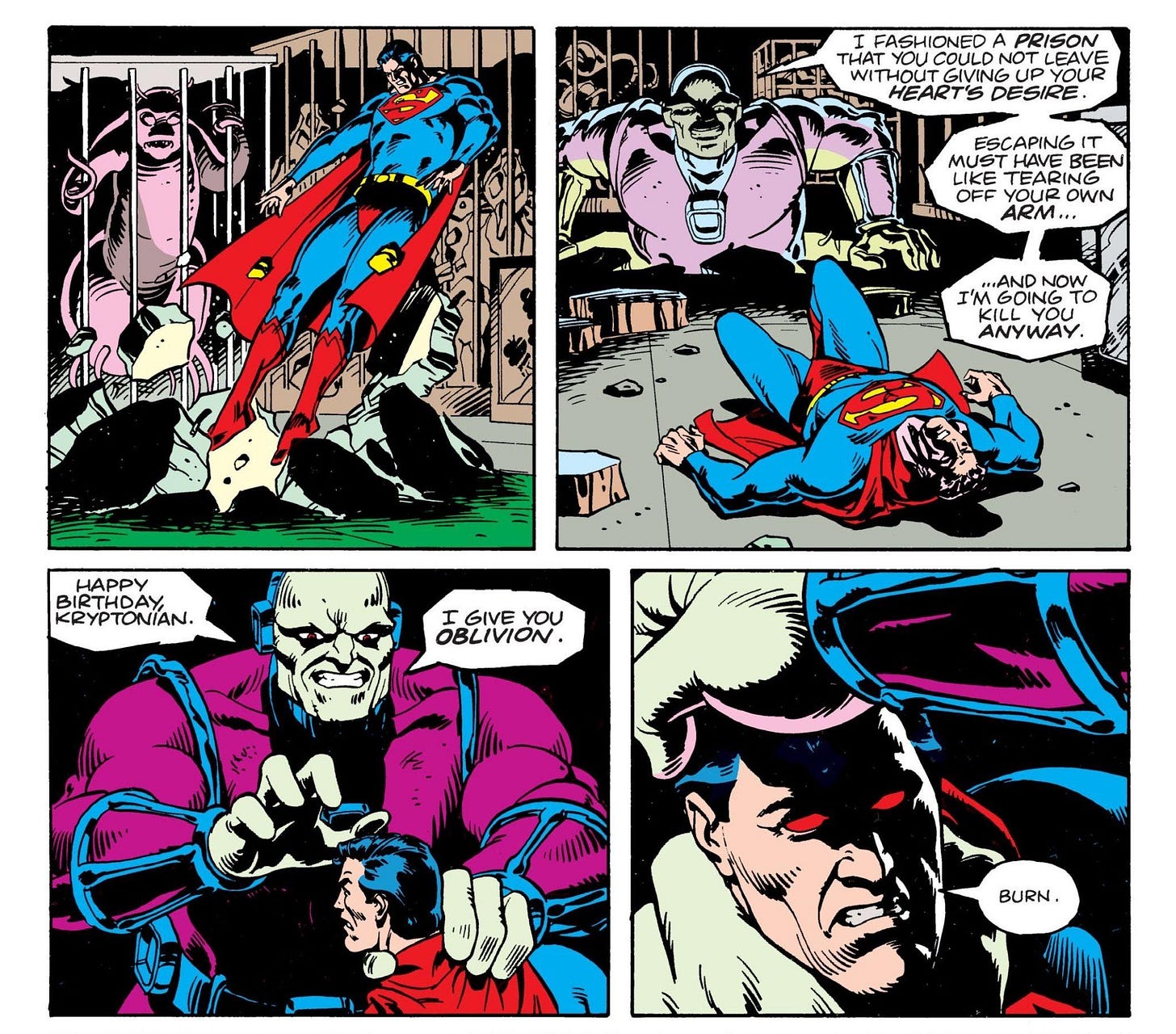

The plot that I chose to get that idea across involved Superman’s mind being enslaved by an organic telepathic parasite that fed him an illusion of his heart’s desire… a planet Krypton that never blew up.

This is part of a plot by Superman’s alien enemy Mongul, who wants Superman out of the way so that he can take over the universe, or whatever these tyrant types usually aspire to. The story takes place on Superman’s birthday, in the Fortress of Solitude, with simultaneous sequences going on inside Superman’s mind as he imagines himself on the world of Krypton as it would have been if it had never exploded.

In the course of the story, we see that such an eventuality might not have been as happy as it looks at first glance, finally leading Superman to throw off the fantasy and see it for what it is. At the same time, he sees his useless nostalgia for a vanished planet as it really is, and learns something about himself from the experience.

Okay… the problem is how to present that plot and its attendant idea within the restrictions that are imposed by the length of the book, the market it is aimed at, and so forth.

The most immediate and concrete restriction is that the book is 40 pages long. This means I must fit my story into that precise length, without it appearing either crammed or padded out unnecessarily. Thus, my first step is usually to take a piece of paper and write the numbers one to 40 down the left-hand side. I then start to sketch in the scenes about which I already have some ideas, and try to work out how many pages they will take up.

I’ve already worked out that I want to present a contrast between the world of Krypton in Superman’s dreams and the external reality of his situation, standing paralyzed in the Fortress of Solitude with an alien fungus clinging to his chest and feasting from his bio-aura.

In order for this to work, I need something interesting to be going on in the Fortress of Solitude while Superman is asleep, so that I can cut between an involving scene in the dreamworld and an equally engaging scene taking place simultaneously in the “real world”.

Since in terms of the plot it happened to be Superman’s birthday, it seemed logical that a couple of his superhuman pals might be visiting and provide the opportunity for some interesting incidental conflict with Mongul, the villain of the piece, who is also visiting the Fortress to survey his handiwork.

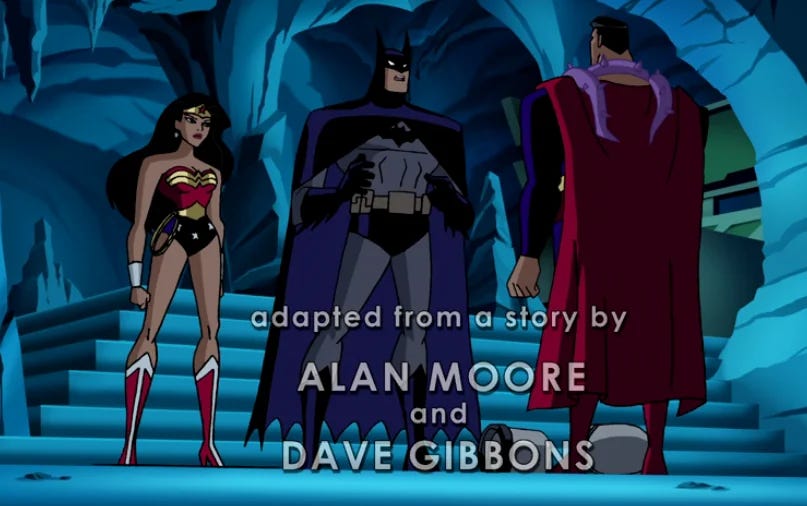

Given all this, I sat down and worked out a sequence of events that appeared logical, and that described what happened to Superman’s chums (Wonder Woman, Batman, and Robin, as it turned out; I originally wanted to use Supergirl, but then Julie Schwartz informed me that she’d be popping her bright red clogs during Crisis on Infinite Earths and suggested that I use Wonder Woman instead) from their arrival at the Fortress bearing presents for Superman.

…

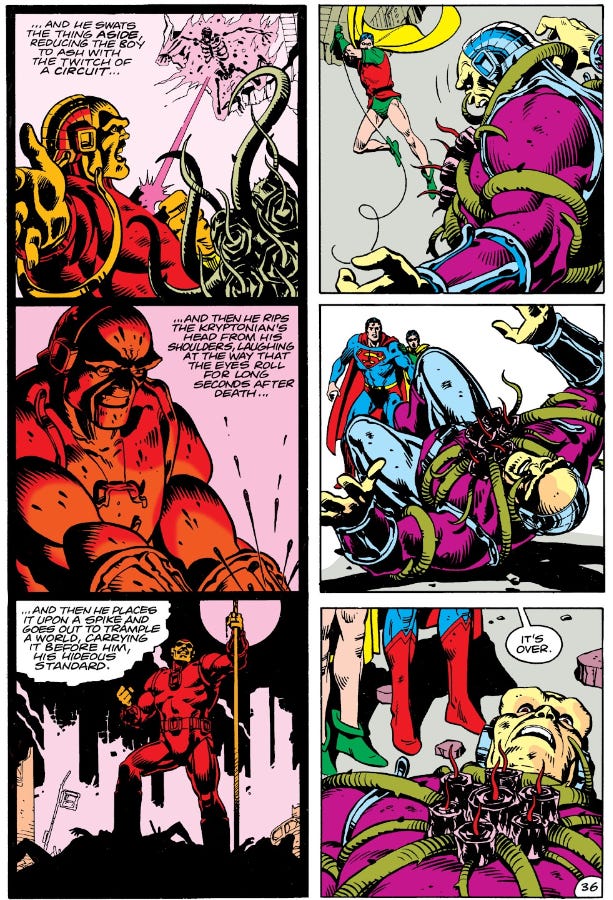

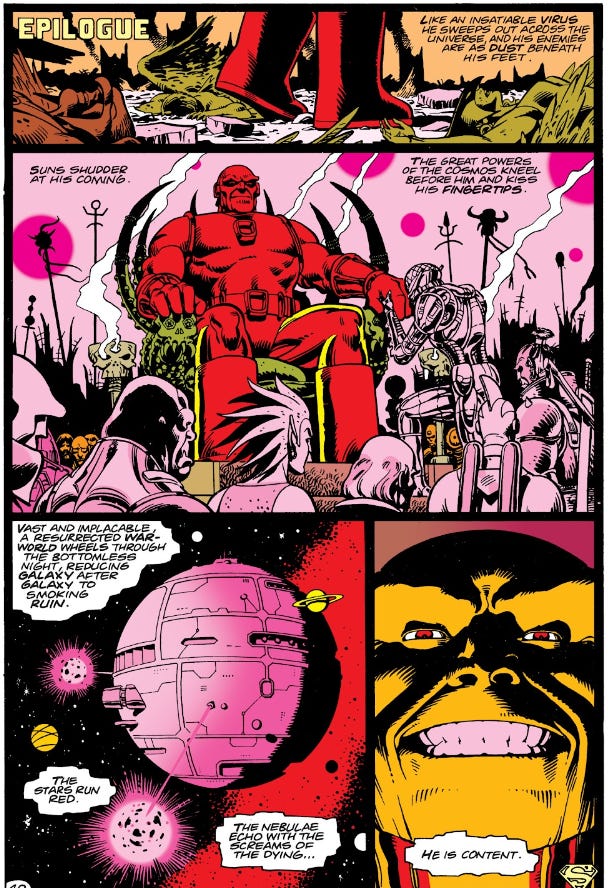

Mongul is finally subdued by the organism with which he had intended to trap Superman. After a three-page aftermath in which the heroes relax and chat after the battle, we have Batman presenting his specially bred “Krypton” rose, which has been crushed and killed during the fighting. Superman calmly accepts the death of the rose, and by extension the death of Krypton, providing a neat emotional point at which to bring the story to a close with the central idea explored and at least partially resolved. The final page, mirroring the first page of the whole story, lets us have a glimpse into the terrible and bloodthirsty dream reality conjured by Mongul under the parasite’s influence, showing that he is more hopelessly trapped within his own dreams than Superman ever could be, and providing a counterpoint to Superman’s eventual success with his eventual failure.”

—Alan Moore, Alan Moore’s Writing for Comics: Volume One

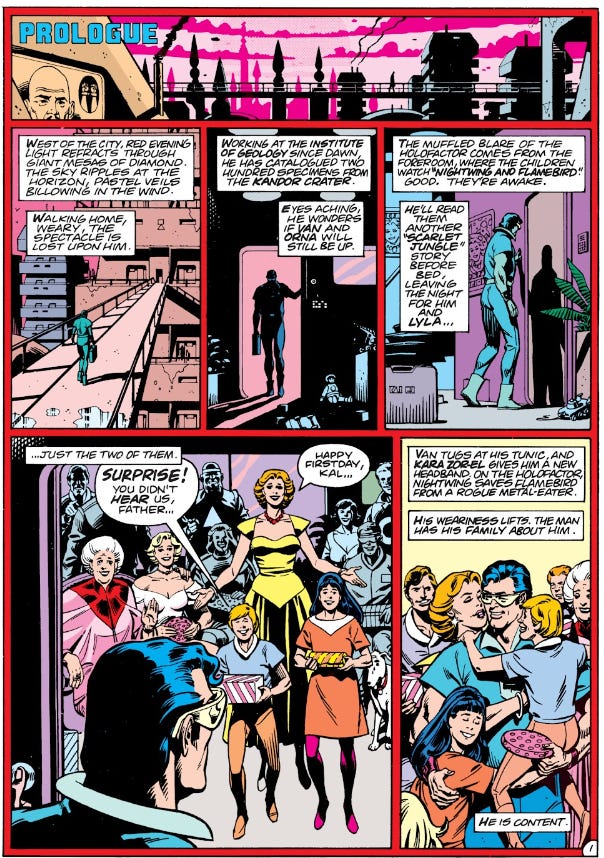

Three fantasies play out in the comic pages above: Superman dreams that Krypton was never destroyed, Batman dreams that his parents were never murdered, and Mongul dreams that he has triumphantly conquered the universe.

Each sequence of hallucinations features elaborate prose descriptions, which end on the phrase, “He is content.” It’s a subtle use of parallel structure, which binds together the diverging power fantasies of each character, and illustrates that although the organic, telepathic parasite manipulates its victim by generating a delusional escapist narrative specifically personalized to satisfy, isolate, and immobilize a single victim, each of these fantasies has been created by the same xenomorph plant.

Comic books generally lack intellectual substance.

But in this case, the physical confrontation between Mongul and the Justice League serves to tangibly embody a spiritual critique of nostalgia, regret, contentment, grief, acceptance, and ambition.

Alan Moore utilized the techniques of metafiction in order to publish a classic, iconic Superman tale which speaks to the human condition on a fundamental level.

And by dissecting the negative consequences of fixating on escapist fantasies — an implicit commentary upon comic books and other escapist fiction which provide thrilling power fantasies to a mass audience — Alan Moore explores a deeper point, which is the relevance and resonance of motivational stories that we as humans tell ourselves, in order to provide structure, direction, and spiritual purpose to our own lives.

Our unconscious beliefs shape our families, careers, romances, rivalries, habits, moods, and obsessions.

Most people are gradually trapped by their fears or desires. They lose sight of the present reality, by dwelling too much on the missed opportunities of their past, or the potential rewards of their future.

A brilliant theme is seamlessly incorporated into a dramatic, kinetic showdown between cartoon villains and heroes.

This is the power of metafiction — it can surprise the audience, and say something beautiful, meaningful, and spiritual, by examining the universal religious desire in humanity which manifests in the pursuit of stories… the search for inspiration, meaning, and community which all humans share.

Life is confusing; all humans search for a meaningful life with the limited time available to us; stories provide us with examples, inspirations, and cautionary tales to provide accelerated models for how to live; the desire to be distracted, immersed, and entertained masks a deeper pursuit of spiritual truth; fiction provides a palatable delivery of difficult truths through allegory, symbolism, and metaphorical abstractions.

Metafiction is a shortcut, which leads to the heart of stories, and why we care about them.

Marty Phillips, Meta Realities and Dioramas:

What do I mean by a Meta-reality? I will do my best to define it briefly. A Meta-reality is a state of being in which abstracted spectacles and their accompanying recontextualized significance create a double existence where individuals experience actuality alongside a heightened, collectively perceived reality that has become unmoored. I will expand on this to better articulate my meaning. Meta-realities are heavily dependent on electronic communication, particularly audio-visual forms. This is due to the immediacy of images and new context through communication. Speed of information acquisition that nears that of sensory input can effectively replace sensory input in a manner that confuses actuality with a Meta-reality. If you can unlock your phone and see a video that alters expectations about your existence in the same amount of time that it takes to walk out your front door and see something occur on your street, then functionally the two experiences have equivalent significance in the human sensory matrix. This results in the Diorama Effect, where an alternate form of information environment is built around the observer. Actuality does not cease to exist, but two different realities progress schizophrenically side-by-side as they vie for control over consciousness.

Because Meta-reality is present alongside actuality, and the human mind craves stable and coherent experience environments, two follow-on effects follow. The first is Meta-reality Synthesis. This is the phenomenon where humans endeavor to force agreement between Meta-realities to resolve dissonance and restore credulity to the Diorama Effect. At times the attempts to force agreement are haphazard and quite obvious. One classic example is the combined racial reckoning and COVID-19 Meta-realities overlapping in 2020 when it was declared that, while COVID was extremely deadly and going out in public spaces was a sin equivalent to attempted murder, mass protest was acceptable because white supremacy is more dangerous than a virus. In fact, in many cases it was recontextualized in the sense that white supremacy was itself a virus. The COVID Meta-reality collided with the racial liberation Meta-reality. The diorama was hastily rebuilt with exposed drywall and unfinished windows, but it looked real enough for most people to shrug and go along. The mental distress of exiting the diorama into the contextless void of actuality is far more terrifying than momentary confusion.

The second follow on effect is Actuality Synthesis. This is far more insidious and consists of actuality being forced to bend to match the Diorama Effect. This typically lags the introduction of new meta-real spectacles, and can come in the form of concrete policies or collective notions about actuality. Evidence of this is most clear in persecution of those who reject widely shared dioramas. An example of this from geopolitics is the American derision toward France after the refusal to participate in the Iraq War in the years following 9/11. France rejected the Meta-reality of the post 9/11 world narrative created by the US government. The American people heaped scorn on them, but the French government was correct in their rejection of this version of reality. In our daily lives, we see countless examples of systems developed to punish Meta-reality rejection in the form of HR policies, unrelenting social pressure to conform with pop sociological narratives, and social media censorship.

How does one identify a Meta-reality and the Diorama Effect? It’s quite difficult now that we live in a world steeped in a virtual reality level of constant information barrage. One common attribute of Meta-realities is that they are often incongruent with their proposed effects and proposed solutions. Meta-realities often seek resolution. Through dissonant “solutions,” such as the Global War on Terror in the post 911 world, mass immigration in the post-colonial world, and the entire slacktivism movement of the twenty tens, we observe this incongruence. When you find these clear but weakly justified discrepancies, you have found a fault line between Meta-reality and actuality. It means that something else is going on, and a hastily designed story has been proliferated to obscure the complex truth.”

—Marty Phillips, Meta Realities and Dioramas

https://martyphillipswrites.wordpress.com/2023/11/04/meta-realities-and-dioramas-pt-1/

Marty Phillips, Meta Realities and Dioramas Revisited:

“I got back to thinking about these topics and decided to expand and edit this short essay after re-reading Philip K Dick’s The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch for a discussion with T.R. Hudson. I’d developed a simple outline of my concept of Meta-Realities and the Diorama Effect before revisiting the novel, but it occurs to me now that PKD’s concepts run parallel to my own thinking and our current collective social media delusions. In the book, despondent colonists sent unwillingly to desolate frontier worlds use a drug called Can-D in conjunction with dollhouse type dioramas to create facsimiles of an ideal earth and then experience living within them by psychically transmitting themselves into the doll characters within. The colonists want to escape their immediate misery and powerlessness by accepting a prefabricated existence where their lives have meaning. The communal nature of the drug allows them to work in congress to move around and undertake certain actions within the diorama. The majority takes over by sheer willpower and determines what they all do next.

…

When the titular Palmer Eldritch returns from the Prox System with a new drug called Chew-Z, the market for Can-D collapses because Chew-Z offers individual choice, or at least the illusion of it. The user can enter alternate realities and even future possible worlds. The catch is that these visions are all under the influence of Eldritch who can appear at will as any character. There’s an interesting parallel here between the dynamic of Can-D vs Chew-Z and the change from the world of television to that of the internet. Supposed freedom from pre-programmed narratives and the illusion of choice are hallmarks of the internet culture that derided boomer TV tropes while stumbling into a vortex of omnipresent surveillance and subtler psychological control. The diorama is still there, but millions of useful idiots have now volunteered in its construction and maintenance.”

—Marty Phillips, Meta Realities and Dioramas Revisited

Meta-Realities and Dioramas Revisited - by Marty Phillips (substack.com)

Another great piece. People spend thousands to get this kind of education

Now I have to go back and listen to all of your articles on writing. When I was a literature major, the critical theory lens was becoming the primary way we were instructed to analyze literature.

My kids are in school and every essay they write must be deconstructed through either a Marxist, Queer or Gender lens. My kids are not getting any other kind of instruction on writing and what makes for interesting writing … just told that all white male cannon authors (when they actually read them) were somehow queer and the papers they write are in class conflict and Marxist theory.

This is what I want. I will listen to your essays on writing and make sure they are able to think about writing in a better and more productive way.

So brilliant. Thank you.