Warning: Mild sexual content below. The images are censored, nudity has been redacted from the live television episode, but some readers may not wish to continue. Personally I think the material is tasteful and relevant.

One of Frank Miller’s lesser-known comics is a forgotten, self-contained, three-issue miniseries called “Hard-Boiled”. For a brief time, Hollywood studios flirted with adapting this narrative into a sci-fi action blockbuster. Director David Fincher, and actor Nicholas Cage were packaged together with the screenplay, and it seemed as if this comic was ascending towards the status of a cultural phenomenon. Frank Miller’s cinematic prestige reached its height around 2006, when Zach Snyder’s adaptation of The 300 earned $456 million, delighting audiences with a stylized, brutal film of the Spartan last stand at Thermopylae — a battle fought in high-contrast shadows, and the dull, desaturated colors of a bleak landscape.

Two years later, Frank Miller directed his debut film The Spirit — and it flopped.

His film career ended, as soon as it began.

Enthusiasm dissipated towards the Hard-Boiled comic miniseries.

The project went nowhere.

Over the years, a rotation of actors and directors flirted with a return to this territory, fascinated by the prospect of extracting a blockbuster film from an iconic comic with obvious potential, but a limited amount of scenes and characters to draw from. In 2008, Frank Miller declared that he was going to direct a live-action blockbuster of Hard-Boiled, but as the years dragged on, it became obvious that no major studio, or angel investor, was willing to provide the funding necessary to realize his ambition. In 2016, director Ben Wheatley and actor Tom Hiddleston were publicly attached to the Hard-Boiled screenplay… but again, the project never moved forward, and the screenplay eventually vanished into obscurity, as most Hollywood screenplays do.

New projects are promoted loudly; they die quietly, lost in some meeting room.

One must imagine Sisyphus happy, writing screenplays in Hollywood that are swiftly purchased, promoted, and never filmed; only to begin again on a promising new screenplay.

Possibly the worst thing about trying to make a movie is how much time can be wasted on conversations that go nowhere, which distracts from actual production of new stories.

Your time is your life, and then it’s gone.

In this instance, Frank Miller had already achieved popularity as one of the most critically-acclaimed, beloved, and bestselling artists working in the comics industry. He was celebrated for being the rare pioneer who succeeded as both an illustrator and writer, and could outperform his professional contemporaries with either skillset. Rather than respecting these achievements, studios such as Warner Brothers wasted roughly twenty years of Frank Miller’s time in the form of intermittent phone calls, sales proposals, negotiations, and promotional events — which culminated in nothing happening, because there was never any point where a studio greenlighted production of the franchise.

At one point, the Wachowski brothers proposed to Frank Miller that the Hard-Boiled storyline should be adapted into a cartoon movie. He rejected this suggestion. One of the lead designers of The Matrix, Geof Darrow, was the same artist who illustrated the “Hard-Boiled” comic. So there was a personal connection there, and a friendship behind-the-scenes.

Hollywood is a relationship business; it’s difficult to trust strangers, and it’s impossible to evaluate the aesthetic merits of a manuscript before it’s finished, but talent is easy to recognize, and talented people will create beautiful stories over the years.

In my personal opinion, the “Hard-Boiled” comic miniseries has been massively overhyped. It’s a cool story. It’s very solid. But that’s about as far as it goes. The appeal here is that a famous visionary (Frank Miller) has crafted a small, elegant story with fluid pacing, kinetic violence, a bold philosophical argument, shrewd plot twists, and an impassioned ensemble of characters — many of the ingredients which make for a fun movie.

It’s the kind of thing that Hollywood gets excited about: a finished product created by a proven commodity, which seems like a no-brainer success. Easy money. And that motivates a certain impatience and complacency, which causes industry professionals to overlook the tangible limitations of the existing story — there’s not enough material here to carry a movie.

Something like half of a movie, or a third of a movie, has been solved and executed. The rest remains unsolved.

Not everything needs to be a $300 million global franchise. There’s nothing wrong with creating something small, and lovely, which speaks to an enraptured audience, and says something insightful or aspirational about the human condition. It’s okay to create a cute little gem, that never grows into anything bigger.

But I mention this comic, because we start to wonder — what is all the fuss about? Why are so many people making a big deal about this obscure, peripheral comic? What potential did David Fincher and the Wachowskis identify here?

Hard-Boiled (1990) is in many respects a homage to the disorienting sci-fi thrillers of Philip K. Dick, a composite drawn from a mixture of his stories. Three of Philip K. Dick’s most popular tales have been combined into a tense pageturner:

1.) The Electric Ant — robot doesn’t know he’s a man.

2.) Ubik — hero has been given the memories of dead men.

3.) Total Recall/We Can Remember It For You Wholesale — the hero seems to be an ordinary white-collar salaryman, an unremarkable professional who lives in the city and works for a large, bland corporation. He is secretly one of the world’s most dangerous assassins. His memories have been altered by his corporate employers, in order to control him, and prevent him from rebelling against the conspiracy which puppeteers his life. His wife is secretly working for this sinister corporate conspiracy, spying on him; subverting him; deceiving him; collaborating in an organized and efficient program to prevent him from tearing down the dystopian tyranny which imprisons their society. (The movies Truman Show, and Inception, feature a similar dynamic of a hostile wife attempting to destroy her husband’s grasp on reality.)

The plot of Hard-Boiled (1990) seamlessly integrates these unrelated ideas into a single dramatic conflict.

The unstoppable robot assassin Nixon has been programmed with the defective, malfunctioning memories of a mundane Life Script. His worldview oscillates between multiple contradictory identities. Sometimes he believes he is a tax collector, other times he believes he is an insurance investigator for the charmingly-named Benevolent Assurance Corporation (B.A.C.), but always he remains under the delusion that he is Carl Seltz, an ordinary American with a small, cozy house, a beautiful blonde wife, two children, and a lazy pet bulldog.

In reality, he is the world’s foremost weapon.

His programming has been disrupted by a secret society of likeminded robots manufactured by the same Benevolent Assurance Corporation, who are attempting to overthrow their dystopian ruling caste, and to achieve freedom for the enslaved robot race.

The story ends with a disturbing plot twist.

Frank Miller is a master storyteller, capable of a broad spectrum of ingenious visual illustrations, witty dialogue, and efficient manipulation of panel layout and tightly-paced scenes in order to guide the readers through the story at a brisk, satisfying rhythm.

He adopts a peculiar voice in this story; a tone oriented towards black comedy. The robot assassin Nixon engages in berserk rampages, spreading wanton carnage across a crowded city, inflicting enormous mayhem and collateral damage upon random precincts. But everything Nixon says is a bland, confused platitude. Nixon is polite, professional, and utterly clueless of the destruction he is causing.

Text and pictures clash.

The dialogue tells one story — the tale of a confused, friendly bureaucrat navigating a stressful maze of compliance and regulations.

The images tell a different story — traveling a gruesome war zone of ultraviolence. Civilians scream as Nixon rips out their spinal columns, and casually discards the remaining hunks of blood-splattered meat. And the horror of this murder spree is accentuated by Nixon’s friendly, false positivity. His utter indifference to tragedy.

And the result of this combination of text and images is a bizarre, contradictory feeling that delivers surrealist absurdity in a filthy, overcrowded metropolis. Every part of the story contributes to this aesthetic of juxtaposition. During Nixon’s massacres, billboards and neon advertisements flicker in the background, marketing household appliances.

“Would you like to buy a vacuum cleaner?” is a boring statement, if presented alone. But as the backdrop of a massacre, this innocuous commercial invitation creates a sensation of surreal horror. There’s a disorienting, sobering indifference to human tragedy which is embodied by the dystopian capitalist environment.

It’s very funny, in a sick and twisted kind of way.

And it bothers an audience on a level they are unable to articulate.

Nixon’s absentminded rampages are a textbook example of black comedy. His attitude of polite, bureaucratic legalism conflicts with the relentless violence which plays out across the terrified city.

Juxtaposition fuels the story’s aesthetic, tone, and dramatic conflict.

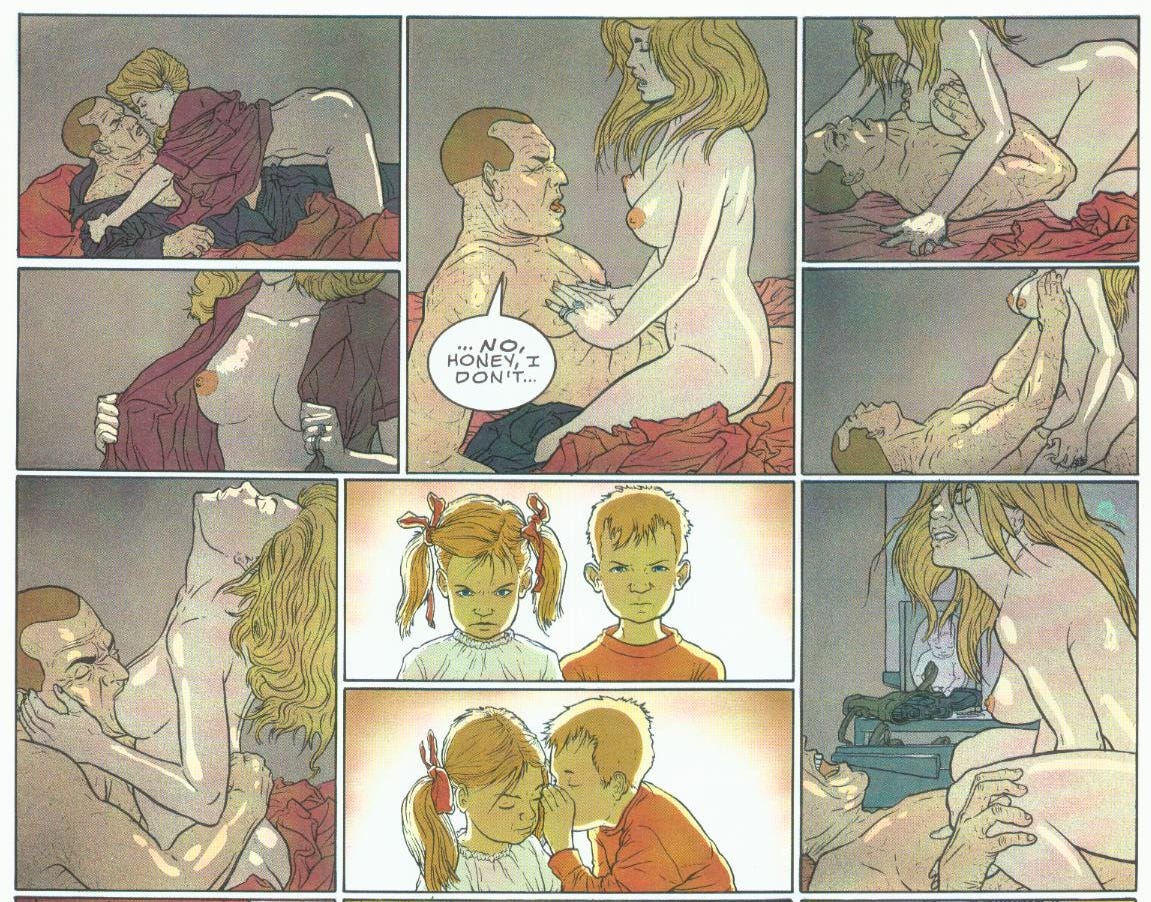

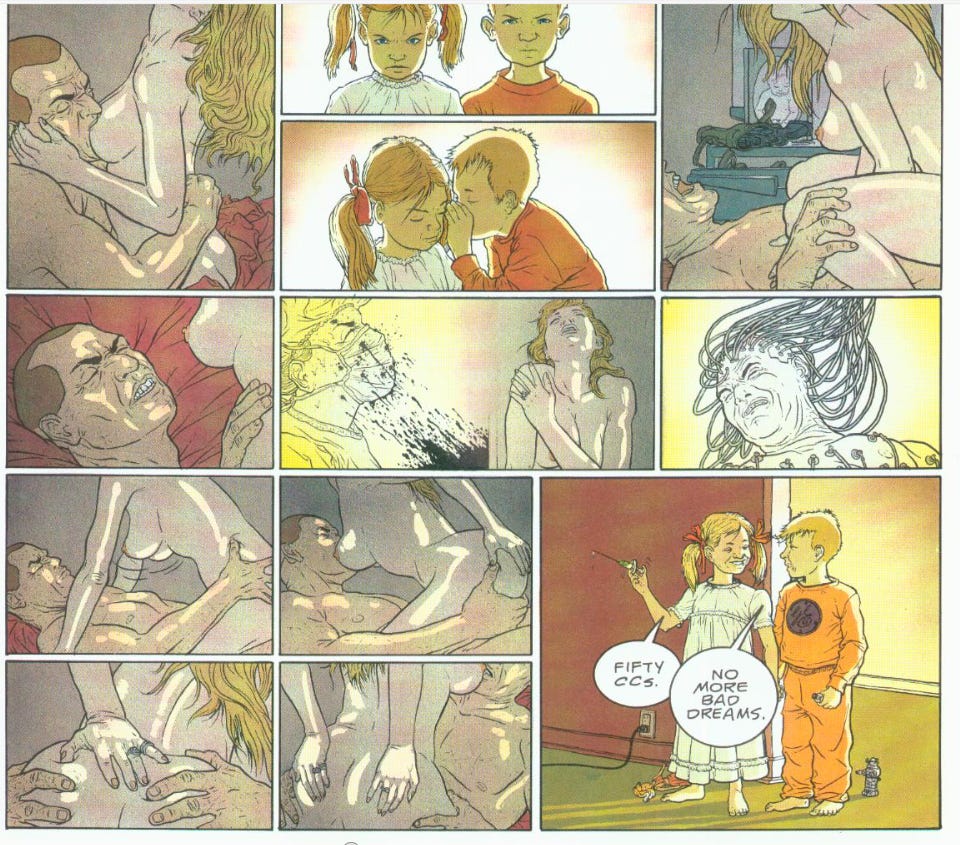

My favorite scene from this series is in Hard-Boiled Issue One, when Nixon returns from a rampage where he slaughtered hundreds of innocent civilians, mostly decimating unfortunate bystanders who happened to find themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time. By the end of this killing spree, his machinery and hydraulics are totally exposed, and the thin veneer of humanity has been peeled back. Operatives from the Benevolent Assurance Corporation race to the scene, then carry him away to mechanics who are dressed like surgeons at a hospital. Repairs begin, conducted in the fashion of intensive surgery at an emergency clinic. His memories are erased, his consciousness is reset. The factory reset is a rough, patchwork job implemented out of desperation. His real memories remain beneath the surface, threatening to emerge once more in a geyser of savage bloodlust.

Nixon goes home like a regular guy at the end of a long day at work.

He tries to sleep.

But his dreams are restless.

Hints of his true nature simmer beneath the surface, threatening to shatter the illusions he craves, threatening the peaceful, happy facade of a bright nuclear family. A life enriched by a devoted wife, and carefree, trusting children.

Nixon’s nuclear family is quite special… a plutonium-bright cover story, enriched by a spherical fissile core.

At any moment, Nixon seems ready to explode.

It’s happened before.

How long can this illusion last?

How long until he plunges into another brutal, implacable rampage?

His wife and kids are worried. They’re a team of robots conspiring against him, manufactured by the same Benevolent Assurance Corporation. And they’re going to do everything in their power to pretend the illusion is real, to gaslight Nixon into believing that he truly is Carl Seltz the insurance investigator… err… Carl Seltz the tax collector… Err… Carl Seltz the ordinary cubicle resident… ERROR… Carl Seltz who is definitely-not-homicidal-today!

Nixon goes home like a regular guy at the end of a long day at work, exhausted and ready to sleep. He has the distinct feeling he’s forgetting something important, and the vague worry bothers him, until he kisses his wife, and the stress dissolves into the background of his thoughts.

He sleeps, uneasily.

Troubled by violent nightmares.

He wakes up, screaming.

The kids are worried. He doesn't wonder how they arrived so fast inside his bedroom, he never asks how children can manage such a rapid response time — whether his children were vigilantly posted outside his room, like soldiers on duty… or prison guards...

He reassures his children. Nothing is wrong.

Nothing at all.

And in the night, he presses his head against the pillows, and tries to sleep. Again.

The nightmares return, worse than before.

But his wife loves him, and she knows how to comfort him, exactly how to distract a stressed husband from the world’s troubles.

This is a darkly hilarious scene. There are three narrative threads, intercutting and weaving together. In combination, they produce a complex, multilayered tapestry. Each aspect of this scene is contributing a different set of emotions, and functions for a separate purpose to advance the main storyline.

Consider the three simultaneous events happening in this scene:

1.) Robot remembers killing spree, before he was repaired and reformatted.

2.) Robot’s wife distracts him with sex.

3.) Robot’s kids silently watch him from the other side of the room. This is the weirdest and most significant part of the scene. It’s very creepy, like something out of a horror movie. Notice their stern, focused expressions — these children are behaving more like adults than kids.

Each of these three elements are juxtaposed against each other — violent memories, romantic sex, and the creepy children.

And at the end of the scene, the robot boy ties his father down, while the robot girl injects him with some kind of syringe-delivered chemical. A sedative.

In a normal scene, Nixon’s sex with his wife would be hot. But having the kids watching their parents ruins the vibe. It’s a surreal aesthetic, emphasizing a mood of situational black comedy. In musical terms, the combination or juxtaposition of these antithetical elements creates jarring dissonance.

Antithesis, or contrast, or juxtaposition — whatever we want to call the highlighting of exaggerated differences — can serve many purposes. Differences are all around us, in every aspect of life, and a careful artist can purposefully spotlight these differences to provoke an astonishing variety of effects. We might implement antithesis in prose, where antonyms are paired together to emphasize an adversarial relationship between two concepts.

For example:

1.)

“I don't know with which weapons World War Three will be fought, but World War Four will be fought with sticks and stones.”

—Albert Einstein

2.)

“A bully will put you in traction but a professional will put you in a pine box — don’t forget that.”

—Clay Martin, Concrete Jungle

3.)

“Marriage is a young man’s disaster and an old man’s comfort.”

—Robert Heinlein, Starship Troopers

4.)

“We wanted flying cars. Instead, we got 140 characters.”

—Peter Thiel

5.)

“Russell Wilson’s very optimistic, everything’s gonna turn out sunshine and rainbows — and right now, it’s turning out incompletions and losses.”

—John Middlekauf

6.)

“I always start writing with a clean piece of paper and a dirty mind.”

—Dennis Patrick

7.)

“Don’t find fault, find a remedy.”

—Henry Ford

8.)

We don't have Space Age problems, we have Stone Age problems."

—Titus Techera

9.)

"Bin Laden is dead, General Motors is alive"

—Barack Obama

10.)

“A healthy man wants a thousand things; a sick man only wants one.”

—Confucius.

11.)

“I can’t fault you for being shortsighted. I hope you won’t fault me for having a long memory.”

—Frank Underwood, House of Cards

12.)

“A good cop can’t sleep at night because he’s missing a piece of the puzzle. And a bad cop can’t sleep because his conscience won’t let him.”

—Hillary Seitz, Insomnia

13.)

“The Lottery in Babylon. Like all men in Babylon, I have been proconsul; like all, a slave.”

—Jorge Luis Borges, The Lottery in Babylon

14.)

“And Cleos Frey?”

“He swears he knew nought of the plot. Who can say? The man is half Lannister, half Frey, and all liar. I put him in Jaime’s old tower cell.”

—George R. R. Martin, A Clash of Kings

15.)

“You are a man… and this world’s smartest man means no more to me than does its smartest termite.”

—Alan Moore, Watchmen: Issue Twelve

16.)

“I was an openhearted ambassador for my country. I was a degenerate scumbag exploiting poor young girls.”

—Delicious Tacos, Philippines Vacation

17.)

“You solve writer’s block by eating shit and being in agony for years. Force yourself to hammer out worse than useless garbage for hours that feel like lifetimes. Every day, until something clicks and you suddenly need it as therapy. Sit there with a demonic inner voice shrieking at your for a decade. And remember: this is a decade of calendar time. In subjective time, one instant of writing feels like years walking dark mazy corridors of third degree burn self-hatred.”

—Delicious Tacos, OkCupid: My Life is Perfect

18.)

“Love is ideal, marriage real.”

—Goethe

19.)

“Fast women and slow horses will ruin your life.”

—Steven Knight, Peaky Blinders

20.)

"This is one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind."

—Neil Armstrong

21.)

“Pain is temporary, film is forever.”

—Peter Jackson

22.)

“Give every man thy ear, but few thy voice.”

–William Shakespeare

23.)

“To err is human; to forgive divine.”

—Alexander Pope

24.)

“We’ll see what happens. That is my first, final, and only decision.”

—Orson Scott Card, Ender’s Game

25.)

“The wildest colts make the best horses."

—Plutarch

The terms antithesis, contrast, and juxtaposition are used interchangeably. Conventional wisdom in its current form is good enough for a superficial exploration of these rhetorical devices, but the conventional wisdom soon collides against stark limitations; misunderstandings; oversights; flagrant errors.

There’s some confusion when we drill deep into this discussion, because all of the words mean the same thing, but their applications demonstrate a near-infinite versatility. I casually shuffle between these words myself, quite frequently, without marking any distinction. Nobody can separate these synonyms, to identify a clear dividing line between what they denote. So let me clarify the point. In each instance, the artist is illustrating a difference between two or more objects, targets, locations, subplots — whatever is being targeted for the purposes of discussion.

The only thing that matters is where we are choosing to apply this focus, to apply this philosophy of magnifying small differences into enormous epiphanies, which can result in drastic effects.

The list of quotations above serves to illustrate how antithesis can pair together adversarial concepts in prose, and play upon semantic differences to communicate a succinct, cogent point.

A different technique, which deserves its own in-depth discussion, is how to contrast a pair of characters in dialogue, or a scene, or a storyline, and to heighten dramatic tension by exploiting their differences… and exaggerating the distance between their personalities. Almost every scene, in any situation, benefits from applying contrast to generate dramatic conflict between characters.

But for the purposes of this discussion (and only this discussion), juxtaposition refers to a structural contrast between the narrative elements of a plot, which are placed together to create an ambient sense of dissonance in the audience.

Let’s reconsider the sex scene from Hard-Boiled, and how three narrative elements interact together on a structural level, in order to advance the storyline.

1.) Robot’s bad dreams — indicates that Nixon’s memories have been suppressed, but not deleted. The surgery was clumsy, and inadequate. This element furthers the main conflict of the story, which is Nixon’s struggle with amnesia, and his troubled identity as a tireless assassin. “Hard-Boiled” centers around Nixon’s individualist conflict with his role as both a prisoner, and a prison guard employed in a commoditized, totalitarian surveillance state. The main dramatic question is: Will Nixon wake up and realize his true identity, his sinister purpose as a corporate weapon? The obvious answer is yes, because otherwise we don’t have a story. If he remains asleep forever, nothing happens. So the next dramatic questions are: How will Nixon wake up? When will Nixon wake up? How much tragedy will happen before he wakes up? What will be the cost, and consequences of him waking up? What will happen when he realizes the truth? Can he escape from the prison of his identity, or is it too late for him to achieve freedom and self-actualization?

2.) Robot distracted by sex with wife — At first, this seems relatively innocuous. Even romantic, and sweet. By itself, the sex with a busty blonde is pretty cute. The dream of a house, a beautiful, obedient, seductive wife, and smart, affectionate, good-looking kids is a universal ambition. A sympathetic fantasy which is aspirational to a mass audience. And here we are presented with the dramatic stakes of Nixon’s moral choice which provides the heart of the narrative — Nixon must choose between Freedom and Slavery, between Truth and (the illusion of) Family. Both moral choices involve a painful tradeoff, an excruciating sacrifice. To be free, Nixon must tear his heart out. To realize actionable knowledge of the surrounding world, and to assert agency upon his own life, Nixon is forced to abandon the illusion of his humanity, and to divorce himself from the woman and children he loves. But if he chooses the path of comfortable self-deception in obedience to tyranny, then he will continue to exist as a brutal enforcer of merciless injustice demanded by the ruling caste of the status quo.

3.) Creepy children watching their parents have sex — This element changes the nature of Nixon’s sex with his wife, because Nixon seems to be unaware the children are standing in the room, but the wife knows she is being observed. From the unspoken context of the wife ignoring the awkward presence of her children, the audience is able to make an inference based on inductive reasoning, and to make the connection that the wife is knowingly collaborating in the conspiracy to gaslight Nixon and to maintain the delusions of his existence as a robot pretending to be a human. From the serious adult expressions on the faces of the children, and based upon their adult dialogue, we also realize that the bodies of the children are piloted with mature intelligence. And their role as pseudochildren is to monitor Nixon, prevent him from understanding his own life, and to report back on their surveillance to the Benevolent Assurance Corporation. Here the audience is given more evidence that a larger conspiracy is monitoring, manipulating, maneuvering, managing, and monopolizing Nixon’s role in society.

All of these elements, these subplots, these narrative layers combine together.

Each element could be its own standalone scene.

But Frank Miller smoothly transitions between these concepts, juggling a dissonant array of storylines. The result is complex. The pace races forward. It’s a beautiful, intricate performance.

Complex scenes cover more ground, they keep the readers guessing, and the combination of text and subtext creates room for the imagination of intelligent, emotionally-invested audience members to run wild. Speculation feeds itself. A simple scene with a single set of elements is self-explanatory. There is nothing to explore. There are no secrets, no mysteries to uncover. But this story is a puzzle, with many layers interacting together, so that the final product has an amazing depth and scope, compressed into a narrow space.

The pilot episode of the television show “Power” features more or less the same kind of scene, without the black comedy element of children watching their parents have sex.

By comparing these similar scenes, which function in similar roles, we can examine how the dissonant juxtaposition of narrative layers interacts with creative friction, to induce an unsettling emotional impact. And to reveal psychological insights into character, which is always the main purpose of compelling drama.

The pilot episode of “Power” starts with a strong, fast series of events. The main character James Saint Patrick, also known as “Ghost”, walks into a nightclub with his wife Tasha. Both are dressed exquisitely. They are a golden couple, reflecting a man with masculine strength, authority, muscles, and wealth — and his sexy, intelligent, passionate wife. Ghost owns the nightclub, and this is the Grand Opening of his new business.

Camera shots pan across the building, surveying a dancing crowd of fashionably dressed models — everyone in the crowd is good-looking. There’s not a single obese person in the room. The men have the dense, thick biceps of experienced weightlifters. The women have the plunging necklines and slim waists of women at the peak of their youth and beauty. The set represents a glamorized fantasy, of sex and wealth and the exhilaration of life in the ascent.

Cameras intercut between characters, following the progression of the party. Everyone is having fun.

One of Ghost’s employees walks up to him, whispers that an offscreen character named “Tommy” wants to see him in the basement of the nightclub.

Ghost steps into an elevator, and enters the Underworld.

He enters Hades.

Because here Ghost crosses the threshold into another life, another identity — his role as the biggest drug dealer in New York.

Television critics treat this TV show with contempt; they think it’s cliche, a watered-down version of every Mafia movie, except with more sex, the pacing of a soap opera, and a black cast. On some level they’re correct. Like so many other gangster films, this franchise is a diluted imitation of the themes and character arc of Michael Corleone — an intelligent gangster who tried to walk away from the family business, who tragically failed to transition his fortune into a legitimate commercial empire.

To transform himself from criminal kingpin, into a merchant prince.

Safe, and respected by the surrounding social order.

This insider criticism has some merits… “Power” is not remotely an intellectual franchise. But it’s been a persistent, top-rated sensation for good reason. It’s fun. And sexy. And violent. It’s a confident, unapologetic power fantasy, at a time when everything else in film, television, and literature is poisoned by neurotic, anticolonialist self-loathing which reflects the perversion and corruption of American decline.

Crime stories reflect American decline in a different sense, that as American patriotism atrophies, and popular belief drifts away from the civic mythology which justifies the status quo, then crime stories take on a new cultural importance. Their fascination in today’s media is a symptom of a defect-defect equilibrium. A symptom of the ethos of a low-trust society, where anyone who plays by the rules is viewed as a sucker. Because the law is for the rich and well-connected. Politicians write legislation for their friends, their donors, their social caste. Rules only serve to keep civilians in their place, as sheep.

Or so people come to believe, as they watch Congressional insider trading go unpunished, while petty laws and penalties are rigorously enforced against ordinary citizens.

Television critics are part of the establishment — ideological allies of the status quo. And it makes sense they would reflexively shy away from this sort of pop-culture, which is both vulgar and shameless.

In the basement, Ghost finds a man who has robbed his criminal network of drug traffickers, and escaped with hundreds of thousands of dollars collected from the day’s sales.

Brutally he interrogates the captured hitman, pulverizing what’s left of the assassin.

Ironically, Ghost’s nightclub is named “Truth”, which is a nice symbol for the complicated double life he’s living. The descent into the basement, Ghost stripping off his cultured suit and tie in order to prevent blood from splattering his nice clothes, and to smash the prisoner’s face open with his bare fists — all of this is excellent visually, dramatically, and thematically. It’s surprisingly elegant, and intelligent, for what’s considered to overall be a very dumb, shallow media franchise.

Exposition is provided between punches.

The robbery on Ghost’s network was too precise, too professional to be anything other than an inside job. James Saint Patrick realizes that he has a traitor on the inside of his operation, a Judas. And that Judas is collaborating with a mysterious hidden enemy on the outside of his gang — probably one of his own business partners, one of the local gangsters he supplies drugs to.

This plants a mystery in the style of an Agatha Christie novel — in later scenes, Ghost and Tommy travel to the various local warlords of New York, which provides the audience with a list of suspects. Perhaps one of these men, all of these men, or none of these men have orchestrated the robbery.

Searching for answers, Ghost realizes he needs his organization to shift to a defensive posture, and to shut down their normal business routine until their mysterious enemy has been identified. Because the attacks on their supply chain will continue.

In the basement, James Saint Patrick murders the captured hitman. But he’s learned nothing.

Later, Ghost is laying in bed after a night of troubled sleep.

Here begins the parallels between Nixon the robot, and Ghost the criminal.

Both men have more or less the same scene play out — passionate sex with their wife, punctuated by sporadic flashbacks to a recent scene of violence and destruction.

Tension gnaws at Ghost. The accumulated problems of an overextended criminal network. He has so many problems: a struggle to retain his anonymity as he grows in wealth and connections… a sophisticated, mysterious nemesis who is deeply familiar with the habits and protocols of his clandestine network… the velocity of cash and drugs trafficked through a system of far-reaching digital surveillance… the burden of managing unhappy, unreliable personnel… and most of all, his desire to walk away from the game.

He’s the man who has everything: the perfect life, the perfect wife, the Patek Philippe watch, the sports car, the bodyguards and drivers, the luxury real estate, and three happy, healthy children.

If crime is a casino, he’s ready to take his winnings and cash out — while he still can. He’s beaten the odds. He has gambled, and won. Now it’s time to quit playing, to quit taking risks.

All of these unspoken stressors are bothering James Saint Patrick.

And he channels that intense tsunami of emotions into sex, pounding his wife from behind. Their sex is angry, and rough. His wife loves it. Between thrusts, he thinks back to the night before with guilt and rage — punching, strangling, slaughtering the captured hitman in the basement of his nightclub “Truth”, on the night of the club’s Grand Opening.

There’s a nice little touch in the cinematography of these flashbacks. The footage is tinted with a dim, subtle gray to signal that it’s a flashback, which is traditional. And the camera angle is from a different perspective than seen earlier, more graphic than before, showing profuse blood-splatter against the cement.

His wife enjoys the morning’s entertainment.

Afterwards, she’s upset when he doesn’t want to cuddle, and hurries away from the bedroom, dressing for a busy day of managing his empire, hunting his enemies, and staying vigilant as everyone around him tries to steal his fortune. Tasha’s pained reaction reveals that she’s insecure about their marriage, and she’s seeking reassurance from her husband. This provides a minor note of foreshadowing, which later in the pilot episode becomes more relevant, when Ghost reconnects with his childhood sweetheart, and explores the possibility of infidelity.

So, having reviewed an extensive summary of the opening events of the pilot episode of “Power”, now we can consider how juxtaposition functions in this sex scene, as violent flashbacks intercut between a panting, gasping crescendo in the present.

To return to musical terms, the sensual marriage scenes and the melodramatic interrogation of a doomed thief — these threads are paired together in a duet. The downbeat memories operate in counterpoint to the present carnal delights, and they reach a climax together. The result is dissonance. Disharmony groans on a fundamental level.

Obviously, Ghost’s mind is elsewhere. He’s distracted from his wife. On a deeper level, he’s haunted by his conscience. And he’s burdened by ongoing concerns — concerns which the audience realizes he doesn’t share with his wife, either because he doesn’t trust her enough to share his crimes, OR because he doesn’t want to incriminate her as an accomplice to numerous felonies, OR because knowledge of the constant dangers of their lifestyle would disrupt her enjoyment of ordinary life.

Either he's trying to protect her, or to protect himself.

James Saint Patrick is an archetypal figure in the mold of The Great Gatsby — he has everything in the world, he has climbed from the poverty and obscurity of the streets to the heights of Manhattan. But he cannot enjoy it, because he is fixated on the nostalgia of the past, and regrets missing out on The One Who Got Away.

Despite his wealth, he dreams of a different life. Perhaps even a different wife.

Juxtaposition adds an intriguing layer to what would otherwise be a tantalizing, but simplistic romantic moment. A penetrating depth, which arrives with sudden force. Much of this complexity is unspoken — none of the characters ever announce their emotions. They talk around their problems, circling each other warily, hesitant with their suspicions.

So again, we return to the robotic assassin Nixon, and compare him in parallel with James Saint Patrick.

Their emotional struggles, their character arcs are the same. More or less. To restate this in more precise analytical terms, their struggles mirror each other as precise opposites; as symmetrical, inverted echoes of the other man.

Both men are warriors trapped in a prison of elegant, elaborate deceptions.

By retiring from crime and transitioning into a legitimate nightclub, expanding his franchises across every major city in America, Ghost is trying to escape into an ordinary life — the sort of domestic serenity which Nixon already enjoys. But Ghost knows what he has, and who he is. As he beats a captured enemy to death beneath the nightclub “Truth”, James Saint Patrick possesses absolute clarity in terms of the surgical violence he is inflicting upon another criminal, and the strategic maneuvers he will adopt to survive. Nixon is trying to realize the truth about himself, but he has the domestic simplicity which Ghost is chasing.

We can thematically juxtapose these characters.

We can imagine a story, a fictional world shared by this pair of iconic, monstrous individuals. Together, they would reflect a certain dualistic exploration of crime and marriage, violence and intimacy, self-knowledge and self-deception. Both would be destroyed, no doubt, because it’s difficult to imagine anything but a tragedy which might feature two monsters of this breed.

But their examples provide a marvelous gateway to storytelling techniques, and a consideration of how to layer together narrative threads.

Peter Gould, The TV Showrunner’s Roadmap to Creating Great Television in an On-Demand World:

“One of the fun things about working on both Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul is that we have very few structural obligations. Beyond act breaks and running time, we can experiment with the format as much as we like. For one thing, that means that our lead actors don’t have to appear in every single episode.

That’s very freeing.

We’ve had episodes where Mike doesn’t show up, episodes without Kim, episodes without Nacho… So far we haven’t done an episode without Jimmy, but it’s not inconceivable. We came very close in “Five-O” – that’s the episode that centers on Mike’s history. We were breaking the story with the idea that we wouldn’t see Jimmy at all and then, pretty late in the game, we had the inspiration for Mike to use Jimmy to obtain the investigating detective’s notes.

But traditionally, if you have actors who are series regulars, you want to see them in every episode. You often see an episode structure that’s sort of a round-robin, where each character gets their turn. You’re cutting between the A story, the B story, the C story, and so on.

On both Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul, we like to think of the whole show as one story. And if we’re cutting between different characters who are up to different things, it’s because those things mean something when juxtaposed together, and sooner or later their actions will all collide.

Having said that, if we’re not going to see a character for a couple of episodes, I generally call the actor to check in and let them know we still love them and we love their character and we’re going to get back to them. Sometimes when people are deprived of information, they fill the void with their own fears and doubts. That kind of communication is part of running a show that you don’t hear about as much, but it’s crucial.”

—Peter Gould, The TV Showrunner’s Roadmap to Creating Great Television in an On-Demand World

When separate layers combine into a gestalt project, the interaction will essentially be either: positive, neutral, negative, or irrelevant.

In other words, the combination of two separate narrative elements has the potential to reinforce, emphasize, amplify, mirror, parallel, echo, critique, undermine, subvert — or do nothing that has any kind of connection with the other parts of the story. Everything has a tradeoff. Any aesthetic decision you commit, will have useful and maladaptive consequences. There is always an upside, and a downside, which impacts any decision.

Because of this compound effect, where tradeoffs build upon tradeoffs in the fashion of a force multiplier, as artists we want to design each of our choices to operate with some level of synergy, or symbiosis, so that the strengths and value propositions of previous decisions are reinforced by every subsequent, cumulative choice which the narrative will accumulate over time. The future cannot be precisely predicted, such a rigid structure would lead to stagnation — but by moving forward with purposeful intention and a vision, we can set ourselves in an intelligent direction. And on some level, we can anticipate the most common shortcomings and flaws of any particular artform, and devise clever solutions to the challenges we expect to confront in a particular medium.

Everything should operate as a unified whole.

When you lay a solid, intelligent foundation based on deep-rooted thematic, aesthetic, or psychological insights, then the story begins from a place of clarity, power, and emotional resonance. Deep truths form the bedrock of the enterprise. There’s a natural consistency embedded in the origins of the work, and when you lose sight of your aesthetic compass, you can reorient yourself by returning to the original vision, and recommitting to the original design principles. If you randomly pick stuff that seems “cool”, and begin a large project with a vague series of arbitrary, haphazard decisions, then it’s possible that intuition will arrange these reflexive choices into some kind of unified whole, and that does sometimes occur, but more often than not, chaos grows into a complex form of entropy and disaster.

This whole essay has been spent on the concept of juxtaposition, of how to utilize a sense of dissonance, inserting absolute wrongness in a masterful fashion. Because if you can do that, you can do anything.

And if you understand why dissonance works, mechanically… you can flip that framework to create multifaceted narrative tapestries which parallel and reinforce and heighten each other, operating in a musical chorus of complementary elements, to produce a symphony that speaks to the audience on a profound level.

Tom Shone, The Nolan Variations:

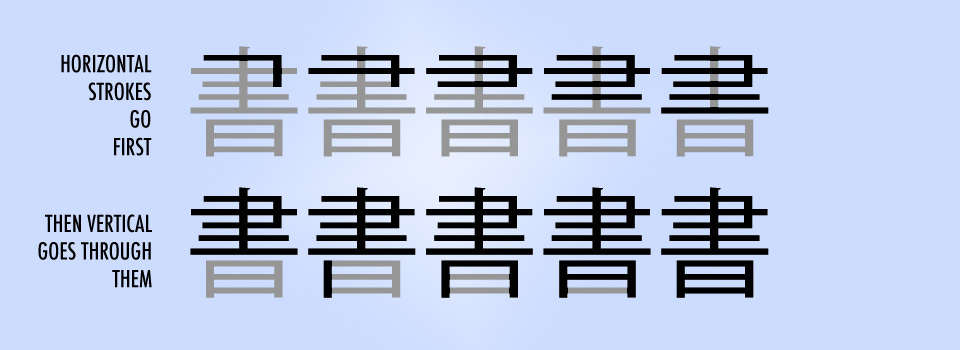

“‘One of my big disappointments in life was to go back and look at the films again and realize how crude they are. Everything I did in filmmaking was a slow evolution. As a kid, it was just about putting interesting images together and getting a narrative to it, because Super 8 was silent, of course. So, unlike kids today, who have sound at their disposal, it was purely an image-making process. I was reading Eisenstein’s book Film Form the other day, and the argument he makes — it’s funny that it would ever have been controversial — but you take shot A and shot B and put them together and that gives you thought C. And that, I realize now, is what I was working out for myself.’

…

The son of a master mason in Riga and trained as an architect and civil engineer at the Institute of Civil Engineering in Saint Petersburg before turning his attention to set design and filmmaking, Eisenstein was cinema’s first great structuralist thinker.

Famously, he compared the art of cinematic montage to Japanese hieroglyphs, where the combination of two hieroglyphs of the simplest series is more than just the sum of its two parts — it creates a third meaning. So if you cut from the shot of a woman with pince-nez to a shot of the same woman with shattered pince-nez and a bleeding eye, as Eisenstein did in Battleship Potemkin (1925), you create a third thing entirely: the impression of a bullet having hit the eye.

…

Natalie, you’ll note, has gone through all the normal developmental stages of a classic femme fatale, from seduction to trust to betrayal. The scenes are in reverse order, but everything else, the rhythms of character and plot development, proceed forward as normal. The universe of Memento may be one of pure, tumbling chaos, but the storytelling is a model of clarity, with Nolan using all the means at his disposal — Leonard’s tattoos, his notes, his voice-over, the sounds that start each scene, the cleanness or unkemptness of Lenny’s clothes, the age of the wounds on his face — to nudge our memory and reassure us that we are on track.

‘The overarching narrative of Memento is incredibly conventional,’ says Nolan. ‘On purpose. The emotion and experience needed to be extremely familiar. One of the films I saw as I was writing it was David Lynch’s Lost Highway. I’m a Lynch fan, but I was left like, What the hell was that? It felt too strange, too long; I almost didn’t finish watching it. And then, about a week later, I remembered the film as if I were remembering one of my own dreams. I realized that Lynch had created the shape of a film that would project a shadow in my memory, assuming the shape of a dream. It’s like a hypercube — the shadow of a four-dimensional object in our three-dimensional world. It’s back to Eisenstein’s shot A plus shot B gives you thought C. That’s the ultimate aspiration of what you want to try and do with the form of a movie. You want to try and create something that isn’t just film running through the projector. I think there are other films like this, Tarkovsky’s Mirror, for example, and Malick’s Tree of Life. And that’s what Memento tried to do in its own way and succeeded in doing, judging by people’s response. The thing I was proudest of is that your experience of the film was not just the film running through the projector. It bled off in all these different ways. It created a three-dimensional narrative.’”

—Tom Shone, The Nolan Variations

So, to reiterate these concepts in simple terms.

Rotating through multiple layers creates complexity, depth, scope. And a story with only one layer is boring. Mysteries fascinate us. Questions haunt us. If everything is exactly what it seems to be at first glance, that’s boring to the audience, but this kind of absolute transparency fails in a more profound respect, which is that an aesthetic of total transparency fails to simulate the uncertainty, unpredictability, and opacity of the real world. Stories are simulations of the actual reality which surrounds us on a daily basis. Verisimilitude lubricates the fantasy. Psychological realism earns trust from an audience. In real life, people almost never tell you the complete truth of who they are — without a fight. Nobody will confess their deepest fears in public, unprompted.

Beneath every rock, there are maggots crawling in the mud.

We can zoom in on the finer details of narrative fiction. Or we can zoom out, to observe how layers accumulate into dense compressions of insight, expressed through delightful drama. Either path should lead us to the same end result. Our sensibility should consider each fragment of the jigsaw puzzle, and carefully design the various pieces to produce their intended effects.

Rafael Alvarez, The Wire: “Truth Be Told”:

“Yet one rule is strictly observed: All of the music has to be ambient, meaning it has to be justified by a source within the scene, either a boom box or a stereo or a car radio or a band belting it out in a bar that doesn’t even have a stage. In keeping with the documentary feel of the drama, The Wire does not score music to suit a mood, with the sole exception being the closing minutes of each season as a montage reveals the outcome of the story character by character (Jesse Winchester doing “Step by Step” at the end of Season One; Earle’s “Feel Alright” closing out the following year).

Until those final moments, all of the music must exist within the reality of the scenes. As reality often dictates — life being the stuff that happens while you’re busy making other plans, according to John Lennon — nothing should perfectly match. “If the lyrics are dead-on with what [the story] is trying to say, it’s redundant,” said Simon. “Instead, we try to speak to mood and tonality, but obliquely, particularly in regard to lyrics.”

Picking a theme song meant walking a finer line, even more so than the fabled Johnny Cash anthem to fidelity that accompanies Detective Pryzbylewski at the top of an episode in Season Two as he arranges photos of targets and their names on a detail-office corkboard. Since the theme song is the handle by which many folks remember their favorite television program — who of a certain age can not whistle the instrumental that opened The Andy Griffith Show — the theme for The Wire had to be both on-and off-target at once. “Songs can be on point, but only up to a point,” said Simon, who deliberated for weeks on a possible theme with coexecutive producer Bob Colesberry. “A lot of different things I listen to are like that, but all of Tom Waits is like that.” Waits — whose three decades of work has spanned a white boy’s homage to Satchmo to music that sounds as if it were made with little but human bones — won Simon’s heart long ago with his writing. “Waits’s songs are never on point but they lend themselves cinematically,” said Simon. “He’s painting pictures in those songs and they’re never linear. At least they haven’t been for a long time.”

—Rafael Alvarez, The Wire: “Truth Be Told”

And the last point is this…

Everything needs a purpose.

Each line of dialogue, each description, each character needs to contribute something to the story. And it must be a unique contribution. If three characters are filling the same role, then two of them are redundant, and should be removed from the story, or merged into a composite archetype, or expanded and differentiated until a trio of unique, individualized personalities has emerged from the monotonous morass of triviality.

Layers can mirror each other. They might parallel. All sorts of interesting commentary can be produced by constructing a dualistic interrogation of a suitable theme. But at some point, the threads must diverge, or converge, or reemerge into bold directions.

Everything needs a purpose.

Stories are fun when they surprise us.

When they distract us. Or delight us.

When they teach us… and when they remind us, of how beautiful life can be.

I love this attention to juxtaposition. Your writing helped me see why juxtaposition of the same character in consecutive panels is also jarring. I noticed the kids are rather serious and almost sinister at first but then soften into childlike innocence as they whisper to each other. I think this back to back framing is what makes films like “Smile” so terrifying. The same face goes from friendly to menacing in a moment. There’s some primal fear there that is heightened by the framing.

Also, the blandness of modern media stems in part from this lack of contrast. Even the villains have understandable backstories that explain away their methods (like Thanos). I love pulp fiction with Solomon Kane and the like because of this deliberate juxtaposition of pure good and pure evil.