Ray Bradbury, Zen in the Art of Writing:

“Remember that pianist who said that if he did not practice every day he would know, if he did not practice for two days, the critics would know, after three days, his audiences would know. A variation of this is true for writers.

You must stay drunk on writing so reality cannot destroy you. I have learned, on my journeys, that if I let a day go by without writing, I grow uneasy. Two days and I am in tremor. Three and I suspect lunacy. Four and I might as well be a hog, suffering the flux in a wallow. An hour's writing is tonic.

So that, in one way or another, is what this book is all about.

…

Work itself, after awhile, takes on a rhythm. The mechanical begins to fall away. The body begins to take over. The guard goes down. What happens then? RELAXATION. And then the men are happily following my last advice: DON'T THINK.

Which results in more relaxation and more unthinkingness and greater creativity.

…

You will have to write and put away or burn a lot of material before you are comfortable in this medium. You might as well start now and get the necessary work done. For I believe that eventually quantity will make for quality. How so?

A great surgeon dissects and re-dissects a thousand, ten thousand bodies, tissues, organs, preparing thus by quantity the time when quality will count — with a living creature under his knife. An athlete may run ten thousand miles in order to prepare for one hundred yards.

Quantity gives experience. From experience alone can quality come.

All arts, big and small, are the elimination of waste motion in favor of the concise declaration. The artist learns what to leave out.

The surgeon knows how to go directly to the source of trouble, how to avoid wasted time and complications. The athlete learns how to conserve power and apply it now here, now there, how to utilize this muscle, rather than that.

Is the writer different? I think not. His greatest art will often be what he does not say, what he leaves out, his ability to state simply with clear emotion, the way he wants to go. The artist must work so hard, so long, that a brain develops and lives, all of itself, in his fingers.

By work, by quantitative experience, man releases himself from obligation to anything but the task at hand. The artist must not think of the critical rewards or money he will get for painting pictures. He must think of beauty here in this brush ready to flow if he will release it. The surgeon must not think of his fee, but the life beating under his hands. The athlete must ignore the crowd and let his body run the race for him. The writer must let his fingers run out the story of his characters, who, being only human and full of strange dreams and obsessions, are only too glad to run.

Work then, hard work, prepares the way for the first stages of relaxation, when one begins to approach what Orwell might call Not Think! As in learning to typewrite, a day comes when the single letters a-s-d-f and j-k-1-; give way to a flow of words. So we should not look down on work nor look down on the forty-five out of fifty-two stories written in our first year as failures.

To fail is to give up. But you are in the midst of a moving process.

Nothing fails then. All goes on. Work is done. If good, you learn from it. If bad, you learn even more. Work done and behind you is a lesson to be studied. There is no failure unless one stops. Not to work is to cease, tighten up, become nervous and therefore destructive of the creative process.

…

So, you see, we are working not for work's sake, producing not for production's sake. If that were the case, you would be right in throwing up your hands in horror and turning away from me.

What we are trying to do is find a way to release the truth that lies in all of us.

Isn't it obvious by now that the more we talk of work, the closer we come to Relaxation. Tenseness results from not knowing or giving up trying to know. Work, giving us experience, results in new confidence and eventually in relaxation.

The type of dynamic relaxation again, as in sculpting, where the sculptor does not consciously have to tell his fingers what to do. The surgeon does not tell his scalpel what to do. Nor does the athlete advise his body. Suddenly, a natural rhythm is achieved. The body thinks for itself.

So again the three signs. Put them together any way you wish.

WORK.

RELAXATION.

DON'T THINK.

Once separated out. Now, all three together in a process. For if one works, one finally relaxes and stops thinking. True creation occurs then and only then. But work, without right thinking, is almost useless. I repeat myself, but, the writer who wants to tap the larger truth in himself must reject the temptations of Joyce or Camus or Tennessee Williams, as exhibited in the literary reviews. He must forget the money waiting for him in mass-circulation. He must ask himself, "What do I really think of the world, what do I love, fear, hate?" and begin to pour this on paper. Then, through the emotions, working steadily, over a long period of time, his writing will clarify; he will relax because he thinks right and he will think even righter because he relaxes. The two will become interchangeable. At last he will begin to see himself.

…

The time will come when your characters will write your stories for you, when your emotions, free of literary cant and commercial bias, will blast the page and tell the truth.

Remember: Plot is no more than footprints left in the snow after your characters have run by on their way to incredible destinations.

Plot is observed after the fact rather than before. It cannot precede action. It is the chart that remains when an action is through. That is all Plot ever should be.

It is human desire let run, running, and reaching a goal. It cannot be mechanical. It can only be dynamic.

So, stand aside, forget targets, let the characters, your fingers, body, blood, and heart do. Contemplate not your navel then, but your subconscious with what Wordsworth called "a wise passiveness."

—Ray Bradbury, Zen in the Art of Writing

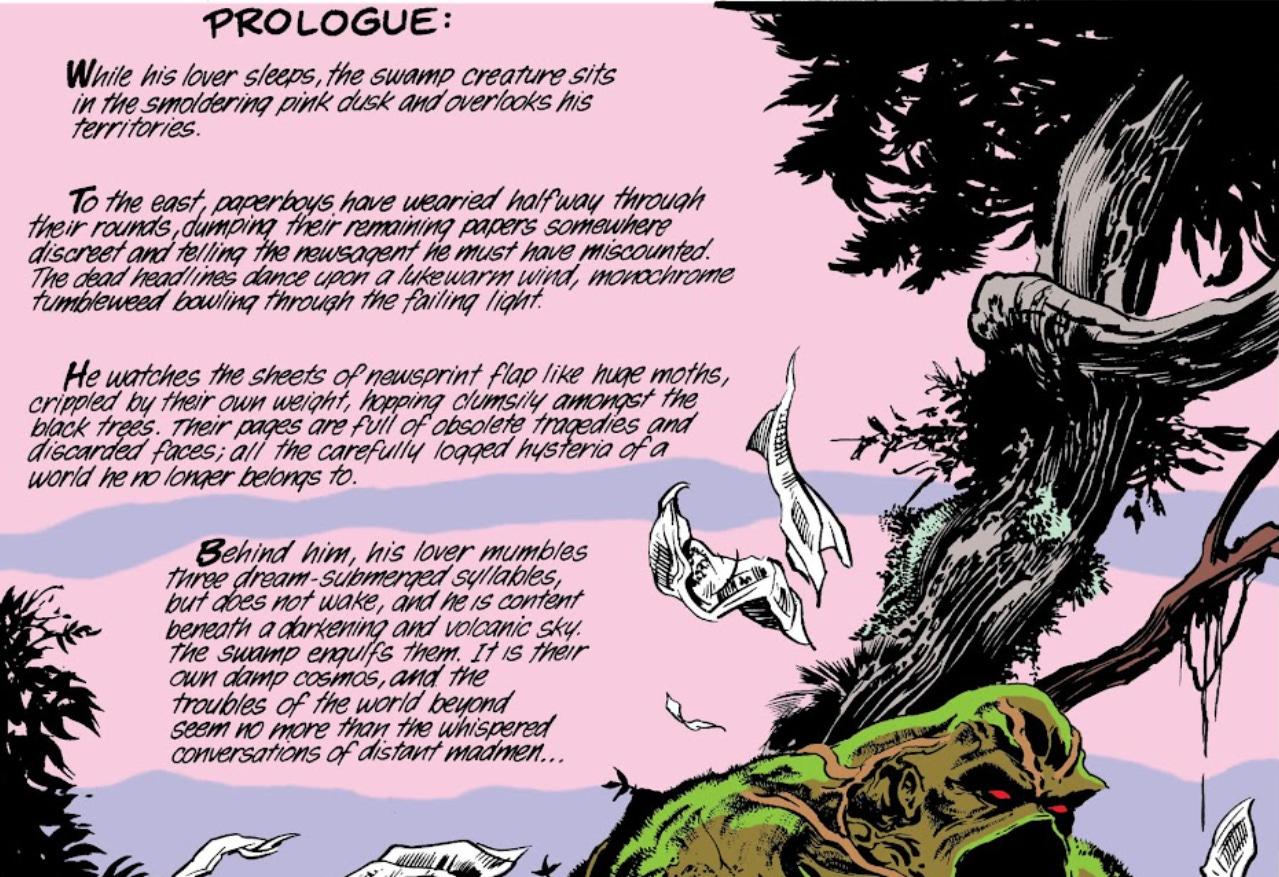

Consider the following passage, and take note of how gorgeous the prose is:

“While his lover sleeps, the swamp creature sits in the smoldering pink dust and overlooks his territories.

To the east, paperboys have wearied halfway through their rounds, dumping their remaining papers somewhere discreet and telling the newsagent he must have miscounted. The dead headlines dance upon a lukewarm wind, monochrome tumbleweed bowling through the failing light.

He watches the sheets of newsprint flap like huge moths, crippled by their own weight, hopping clumsily amongst the black trees. Their pages are full of obsolete tragedies and discarded faces; all the carefully logged hysteria of a world he no longer belongs to.

Behind him, his lover mumbles three dream-submerged syllables, but does not wake, and he is content beneath a darkening and volcanic sky. The swamp engulfs them. It is their own damp cosmos, and the troubles of the world beyond seem no more than the whispered conversations of distant madmen…”

—Alan Moore, Swamp Thing: Issue Thirty-Five

It’s a lovely opening.

Beauty overwhelms the audience.

Such a powerful scene makes a statement. Readers place their trust in the author, and allow themselves to be guided along by the unseen storyteller, immersed in dreams and nightmares, confident that the story will deliver a stylish opening, an exciting journey, and a satisfying emotional payoff by the end of the tale.

How does Alan Moore write this kind of stylish, evocative prose?

What is he doing on a mechanical, technical level?

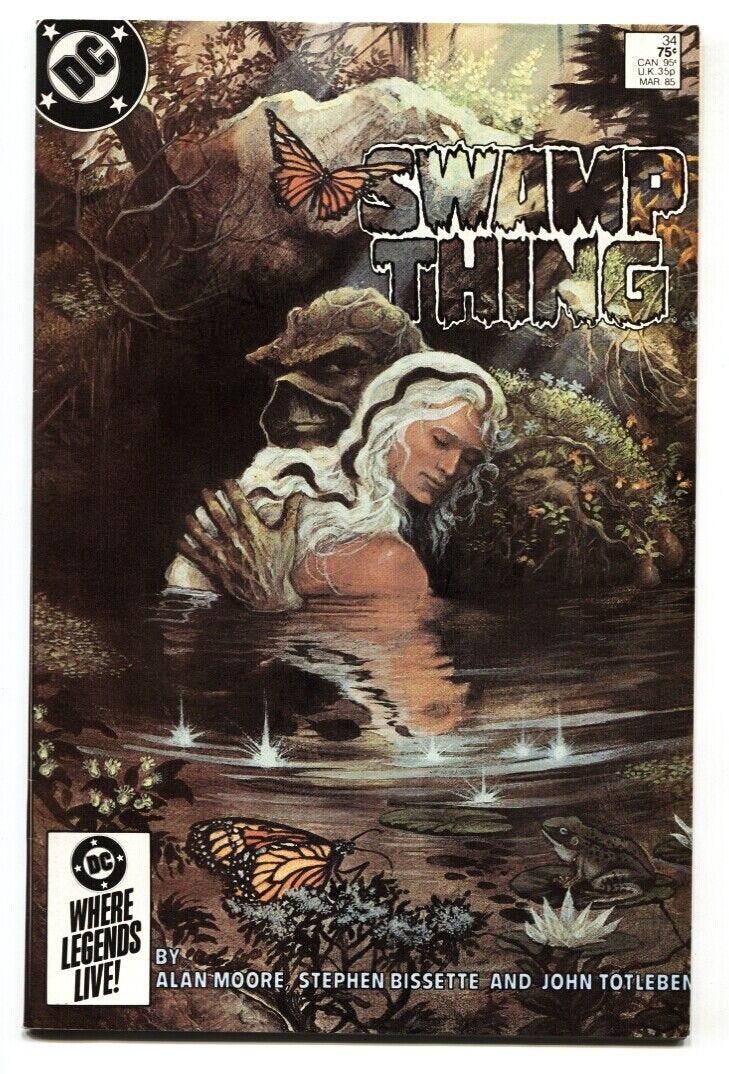

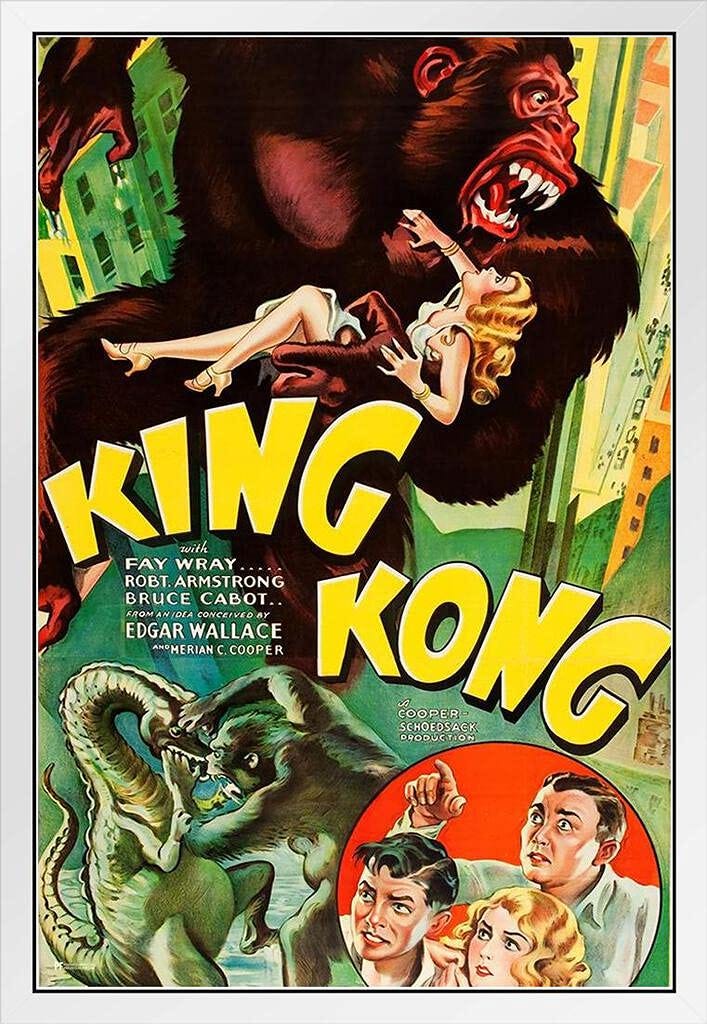

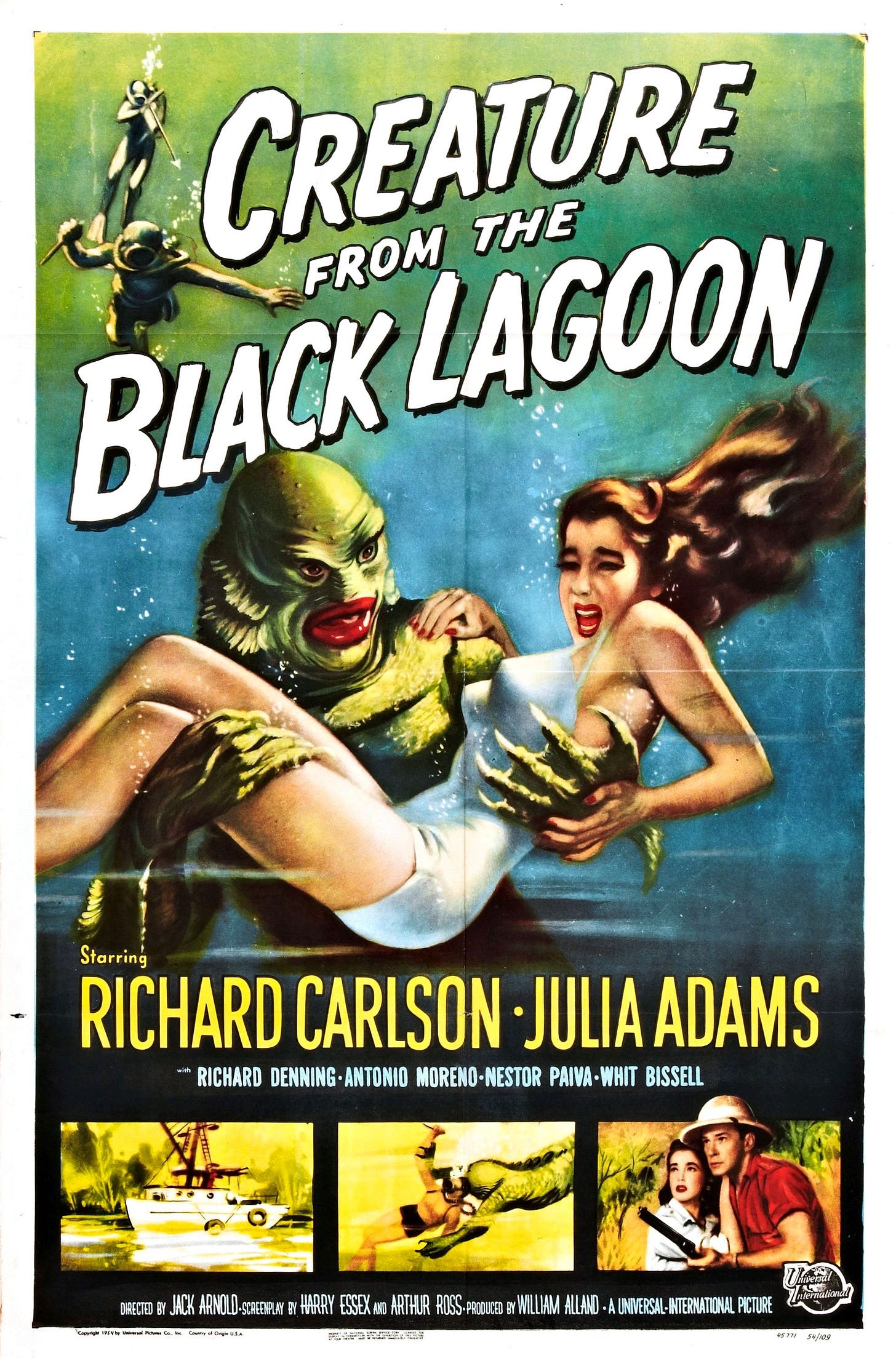

To look back on the four paragraphs displayed above, Alan Moore is juggling numerous, sophisticated tricks. The content is simple. Swamp Thing is a horror story with more or less the same emotional nucleus as King Kong, Frankenstein, The Creature from the Black Lagoon, The Phantom of the Opera, or The Hunchback of Notre Dame. These are all archetypal reflections of the classical fairy tale, Beauty and the Beast.

The plot is fluid, but the emotional struggle of a lonely, sexually-frustrated monster remains familiar.

“This ghastly laughter gives occasion, moreover, for the one strain of tenderness running through the web of this unpleasant story: the love of the blind girl Dea, for the monster. It is a most benignant providence that thus harmoniously brings together these two misfortunes; it is one of those compensations, one of those afterthoughts of a relenting destiny, that reconcile us from time to time to the evil that is in the world; the atmosphere of the book is purified by the presence of this pathetic love; it seems to be above the story somehow, and not of it, as the full moon over the night of some foul and feverish city.”

—Robert Louis Stevenson, Familiar Studies of Men and Books:

“Chapter One: Victor Hugo’s Romances”

Andrew Lloyd Webber, The Phantom of the Opera: "Past the Point of No Return":

[PHANTOM:]

“Past the point of no return

No backward glances

The games we played till now are at an end

Past all thought of “if” or “when”

No use resisting

Abandon thought and let the dream descend

What raging fire shall flood the soul?

What rich desire unlocks its door?

What sweet seduction lies before us?

…

[CHRISTINE:]

You have brought me

To that moment when words run dry

To that moment when speech disappears

Into silence

Silence

I have come here

Hardly knowing the reason why

In my mind, I've already imagined

Our bodies entwining

Defenseless and silent

Now I am here with you

No second thoughtsI've decided

Decided

Past the point of no return

No going back now

Our passion-play has now, at last, begun

Past all thought of right or wrong

One final question

How long should we two wait, before we're one?When will the blood begin to race?

The sleeping bud burst into bloom?

When will the flames, at last, consume us?

[PHANTOM:]

Say you'll share with me

One love, one lifetime

Lead me, save me from my solitude.”

—Andrew Lloyd Webber, The Phantom of the Opera: "Past the Point of No Return"

A grotesque outsider lurks along the fringes of the social order, and gravitates upon a beautiful, innocent woman as a target of his lust. But his sexual conquest is a deeply neurotic, guilt-obsessed pursuit. Instead of a normal, commonplace seduction, the monster sets himself up for failure by projecting all of his insecurities and inadequacies onto the woman he desires. In his mind, she is no longer a regular woman. He reinterprets her existence as a symbolic manifestation of a social, psychological, and spiritual solution to everything that bothers him about his life. Sex alone will not satisfy him. He is pursuing something more abstract, and more futile. A doomed fantasy.

He has the strength and titanic bulk of an overpowering brute, but the impractical desires of a frustrated romantic, and incrementally regresses into an emotional cripple, sedated by self-loathing.

And for this reason, the monster always kidnaps the woman of his dreams, carries his victim into a moss-encrusted cavern… a ruined castle… a tangled forest… a disorienting, spider-haunted labyrinth — but never rapes her, and in fact is frightened of sharing a prolonged conversation with his romanticized ingenue.

You will notice that the classic Frankenstein archetype, the Persecuted Outsider, the Blackpilled Incel chooses to stalk the woman of his dreams, ambushes and overpowers her, drags her into the bushes, lifts her into his secluded hideout, shackles his dream girl to iron chains — and hurriedly limps off to the other side of the cave, so that he can avoid talking to her.

Mission accomplished.

Romance 101: Kidnap your ideal pageant queen, then ignore her, and brood in the distance, reflecting upon the unfairness of life.

But in a strange fashion, this reveals the monster’s real goal.

Nobody else can take his girl, when she is locked up like Rapunzel. But he protects himself from sexual rejection by avoiding casual interactions with the woman of his dreams. And more importantly, he manufactures and preserves the illusion he has constructed in his mind, then projected onto an exquisite (yet imperfect) woman. Staring at an idealized woman is enjoyable. In symbolic terms, she represents a higher spiritual purpose, and the hope that society might someday approve and validate his existence. But the lonely monster doesn’t want to take the risk of talking to her, because she could repudiate his affection. Worse, she is almost guaranteed to disappoint the fantasy he has manufactured in his own mind.

There’s a certain level of comedy here.

A pathetic, self-defeating cycle.

Suicide by blonde.

The lonely monster is unable to accept himself, and instead seeks to skip the process of self-actualization by reliance upon an external symbolic authority to validate the meaning of his life. Searching for an outward source of validation and encouragement, the Persecuted Outsider, the Blackpilled Incel offloads his own weakness onto a beautiful stranger, with the hope that he can achieve atonement, obtain spiritual fulfillment, and find personal completion in the arms of a beautiful woman. Instead, the Frankenstein monster is usually hunted down by a mob of villagers wielding torches and pitchforks.

And the real solution of self-acceptance was always there… waiting for him to simply forgive himself, accept his circumstances, and stop chasing an impossible dream. To quit feeling sorry for himself. Self-pity feels good, but it’s an emotional dead end. Everyone else could see him for what he already was — huge, and dangerous. Capable of terrible destruction… and astonishing construction.

Presented in these terms, the archetype of Beauty and the Beast seems a little ridiculous. Borderline contemptible. Some kind of craven personality disorder.

These posters reflect an insecure masculine psychology — the monster is portrayed as hideous and repulsive, juxtaposed against a woman who is voluptuous, vulnerable, and virginal. Instead of assuming the sale, this monster starts out with the expectation that he will be rejected, that he deserves to be rejected, that he is a worthless loser, and that no matter how much he tries, he will always be a worthless loser.

But it’s not as bad as it seems.

The Frankenstein monster, the Swamp Thing, the hideously-scarred hunchback is symbolic. He is an exaggerated depiction of a universal fear, which both men and women share. And he is portrayed in an inhuman fashion to emotionally and intellectually distance the audience from a message that provokes intense, subconscious discomfort. The dripping fungus of the Swamp Thing, crawling with insects, has been safely abstracted into an unrecognizable parody of a basic, elemental insecurity that to some extent impacts everyone.

Everyone feels lonely sometimes, or misunderstood.

Everyone feels like an outsider, separated from the rest of the group, exiled to the fringes of a conversation.

At the core, Swamp Thing represents a pursuit of unconditional love.

And an unspoken fear that unconditional love is impossible, it doesn’t exist, and that the best anyone can hope for is a flimsy, temporary substitute of transactional loyalty.

Or, as Gillian Flynn wrote in Gone Girl:

“I was told love should be unconditional. That’s the rule, everyone says so. But if love has no boundaries, no limits, no conditions, why should anyone try to do the right thing ever? If I know I am loved no matter what, where is the challenge? I am supposed to love Nick despite all his shortcomings. And Nick is supposed to love me despite my quirks. But clearly, neither of us does. It makes me think that everyone is very wrong, that love should have many conditions. Love should require both partners to be their very best at all times. Unconditional love is an undisciplined love, and as we all have seen, undisciplined love is disastrous.

You can read more about my thoughts on love in Amazing. Out soon!

But first: motherhood. The due date is tomorrow. Tomorrow happens to be our anniversary. Year six. Iron. I thought about giving Nick a nice pair of handcuffs, but he may not find that funny yet. It’s so strange to think: A year ago today, I was undoing my husband. Now I am almost done reassembling him.

Nick has spent all his free time these past months slathering my belly with cocoa butter and running out for pickles and rubbing my feet, and all the things good fathers-to-be are supposed to do. Doting on me. He is learning to love me unconditionally, under all my conditions. I think we are finally on our way to happiness. I have finally figured it out.

We are on the eve of becoming the world’s best, brightest nuclear family.

We just need to sustain it. Nick doesn’t have it down perfect. This morning he was stroking my hair and asking what else he could do for me, and I said: ‘My gosh, Nick, why are you so wonderful to me?’

He was supposed to say: You deserve it. I love you.

But he said, ‘Because I feel sorry for you.’

‘Why?’

‘Because every morning you have to wake up and be you.’

I really, truly wish he hadn’t said that. I keep thinking about it. I can’t stop. I don’t have anything else to add. I just wanted to make sure I had the last word. I think I’ve earned that.”

—Gillian Flynn, Gone Girl

A story like Swamp Thing seems to accept that unconditional love will never be a collective phenomenon, but perhaps the rare, individual miracle can occur — between one man and one woman, joined in a passionate, sensual relationship, perhaps euphoria and affection and admiration can transcend the transactional nature of ordinary relationships. And maybe love can elevate that connection to a close approximation of complete acceptance, affirmation, and encouragement.

It’s reminiscent of the aphorism by novelist John Gardner, “Every marriage is a little civilization, and the end of a marriage is the fall of the civilization.”

The pessimistic view of this debate would be expressed by Tennessee Williams, "We are all sentenced to solitary confinement inside our own skins, for life."

Or, as Stephen King has written:

“I believe that we are all ultimately alone and that any deep and lasting human contact is nothing more nor less than a necessary illusion — but at least the feelings which we think of as "positive" and "constructive" are a reaching-out, an effort to make contact and establish some sort of communication. Feelings of love and kindness, the ability to care and empathize, are all we know of the light. They are efforts to link and integrate; they are the emotions which brings us together, if not in fact then at least in a comforting illusion that makes the burden of mortality a little easier to bear.

Horror, terror, fear, panic: these are the emotions which drive wedges between us, split us off from the crowd, and make us alone. It is paradoxical that feelings and emotions we associate with the "mob instinct" should do this, but crowds are lonely places to be, we're told, a fellowship with no love in it.

The melodies of the horror tale are simple and repetitive, and they are melodies of disestablishment and disintegration… but another paradox is that the ritual outletting of these emotions seems to bring things back to a more stable and constructive state again.

…

One of the questions that frequently comes up, asked by people who have grasped the paradox (but perhaps not fully articulated it in their own minds) is: Why do you want to make up horrible things when there is so much real horror in the world? The answer seems to be that we make up horrors to help us cope with the real ones. With the endless inventiveness of humankind, we grasp the very elements which are so divisive and destructive and try to turn them into tools — to dismantle themselves.”

—Stephen King, Danse Macabre

Personally, I prefer the philosophy of Winnie the Pooh, that “A hug is always the right size,” and "Any day spent with you is my favorite day. So, today is my new favorite day,” and “If you live to be a hundred, I hope I live to be a hundred minus one day, so that I never have to live a day without you.”

If we reexamine the four paragraphs above, written by Alan Moore, you can see how these themes are subtly communicated, by emphasizing how the Swamp Thing and his lover have distanced themselves from human civilization…

Swamp Thing is an outsider.

These sentences express a universal sense of alienation:

“Their pages are full of obsolete tragedies and discarded faces; all the carefully logged hysteria of a world he no longer belongs to.

Behind him, his lover mumbles three dream-submerged syllables, but does not wake, and he is content beneath a darkening and volcanic sky. The swamp engulfs them. It is their own damp cosmos, and the troubles of the world beyond seem no more than the whispered conversations of distant madmen…”

—Alan Moore, Swamp Thing: Issue Thirty-Five

Simple emotions carry tremendous impact.

Alan Moore writes beautiful prose, embellished with clever stylistic tricks, but these tricks are transformed into something much bigger, much stronger, far more beautiful because they are delivering a message burdened with incredible substance.

Flamboyance captures attention. Authenticity establishes trust. And communicating an actionable insight rewards the audience enough to merit recurring subscriptions, or views, or attention, or however we want to quantify an ongoing relationship between an author and an audience.

Let’s turn our attention to the mechanical construction of prose.

The prologue to Swamp Thing: Issue Thirty Five is clever and engrossing on many levels, in many respects, but two sentences stand out to me in particular. They reflect a signature prose technique demonstrated by Alan Moore, throughout his career. And these are:

“The dead headlines dance upon a lukewarm wind, monochrome tumbleweed bowling through the failing light.

He watches the sheets of newsprint flap like huge moths, crippled by their own weight, hopping clumsily amongst the black trees.”

—Alan Moore, Swamp Thing: Issue Thirty-Five

What a strange choice of phrasing.

How does Alan Moore sculpt a description of a mundane scene, into such a baroque and unexpected form?

Nobody else would talk about the weekly distribution of newspapers in such eccentric, idiosyncratic language.

How can we learn to write like this? And why would we want to imitate this language? What does this description accomplish, in narrative terms?

It’s a signature technique.

A distinct, recognizable pattern.

Elsewhere, Alan Moore has written similar descriptions:

“Sunset over Houma. The rains have stopped. Clouds like plugs of bloodied cotton wool dab ineffectually at the slashed wrists of the sky.”

—Alan Moore, Swamp Thing Issue Twenty-Two

“It’s raining in Washington tonight. Plump, warm summer rain that covers the sidewalk with leopard spots. Downtown, elderly ladies carry their houseplants out to set them on the fire-escapes, as if they were infirm relatives or boy kings. I like that.”

—Alan Moore, Swamp Thing Issue Twenty-One: “The Anatomy Lesson”

“The soil is curdled. And all that grows… grows wrong. In a skin of black cinder, puddles reflect fire… red and wet and glistening like sores. The song of stillborn birds echoes… through the deformed metal trees. There is a rattle in the throat of the wind. And I am alone. Alone in deathtown.”

—Alan Moore, Swamp Thing Issue Thirty-Five

“Like trapped flies, the low buzz of whispered laughter.”

—Alan Moore, Swamp Thing

“Your molecules spin like flywheels in the vast, soft clockwork of the wilderness.”

—Alan Moore, Swamp Thing

“He is propelled, a blazing stringless puppet stumbling through the flames like some Catholic martyr.”

—Alan Moore, Swamp Thing

Even some of his friends, and fans, have written similar descriptions in imitation of Alan Moore’s linguistic patterns, to pay tribute to his aesthetic legacy:

“It seems like a long time ago — swollen torrents of words have roared under many bridges; oceans of exotic imagery have swirled and risen; the shapes of continents have changed. Strange, how one’s life passes.”

—Jamie Delano, Saga of the Swamp Thing: Book Two “Introduction”

“I found the neighborhood horrible. A long row of houses which stretched as far as the eye could see like a long spinal chord of the fossil of a brachiosaurus disappearing around the curve of the horizon. These kind of panoramic monstrosities do not exist where I come from. They cannot even be compared with Hell, because there you imagine things to be in perpetual motion and constantly changing like inside the crater of a volcano.”

—Alessandro Bilotta, Alan Moore: Portrait of an Extraordinary Gentleman

What’s the common pattern here?

What’s the underlying technique?

It’s the same combination of rhetorical devices, crammed together, time and time again.

In each sentence, we find that an ordinary and unremarkable scene is being described to the audience. Examples include the newspaper mail route, a sunset, a rainstorm during which old women carry their potted plants outside, the dull ambient noise of a crowd. Most of these incidents are banal. Forgettable occurrences. Alan Moore’s prose transforms these pedestrian, routine interactions into a peculiar, outlandish spectacle.

Some of the sentences are more stripped-down than the rest, and skip the full onslaught of stylistic mechanisms. But the rest conform to a formula:

1.) The use of both adjectives and verbs, which are placed to modify a noun.

2.) The noun is described with either a metaphor or a simile, in order to take a familiar concept and transport it into an unfamiliar context, which draws the audience’s attention to the sensory experience, or the power dynamic being discussed.

3.) Vivid imagery, which sometimes includes the use of colors.

4.) Finally, these descriptions will be electrified with intense sensations, OR characterized by a philosophical orientation, OR cast in terms of a frenzied emotional valence. To restate this in plain English, Alan Moore starts by identifying a background detail in the world of the story. He describes it, and then he goes a step further and tells the audience why the details are important; what is relevant about the scene — either in terms of sensation, philosophy, or emotion.

All of this happens in one single sentence. It’s very busy.

Various techniques are crammed together, overloading the prose, deluging the audience with an excessive compilation of rhetorical effects.

Alan Moore takes a familiar event, interaction, or idea — then recontextualizes it, which spotlights the actual strangeness of the familiar world by emotionally reframing the subject, object, trend, or interaction with eccentric and provocative language.

This kind of flowery language should be used sparingly, and only to highlight key beats in a story.

Very dense clusters of imagery can be inserted, sprinkled into occasional prose when you want to give it a kick, to emphasize and amplify a certain image or scene. This onslaught of rhetorical devices empowers a storyteller to take something ordinary and make it feel extraordinary, make it feel special, find the beauty in it.

There’s a method to this madness.

And it is, indeed, madness.

Alan Moore explains why he enjoys overloading the audience’s focus with dense, simultaneous narrative threads that intercut, overlap, and drown each other out with a confused, Dionysian cacophony of disorganized, manic enthusiasm:

Alan Moore, The Dark Side of the Moore: "An Interview Conducted by Omar Martini":

“I found it really interesting and the particular thing was that at every reading I found some pieces… I understood something more than on each previous reading. Well, all the pieces that we do we try to make them very dense, they generally deal with large subjects and we've got generally about an hour to do them all, without them seeming rushed, and then they've got a kind of structure to them so that they would build nicely in the audience's mind and consequently we've got to get immense amount of detail into these things.

I think that actually at the performances they can be a little overwhelming.

The audience can’t possibly... by the time they've paused to fully appreciate one line, they've missed the next two. But that’s fine.

I quite like the idea of overwhelming the audience’s normal critical faculties.

You have this densely written language in one stream, then you've got very complex music in one other stream, you've got theatrics, maybe a fire breather... you've got synchronised psychedelic film collage... this sort of multimedia approach again, goes very much back to my Arts Lab days. I’m starting to appreciate it more because it almost... When the mind of the audience is taking in more information every second than it can handle, the effect of all these things become something like... perhaps psychedelic drugs, a kind of fugue state, where there are too many vectors of information occurring at once.

So the mind tends just to give up and be carried along by the flow. Even if they're not taking in the meaning of every word, every sentence, I think that they are certainly soaking up all of the emotion and the general feeling of the thing. So I’m not too worried if they can’t get it all at the first hearing.”

—Alan Moore, The Dark Side of the Moore: "An Interview Conducted by Omar Martini"

Alan Moore stampedes the audience.

He creates intentional chaos and disorder, by displaying contradictory focal points, so that the audience doesn’t know which details they are supposed to concentrate on. And then he scatters riddles, puzzles, and Easter Eggs amid the chaos, so that intelligent readers will have the pleasure of returning to his stories over and over again, each time rediscovering some beautiful detail overlooked during previous reading sessions. There is an immense intellectual pleasure in this kind of archaeological excavation of a generous text which continues to surrender its treasures to the patient, meticulous examiner. There is a scope, and depth, which other manuscripts lack.

Most stories have nothing happening beneath the surface. Even the surface of the story is boring and predictable, without the counterpoint of subtext, contradictions, and omissions boiling beneath the calm facade of a neatly-structured world. Complex, dense stories resemble a seething, pent-up volcano which might erupt at any moment. That threat of PURE ANNIHILATION is strobing… writhing… thrashing… along the peripheral edge of the audience’s subconscious. Readers can sense that at any moment, an unseen, predatory element which stalks and hungers and crouches beyond view — a dangerous, prehistoric leopard escaped from the distant mist of antediluvian epochs — a fanged, man-eating carnivore is lurking in the cold, quiet stillness of the night, something terrible and implacable which is eager to pounce from the shadows of the jungle.

Something atavistic. Something ferocious.

Something insatiable.

And through this chaos, amid this carefully-constructed hurricane of mind games and rhetorical devices, the audience loses logic. They are overwhelmed by the frenetic, manic energy of the performance. They are swamped by the Swamp Thing.

Emotion takes over.

A childish sense of wonder, and awe.

Without a doubt, these lessons can be incorporated into your own stories, your own performances.

Personally, I prefer a terse, efficient, stripped-down style which fluidly communicates a point, and then glides along to the next part of a story, without pausing on an unimportant detail. There is the risk of overwriting a scene, of descending into absurdity by attempting to manufacture a sense of drama when nothing interesting is happening.

But it’s useful to know that these options are available, and there are solid alternatives to simply writing an efficient, cogent narrative.

Prose can be gorgeous, and it deserves meticulous cultivation.

Alan Moore, Alan Moore’s Writing for Comics: Volume One:

“We seek to arrive at the correct stream of both verbal, and visual narrative.

By verbal narrative, I mean the exact choice of words, and the flow of language that will take the reader through the story upon one level, and the precise flow of imagery that will take him or her through the book upon another level.

The fine craft of wordsmithing is important in that clumsy or boring or lifeless language stands a high chance of distracting the reader from the story that you’re trying to tell. You first learn how to use the words to the best of your ability, once more applying real thought to the processes involved. What, for example, separates an interesting sentence from a dull one? It’s not the subject matter.. A good writer can write about the most mundane object in the world and make it interesting.

It’s something in the arrangement of words that brings the whole structure alive with meaning, and makes a powerful impression upon the reader — not in the content of those words.

By looking at sentences in the works of others that have appealed to you — whether in a poem, or a novel, or a comic — it’s possible to see certain patterns which follow similar, basic principles to phenomena that we’ve discussed earlier: The element of surprise is very often the most appealing thing about a sentence… the surprising use of a word, or the surprising juxtaposition of two interesting concepts.

Using an example that I personally quite liked but which most people seem to find an example of my overwriting at its worst, there was a line in an early Swamp Thing about clouds like plugs of bloodied cotton wool dabbing uselessly at the slashed wrists of the sky. That was a description of a sunset. The intention was to describe a thing of unquestioned beauty in very ugly, sordid, and depressing terms. I found the juxtaposition of the two sensations stimulating and entertaining, but apparently for a lot of people it crossed over the line into self-parody, which smacks of bad judgment upon my part, but remains something I shall probably do again and again for the rest of my career.

Creating a single story requires that you make thousands and thousands of tiny creative decisions on the basis of whatever theories you hold dear, and the application of large measures of intuition. Much as I would it were otherwise, nobody gets it right all the time, and if you have made a mistake the only thing you can do is analyze it, see if you agree with your critics, and respond accordingly.

Adverse reaction aside, I still believe that the principle of surprise behind the sentence referred to above is sound, even if the actual execution left something to be desired.

Along with the surprise content of the language, and the concepts in each sentence, there is verbal rhythm to consider. A sentence overloaded with long, multi-syllable words, for example, would probably have a very jerky and unsatisfactory stumbling kind of rhythm in the reader’s head as he or she reads the line, and even more so if they attempt to read it aloud.

Be conscious of the rhythm in your writing, and of the effect that it has on the tone of your narrative. Long, flowing sentences with lots of lush imagery will have one effect. Short, sparse sentences delivered in machine-gun fashion will have another.

Sometimes, repeating a phrase of a word will give a sequence a rhythm almost like music, where various musical phrases are repeated throughout a piece to lend it structure. Each word-rhythm has its own attributes, and there is an infinite number of different rhythms to be discovered by someone with enough imagination.”

—Alan Moore, Alan Moore’s Writing for Comics: Volume One

“But I'm a creep, I'm a weirdo. What the hell am I doin' here? I don't belong here.” - Frankenstein

I’m struck by the phrase “crippled by their own weight” in the Swamp Thing’s passage. The symbolism is strong here, in addition to the imagery. This stands for the weight of the beast, whose tremendous bulk also carries the agony of exile from society. He is an (emotional/romantic) cripple despite his immense power because he does not dare reach out to connect with another. I’ve loved Alan Moore’s characters like Rorschach in “The Watchmen”and his sense of the outsider peering into a society that he both despises but desperately wishes to join. Tremendous work.