“Khrushchev’s increasingly erratic policy decisions put him in low standing amongst the rank and file of the Party, but the new consensus was still against a return to Stalinism. In 1964, a faction of Stalinists under the leadership of former KGB head Alexander Shelepin organized a coup, and Khrushchev was informed of his deposition while vacationing on the Black Sea. But the old guard of the Politburo was able to maneuver in an opponent of Shelepin, Leonid Brezhnev, as a replacement. Brezhnev was agreeable, predictable, and not the type to rock the boat with either radical or reactionary reforms.”

—Alexander Gelland, The Censor who Ended the Soviet Union

https://www.palladiummag.com/2023/01/30/the-censor-that-ended-the-soviet-union/

History spirals, and in its eddies we find strange convergences — hypermodern corporate Disneyland and the ossified machinery of the Soviet Union, each ruled by decaying gods, each primed for ritual sacrifice. Michael Eisner and Nikita Khrushchev: two sovereigns fattened on past victories, hemorrhaging authority in systems that no longer believed their ruler’s myths.

And in their shadows, two smooth operators: Bob Iger and Leonid Brezhnev — avatars not of revolution, but of moderation, correction, stabilization, procedural serenity, and a return to a risk-averse, orthodox consensus.

The ousters of Nikita Khrushchev and Michael Eisner shared a peculiar symmetry, a ballet of power where courtiers grew weary of kings who had overstayed their welcome.

The dispute centered on tactics and style, rather than any kind of ideological gulf.

In each case, a brash, hot-tempered leader was deposed by his understated, urbane protege.

By the 1960s, Khrushchev ruled with the unpredictability of a thunderstorm. His vision for the Soviet Union had once dazzled — de-Stalinization, the space race, the gamble of the Virgin Lands — but soon it teetered on farce. Nikita Khrushchev tore down icons, without building new structures in their place. He humiliated his ministers, toyed with vast reform, and lacked a clear direction with consistent, disciplined execution. His speeches, impassioned and unpredictable, were eruptions from a decaying empire. Military brass winced as he slashed their budgets. Party elites shuffled uneasily as policies flipped overnight. Top bureaucrats were promoted and demoted at irregular intervals, causing unease among the men who should’ve been his most enthusiastic loyalists. In the aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Khrushchev was a diminished figure.

Brezhnev, his protege, a man of gray suits and quieter ambitions, listened, nodded, and waited.

Flash forward to Disney, early 2000s. The Magic Kingdom was losing its magic. Michael Eisner, once the alchemist of the modern Disney renaissance, had soured into a corporate autocrat. He stopped being a visionary and started being a liability. Eisner ruled with his fists clenched around the reins — brilliant ideas undermined by scorched-earth grudges, broken partnerships, and an inflated sense of vanity. Artistic partners fled. Tense creative disputes escalated into full-fledged corporate warfare, as Michael Eisner feuded with Steve Jobs and Pixar. Shareholder confidence eroded. The corporate body rejected him like an immune response to an autoimmune disorder. Roy Disney (Walt Disney’s nephew) quit in protest, calling Eisner’s leadership arrogant.

In the wings stood Bob Iger, calm, composed, the kind of man who made spreadsheets sing. A man of subtlety and courtesy, wearing patience like armor. He didn’t rebel. He listened. He observed. He charmed, smiled, and soothed.

Bloodless coups ambushed Khruschev and Eisner.

By the time each wounded, besieged dictator stepped down, it felt inevitable, as the volcanic tempers of Khruschev and Eisner surrendered to a boardroom mutiny that unfolded behind the scenes, allowing each tyrant to accept his banishment with a pretense of dignity.

Fait accompli.

The institutions reasserted themselves.

Avatars of inertia were promoted in their stead, as Bob Iger and Leonid Brezhnev were promoted to play the role of a quiet frontman representing a vast institutional consensus.

Each figure was picked so that the machine would be allowed to run itself.

When the time came, both successors wore the mask of necessity. Brezhnev offered predictability to weary Soviets. Iger offered competence to wounded shareholders. Neither shouted; they simply stepped forward when the incumbent tyrant had exhausted the tolerance of his subordinates.

Both Iger and Brezhnev operated as negative feedback loops — systems self-regulating through removal of chaotic energy. A return to normal. Business as usual. Respect for stakeholders, and an end to volatility. Authority flowed to them not because they seized it, but because the systems themselves, craving equilibrium, selected them.

Each man functioned as the custodian of a slow, grinding consensus.

These velvet coups exiled leaders who had alienated their own base: strongmen punished for being loud, in a world that rewards whispers.

Neither Brezhnev nor Bob Iger was a revolutionary. They were systemic antibodies. Their genius, if you can call self-effacing modesty such an insight, was in knowing that the machine doesn’t need a king. Systems desire predictability, stability, the ability for stakeholders to pursue their own ambitions and manage their own siloed fiefdoms according to tradition.

Order replaced chaos.

And yet… that order had its limitations. None of the troubled company’s fundamentals had changed. The colorful rage and brashness of Eisner, and Khrushchev, distracted from underlying structural flaws.

The problem with institutional consensus is that systemic inertia is incapable of introspection and critical self-examination.

It can’t fix itself.

Bob Iger and Leonid Brezhnev, separated by oceans, centuries, and systems, shared one curious trait: neither really steered the ship. They inherited institutions too big to fail — Disney and the Soviet Union — already gliding on vast currents of momentum. And like men hired to sit in the captain’s chair mostly to reassure the passengers, they did precisely that. Their genius was consensus. Their failure was the same.

Iger’s leadership, like Brezhnev’s, was characterized by deference to institutions, and an almost pathological aversion to conflict with entrenched interests. Where their predecessors were unpredictable firebrands, Iger and Brezhnev were calm, diplomatic, and unwilling to rock the boat.

Imagine a vast, gleaming ship… steel cutting clean through the fog, orchestra playing, champagne glasses clinking. Now imagine no one at the helm. That’s the story of Bob Iger and Leonid Brezhnev: two men commanding titanic vessels not with force, but with the quiet confidence of engineers who believed the machine could steer itself.

Consensus without direction becomes an alibi for decline.

Their leadership, cloaked in the elegant robe of dignity and protocol, was in truth a quiet surrender to inertia. They governed not by fire but by fog, drifting toward disaster on ships they refused to steer.

Movement without mastery is drift, and drift leads to ruin.

Both men were selected not for their vision, but their restraint. And in their deference, the institutions they led sailed straight for the icebergs.

Brezhnev lulled the Soviet machine to sleep, whispering sweet nothings to a bureaucratic corpse. The politburo ossified. Corruption spread like mold in a locked cellar. He watched it all and nodded along, too afraid to scrape away the rot.

Leonid Brezhnev did not so much lead the Soviet Union as preside over its slow-motion decay. His leadership style, if it can be called that, was less a guiding hand and more a shrugging acceptance of institutional gravity. Where his predecessor, Nikita Khrushchev, had stormed through the Kremlin like a rampaging, adrenaline-injected grizzly bear, swinging at sacred cows and rearranging the furniture mid-sentence, Brezhnev was the political equivalent of a sedative. He governed by passive deliberation… less out of democratic impulse than a completely justified fear that attempting to fix anything might cause the whole rickety structure to collapse.

What mistakes did he allow? Nearly all of them.

He permitted a vast, corrupt patronage system to metastasize within the Party. He watched as the economy, built for tanks and tractors, failed to put food on shelves. When scientists cried for reform and generals warned of decay, he blinked and signed decrees that changed nothing. The invasion of Afghanistan was greenlit by inertia, a grim obligation to maintain appearances, tethered to prestige.

Brezhnev’s Soviet Union was a machine no one wanted to fix. Slowly rotting. The military, Party, and KGB became baronies, little kingdoms carved out by men who understood that Brezhnev was not a threat but a shield. He did not dismantle them. He did not disturb them. He let them thicken like blood clots in the veins of the state.

Corruption festered, then bloomed.

Afghanistan was the fatal wound. Not a bold move, but a bureaucratic nod. A war without strategy, fought for appearances.

The same pattern of institutional complacency developed at Bob Iger’s Disney.

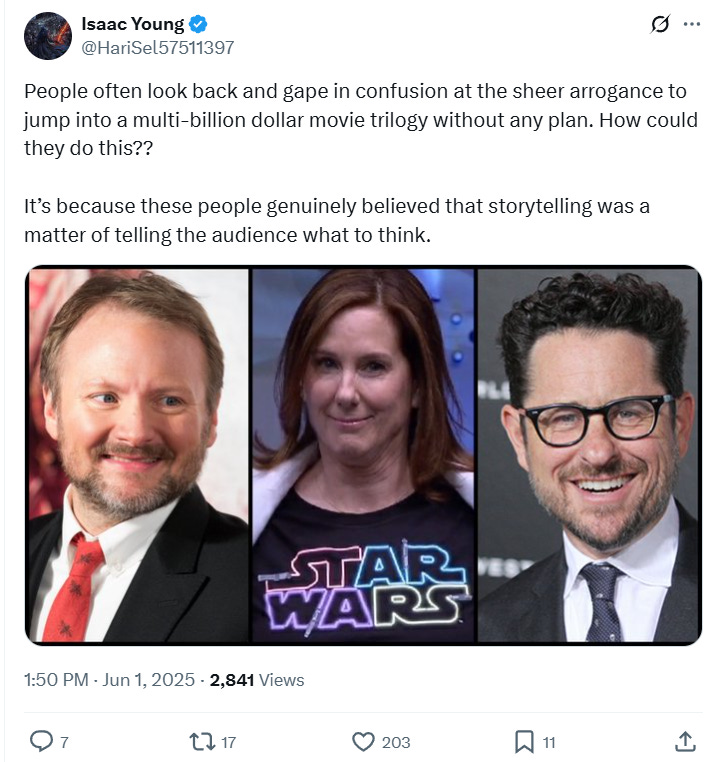

Under Iger, Disney pursued endless acquisitions — Marvel, Lucasfilm, 21st Century Fox — expanding like an empire too large to govern. Disney executed on a strategy of purchasing other people’s proven creative intellectual property (IP), because their own studios had atrophied, and no amount of money could compensate for a lack of imagination.

Creative risk was replaced with spreadsheets. Fear of offending entrenched factions inside and outside the company led to a soft censorship. Disney’s managers suppressed, second-guessed, and micromanaged their artists.

Wokeness was a self-defeating phenomenon.

Disney fell into the trap of purchasing masculine, heroic multimedia franchises that appealed to young boys, then diluting these stories into effeminate Woke slop that featured (but didn’t appeal to) young girls. Internally, Bob Iger allowed a culture of timidity and corporate groupthink to take root. The creative heart of Disney dimmed, dulled by cliche formulas and the anxiety of fractious, internecine corporate politics among a team of rivals. When trouble came in the form of mutinous personnel, political backlash, Woke ideological contamination, and a technological transition to streaming platforms competing for market share in a new media frontier, Bob Iger returned (without solutions) as a nostalgic placeholder for a fading golden age.

The stock price improved. But the product remained the same.

Where Eisner and Khrushchev scorched the earth to plant new seeds, Iger and Brezhnev cultivated rose gardens atop fault lines. They managed decline with grace, mistaking consensus for strength. And like the Titanic’s officers, they trusted the grandeur of the vessel over the warnings of ice ahead.

Neither Brezhnev nor Iger had the appetite for confrontation. They had built ships too large to steer and too comfortable to leave. As warning bells rang, they trusted the ship would glide through. It didn’t.

Stability is not always a virtue. Sometimes, it is the mask worn by decline.

“Brezhnev brought stability to a USSR ravaged by internal contradictions, but the last years of his life saw failure in the Afghanistan War, unchecked declines in party discipline that led to corruption, and the entrenchment of military and industrial lobby groups that prevented reform. By this point, failures in Soviet agricultural policy saw the country importing grain from the United States to sustain itself, and while the USSR was scientifically advanced, it failed to implement technological innovations outside of heavy industry or military contexts. It patched the hole of economic stagnation by increasing commodity exports, but this only enabled further complacency among the nomenklatura.”

—Alexander Gelland, The Censor who Ended the Soviet Union

https://www.palladiummag.com/2023/01/30/the-censor-that-ended-the-soviet-union/

Comparing the late-stage USSR with today's Disney made me chuckle. It is an unexpected but a good comparison. And as everyone will realize, the same thing is happening on a scale in pretty much all Western states, governments, institutions, and corporations. Calcified systems that are no longer capable of fundamental change and that race ever forward purely on inertia, like a burning train without brakes.

Kudos on the comparison between Soviet State Bureaucracy and Cronyism. Two sides of the same she- I mean coin. Hehe 😉👍 Keep up the great work. Peace ✌🏻